2020 is the year when the public learned how vital design is for survival

In January, my dental hygienist brought up architecture out of the blue. “How does a building work?” she asked, breaking from our usual small talk about the weather and midtown traffic. This was back when the idea that the strange virus in China might infect the entire planet seemed like a remote possibility. She was particularly curious about the engineering of the two hospitals that rose in Wuhan in a matter of days—a feat that millions followed on YouTube like reality TV. I smiled at the prospect of non-design practitioners nerding over the minutia of pre-fab construction, structural engineering, and ventilation.

In January, my dental hygienist brought up architecture out of the blue. “How does a building work?” she asked, breaking from our usual small talk about the weather and midtown traffic. This was back when the idea that the strange virus in China might infect the entire planet seemed like a remote possibility. She was particularly curious about the engineering of the two hospitals that rose in Wuhan in a matter of days—a feat that millions followed on YouTube like reality TV. I smiled at the prospect of non-design practitioners nerding over the minutia of pre-fab construction, structural engineering, and ventilation.

In a very strange way, 2020 has been a banner year for design. At no other time have we witnessed how much the built environment has a direct bearing on our health and well-being. It’s a rare moment when the general public is scrutinizing the systems behind products and structures.

Little did we know then that Wuhan’s architectural achievement would be a preview for the kind of herculean collective effort needed to defeat Covid-19. With the chain of new problems the pandemic brought, many in lockdown responded by throwing themselves in a hands-on design bootcamp—from making PPE to reconfiguring spaces to arrest virus transmission. In 2020, designing wasn’t about styling or embellishment but about coming up with down and dirty solutions. Thinking creatively and collaboratively became a survival skill.

As the coronavirus infection rates spiked, it was heartening to see hospital systems partnering with architects on building well-thought-out triage centers and isolation wards. The architecture firm MASS Design was among the first to publish free resources on constructing spaces that limit virus transmission. In an op-ed for the Boston Globe, executive director Michael Murphy outlined how the pandemic has brought the guts of oft-ignored, seamless systems to the forefront. “Architecture has been relegated as a passive backdrop, but if it is deployed as an active agent in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic, we can recapture trust over our public spaces and solve problems,” he observed. “The spatial choices we make today, during this emergency, might make or break our ability to survive both this crisis and the next one.”

Making face masks became an urgent pursuit early in the pandemic. Faced with a global shortage, many people dusted off their sewing skills and did their best to make face coverings from found textiles and patterns found online. From the basic pleated design patterned after surgical masks emerged models with improved fit and efficacy. There are even accessible face coverings fashioned for the deaf and hard of hearing. As my former colleague Patrick deHahn underscores, traditional masks don’t work for 5% of the world’s population because those who rely on sign language still need facial expressions for context and people wearing hearing aids rely on lip-reading. A record of these various efforts is on Etsy, where makers of all caliber have sold 24 million face masks as of September. Now designers like Tosin Oshinowo and Chrissa Amuah have even reinterpreted the utilitarian device into esoteric headpieces shown recently at Design Miami. The evolution of homemade face masks is product development on warp speed—an industrial design course in action.

