Now, Americans can give money to as many politicians as they want

If there’s anything Americans love, it’s money in politics.

If there’s anything Americans love, it’s money in politics.

(They probably wouldn’t admit it, but revealed preference—like the $7 billion spent on the 2012 federal elections—suggests as much.)

Now, the US Supreme Court has decided (pdf) to eliminate the aggregate cap on contributions to political candidates and parties. Currently, donors can give $2,600 per candidate, to a maximum of 18 candidates, and additional $75,000 to party committees and traditional political action committees, for a maximum spend of $123,200 in each two-year election cycle. Now, unless US lawmakers change the statute—unlikely, since they all benefit from it—there are no limits on the number of candidates a donor may contribute money, and perhaps more importantly, it will allow party committees to raise significantly larger sums from donors.

The ostensible justification for this is that political spending is speech, and the First Amendment guarantees guarantees free (as in unrestricted) speech. More pragmatically, the court appears to be taking the logical next step after its last major campaign finance decision, Citizens United, which allowed independent political groups (so-called Super PACs) to spend unlimited amounts on ads in support of political candidates as long as they don’t “coordinate” with them, a rule more honored in the breach than in observance. Still, it didn’t make sense to the majority of the court that a donor could spend as much as she wanted supporting candidates indirectly but give only $48,000 to them directly.

Campaign finance reform advocates fear this will give the wealthy even more influence in the US political system and make politicians spend even more time spent courting rich donors, especially at a time of rising economic inequality.

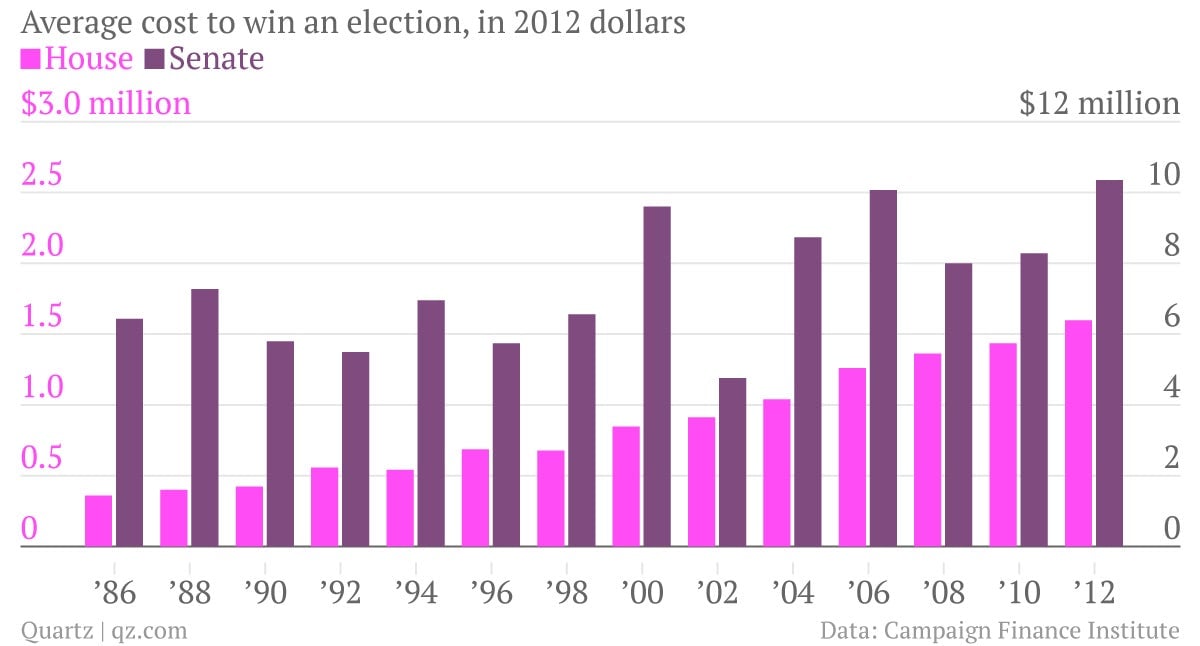

For an example, the Koch brothers, billionaire industrialists who are among the most active political donors in the United States, raised some $407 million during the 2012 election. Now, rather than just spend such sums on independent advertising, they can also donate significantly more directly to candidates and parties. The average winning senate campaign spent just over $10 million in the last cycle; with only 36 senate seats are contested this year, you can bet the 2014 figure is going to be higher.

The conventional wisdom is that Republicans will benefit more from this ruling than Democrats, since they are more popular with wealthy voters and the business lobby.

But predicting the results of campaign finance rules can be a mug’s game. The Citizens United ruling meant an additional $850 million was spent in 2012 compared to the previous presidential election, but the main targets against whom the money was spent—president Obama and vulnerable Democratic senators—managed to win, in part thanks to spending by their own unfettered allies using the same change in rules.

In setting the stage for today’s decision, however, its impact may turn out to be much greater, because today’s decision embraces the logic its critics feared: That it will dismantle the entire structure of campaign finance regulation put in place since the campaign finance scandals of the 1970s.