How Trump’s FCC shaped the space business for years to come

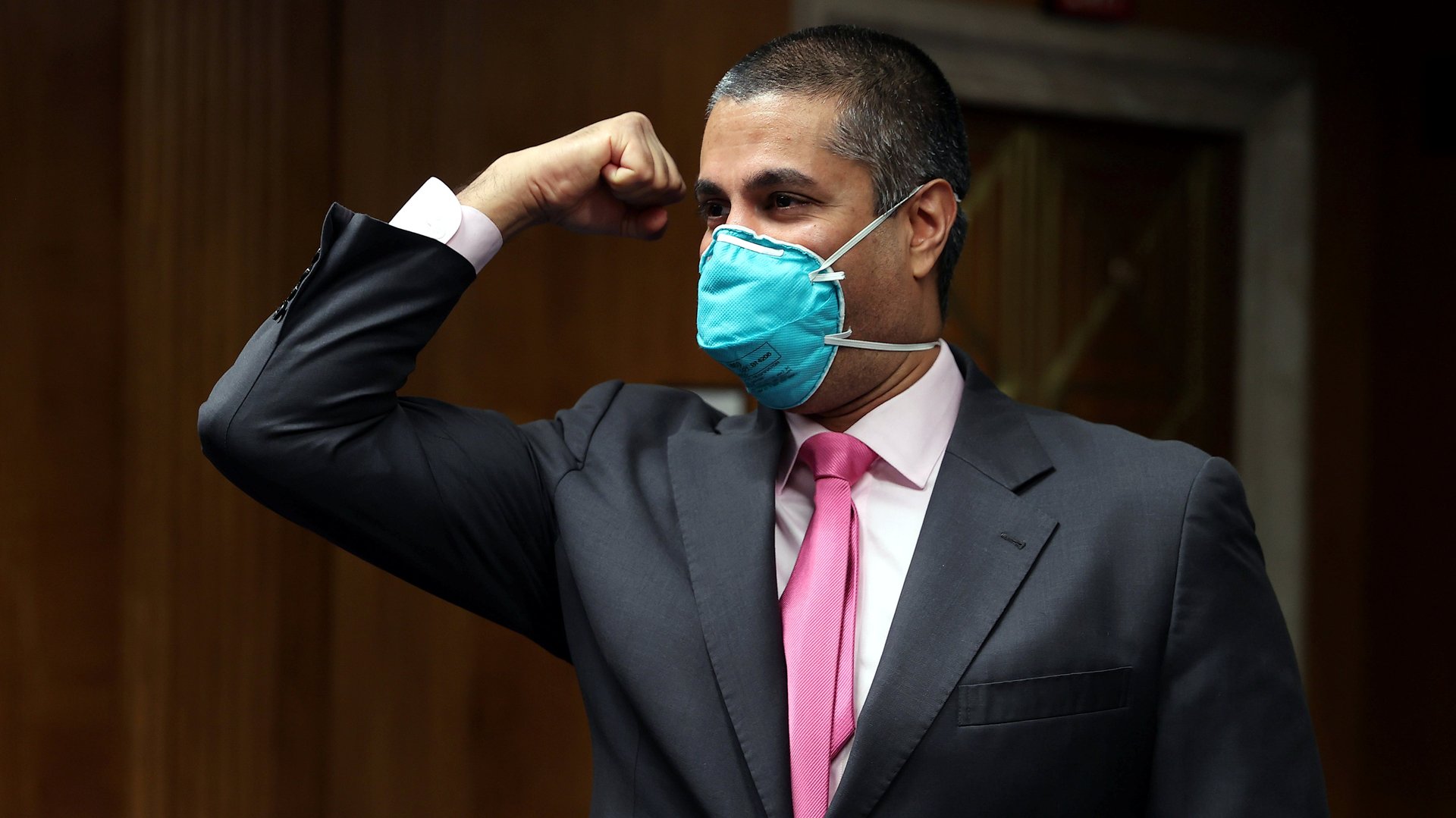

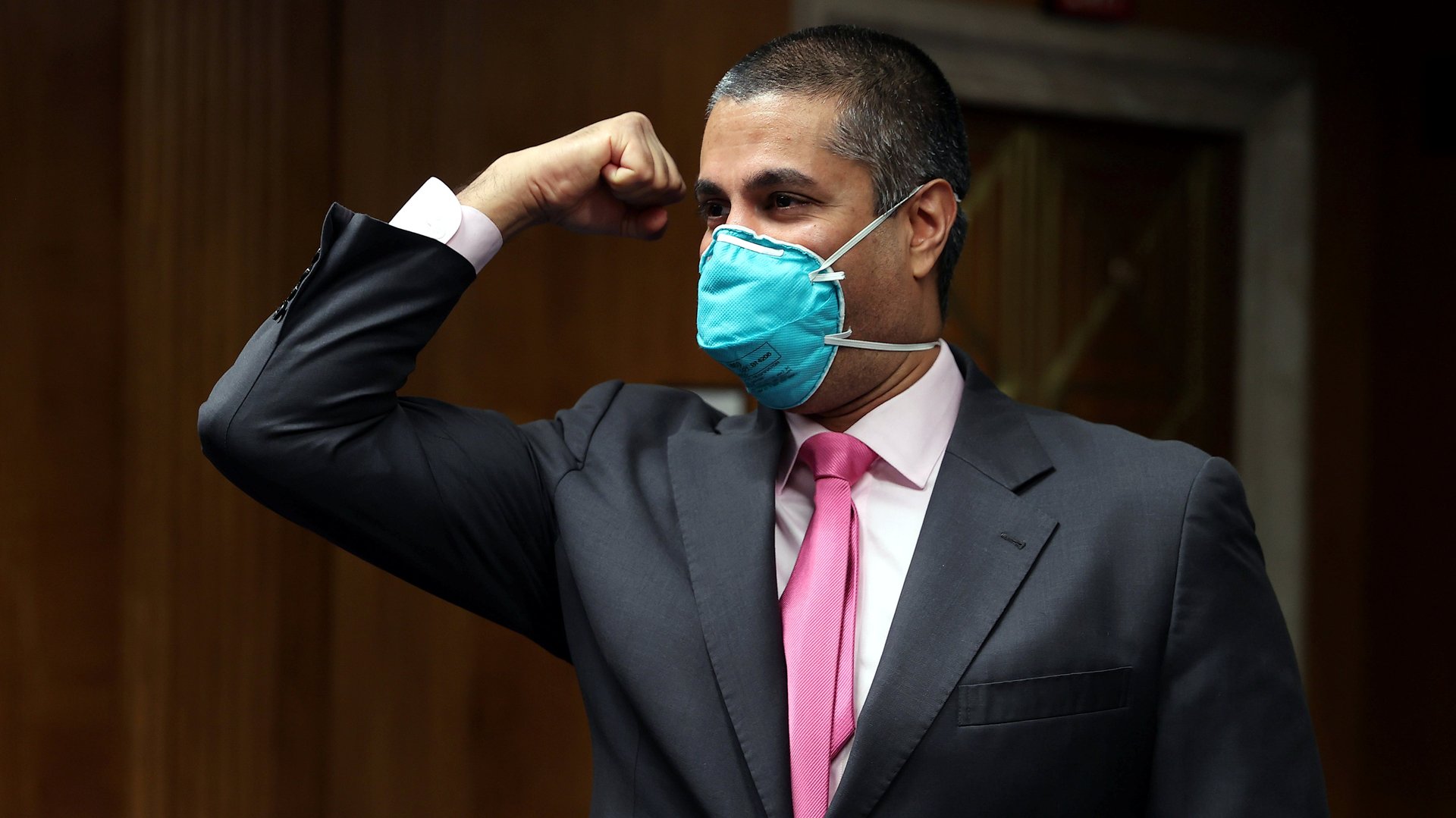

The most important player in recent US space policy wasn’t at yesterday’s uneventful National Space Council meeting. The Federal Communications Commission and its outgoing chair, Ajit Pai, aren’t even members, since the FCC is an independent regulatory agency.