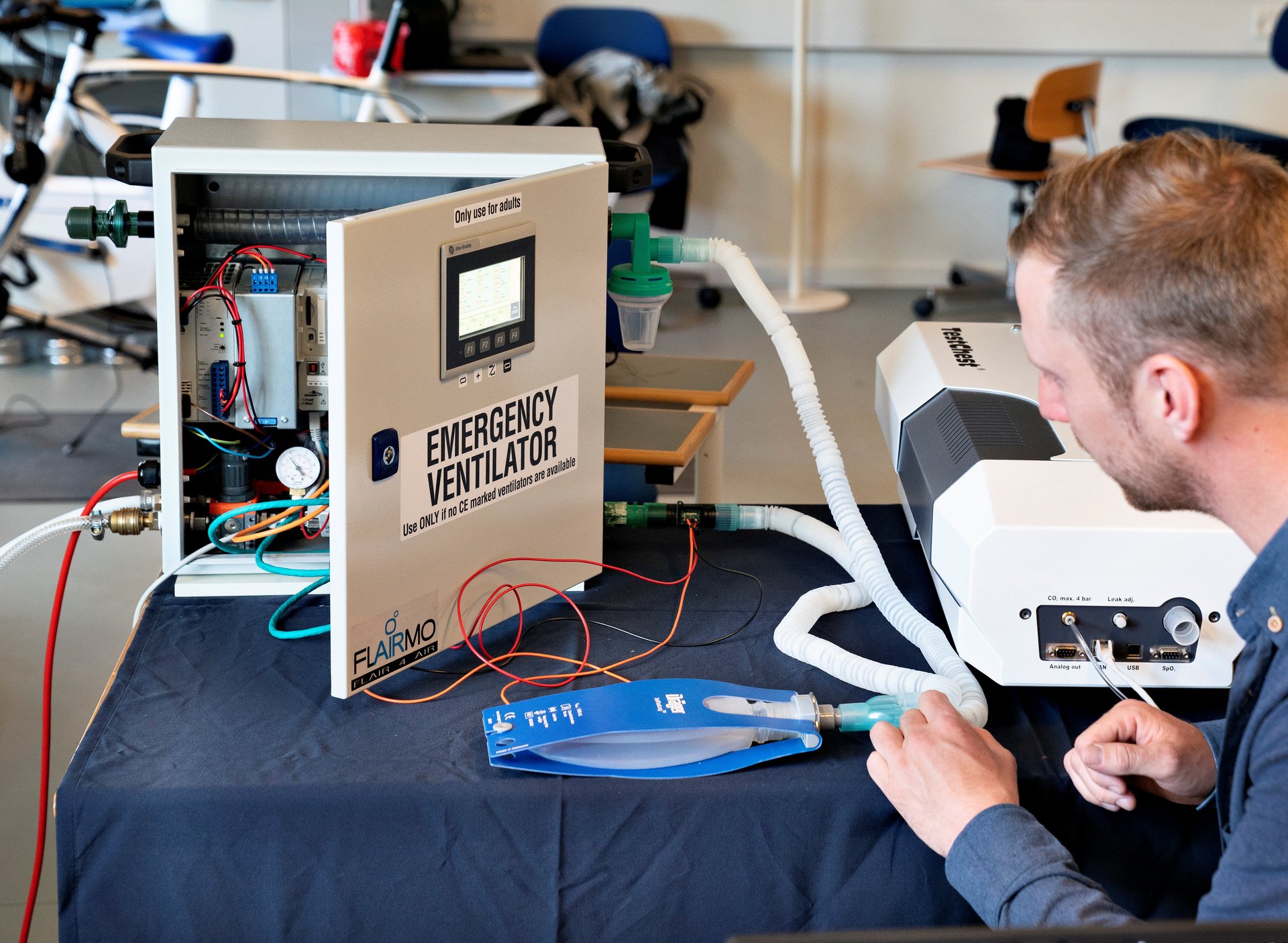

The same can be said about the race to multiply the world’s supply of ventilators and artificial respirators. Teams of doctors from Italy, US, and Australia found ways to split a single ventilator to serve two patients. Ford, GE, and 3M repurposed stock car parts to produce more efficient models within a fraction of the typical product development and approval cycles. Many student groups from Chile, Denmark, Iran, and the US took on the challenge of building medical machines from easily available parts. One notable example: “Afghan Dreamers,” an all-girl team of teen robotics enthusiasts from Afghanistan built a low-cost, manual ventilator with stock parts from old Toyota Corollas and blueprints from MIT. Their prototype costs about $500, which is a tenth of the price of a typical model, to produce.

This year, in fact, has been a heyday for hackers. “We’re dealing with a truly terrifying situation,” explained British design critic Alice Rawsthorn in Design Emergency, an Instagram platform she co-founded with MoMa senior curator Paola Antonelli at the height of Covid-19. “Any response to this tragedy needs to be as fast, efficient, and economical as possible, and hacking tends to deliver on all those criteria.”