The most important player in recent US space policy wasn’t at yesterday’s uneventful National Space Council meeting. The Federal Communications Commission and its outgoing chair, Ajit Pai, aren’t even members, since the FCC is an independent regulatory agency.

But in the last four years under Pai’s leadership, the FCC has dramatically shaped the future of space commerce: It approved tens of thousands of new US satellites. It prioritized the business use of satellite spectrum over interference complaints from the US military. And just this week, it awarded $885 million dollars in federal subsidies to SpaceX’s Starlink satellite network.

The last news is a result of the Rural Digital Opportunity Fund, a program designed to subsidize businesses that provide broadband in rural areas. US telecom providers participated in a reverse auction across numerous geographic areas, offering the lowest bids necessary to provide high-speed internet access. SpaceX’s monetary award, for service across 35 states, was the fourth largest to emerge from the auction.

Now, SpaceX will have to prove it can provide competitive service in order to obtain annual payments over the next decade. SpaceX did not respond to questions about winning almost a billion dollars in public support; meanwhile, in an interview this week CEO Elon Musk called for the government to “get out of the way” of innovators.

In reality, Musk’s work has been backed implicitly or explicitly by the US government, from his days as web 1.0 entrepreneur as the internet was commercialized; to the founding of his electric car company Tesla with the benefit of green tax credits and federal loans; and through the success of SpaceX, which receives billions of dollars from its primary customer, the US government. Musk has been attacked by ideologues for the reliance of his various firms on such support, but high-tech innovation since the dawn of the aviation industry has done so.

When it comes to rural connectivity, the challenge has been getting companies to do the expensive work of running wires in areas that aren’t densely populated, and thus provide less financial return on the investment. That has resulted in poor service in many rural areas, with impact on everything from jobs and education to health.

SpaceX is not in the burying-fiber-optic-cable business. But Starlink, its growing network of satellites in low-earth orbit, is starting to provide high-speed broadband to a group of pilot customers. The network’s business model is focused on less-dense areas because its system operates more efficiently without tall buildings or too many customers in one spot. That logic led SpaceX to bid for this government backing. Some rivals cried foul, noting that the technology and business model behind Starlink is largely unproven. In the end, the FCC disagreed.

“To the extent that there was criticism out there about whether this could be a real broadband alternative for fixed applications, just being able to bid in those categories is a vote of confidence—a bit of a validation that the LEO service that they are planning can offer what the government itself considers to be broadband,” Walter Piecyk, a telecoms analyst at LightShed Partners, told Quartz.

When it comes to Starlink itself, the news may ease questions about whether SpaceX can afford to deploy the capital-intensive network. Some in the telecom industry suspect that the company is losing money on every antennae its customers purchase, and the new funds could help cover those costs. Still, Piecyk, the telecom analyst, says these economics are not a big surprise.

“Motorola used to make $1,200 cell phones,” he says, recalling the early days of mobile. “It’s hard to judge the ability of a company to get the [customer equipment] to a target price based on the current knowledge of how these products are made today. It’s a great validation, but it’s not like these dollars alone is what’s going to drive the success of Starlink.”

The real big picture will come in the years ahead, when experts say the public will be able to see if the Opportunity Fund met its goals. “If this [subsidy program] works, it changes future planning dynamics,” Piecyk told Quartz. The demand for improved internet access continues to rise. Some people, like former FCC chair Tom Wheeler, have argued that the government needs to spend even more, on the order of $80 billion, to expand terrestrial broadband.

If Starlink—and forthcoming networks built by Amazon, OneWeb, and other firms—prove to be effective competitors, it will change the conversation about how the government boosts internet access.

A version of this story was originally published in Quartz’s Space Business newsletter.