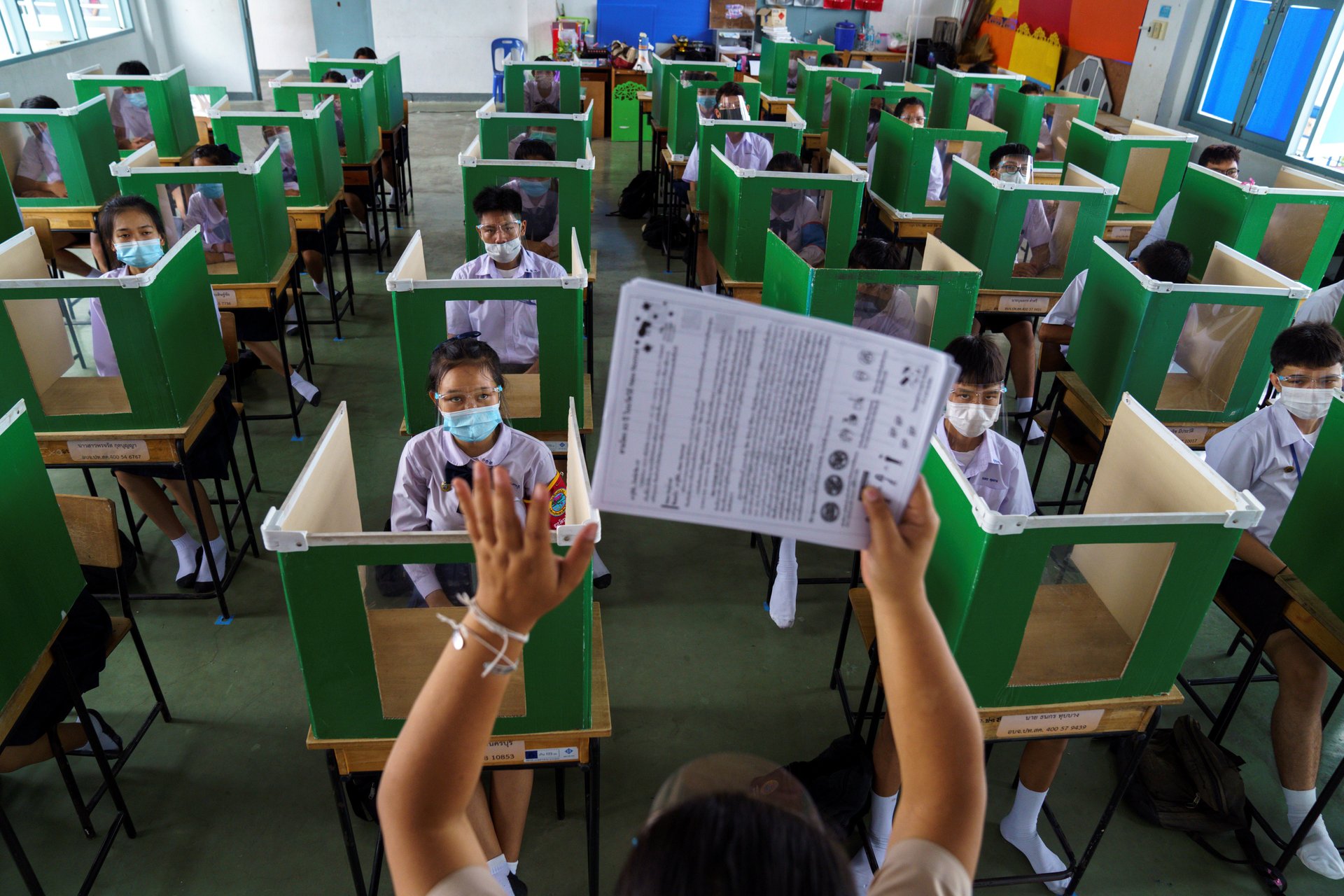

Communicating social distancing information too became a mass graphic design assignment. From simple directional signage to creative uses of masking tape, giant teddy bears, and cardboard cutouts, there are countless clever and often amusing examples of how to convince people to keep a safe distance.

The coronavirus has also made us rethink the design of our streets and public areas. Thoroughfares, once dedicated to vehicular traffic, have been reconfigured for al fresco dining, pop-up parklets, and options for safe recreation.

With cold temperatures in the western hemisphere, restauranteurs are thinking creatively how to stay in business while keeping their staff and customers safe. The same improvisational impulse that produced face masks and ingenious social distancing markers, resulted in a growing array of dining pods. In New York City for instance, the winter “streeteatery” scene is thriving, with painted plywood platforms, Buckminster Fuller-inspired domes, modified garden sheds, and tiki huts festooned with heat lamps.

Our living and working spaces are in the throes of a radical rethink too. With the reality of remote work and home schooling, many are experimenting with ways to improve their set-up. Interior design that promotes physical and mental health has become a leading public concern.

Lessons from Black Lives Matter

Covid-19 wasn’t the only design teacher this year. The Black Lives Matter movement, ignited by the killing of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, led to an audit of the many ways systemic racism is hardwired into everyday systems and emblems that we’ve come to take for granted. It’s in smart phone apps, healthcare algorithms, hiring procedures, dating sites, flags, and civic monuments. The removal of some 30 prominent confederate statutes and the redesign of the incendiary Mississippi state flag this year are reminders that seemingly permanent structures can, and need to be routinely scrutinized and reinvented.

Black Lives Matter has also caused an upheaval within professional design circles. I can’t remember the last time AIGA, the largest professional organization for design, asked its members not to create posters. Instead of making pretty graphics and catchy campaign slogans as it tends to do, its New York chapter offered resources and asked members to act within their organizations to fight racism. The true work of design isn’t symbolic, abstract, or decorative. It’s rooted in grappling with specific problems and its consequences.

The history of design is littered with many quotable manifestos on how it can be a powerful tool for improving lives. But never before have we had such a crisis that showed us exactly how it can be done. If the calamity sandwich that is 2020 has one design lesson to impart, may it rid us of the notion that design is just about style and aesthetics.