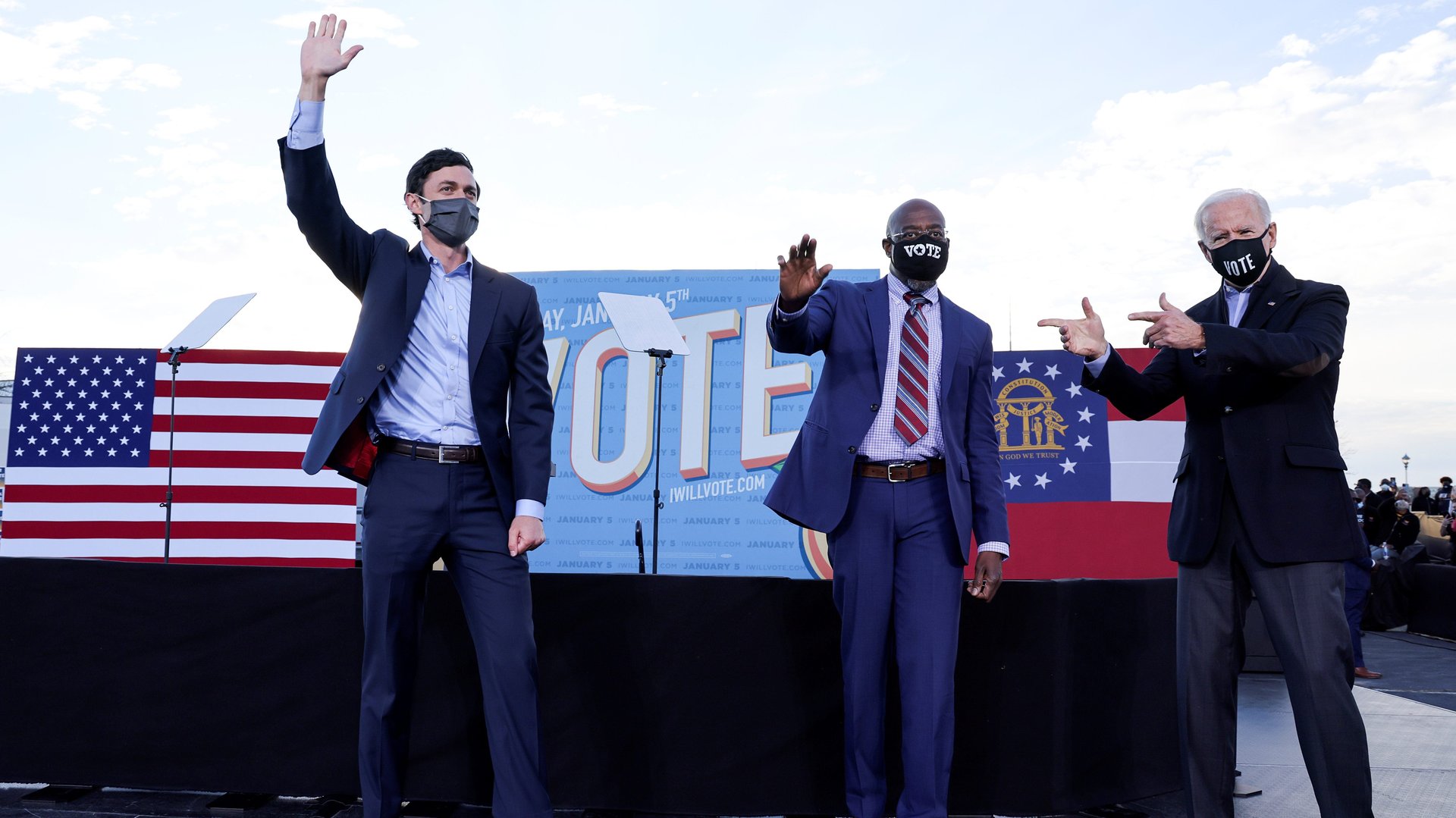

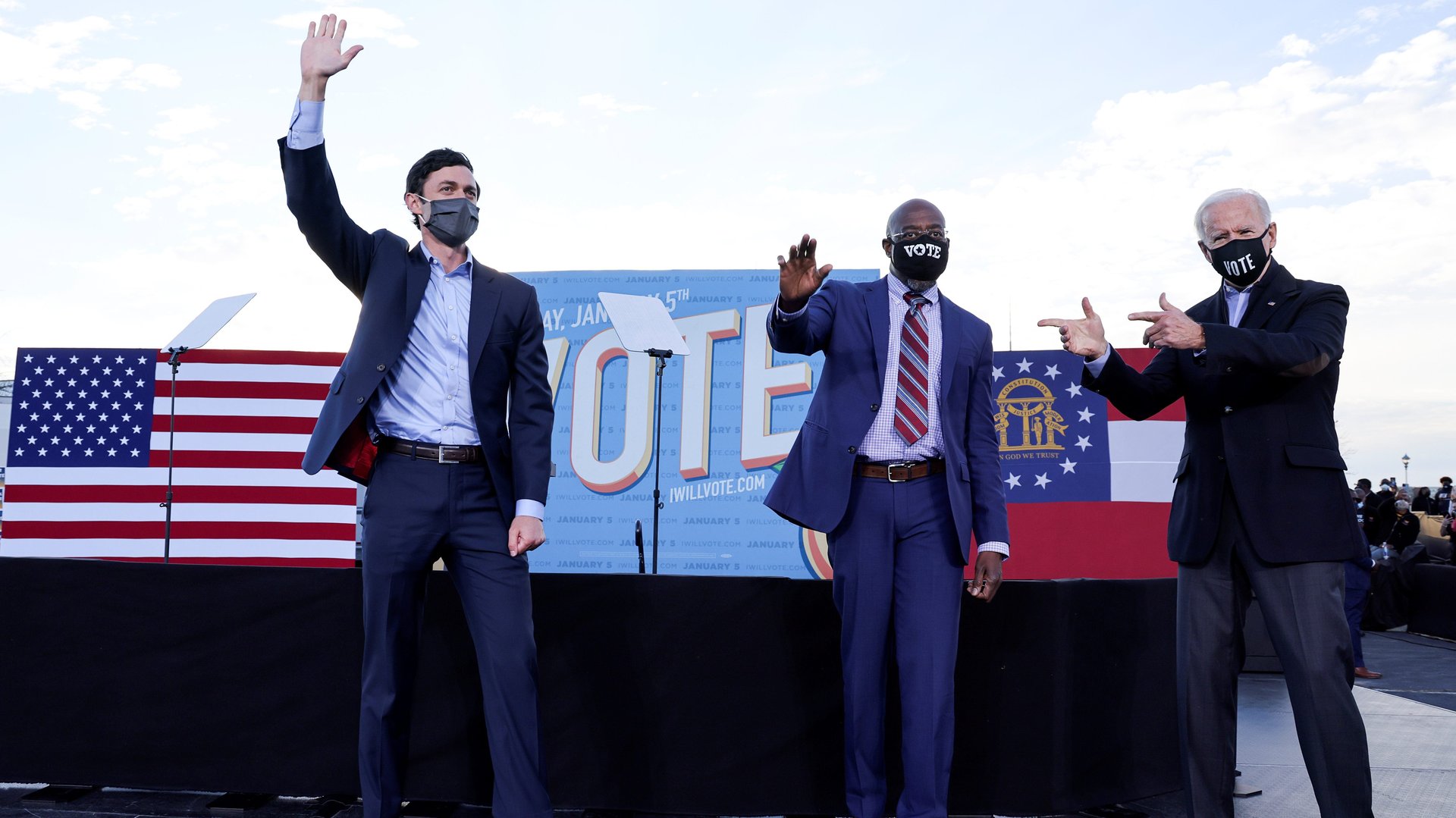

Georgia voters have struck fear in the hearts of Big Tech companies

As the dust settled on Georgia’s Jan. 5 Senate runoff races, and it became clear that Democrats would soon control the White House and both chambers of Congress, alarm bells began going off for tech watchers.

As the dust settled on Georgia’s Jan. 5 Senate runoff races, and it became clear that Democrats would soon control the White House and both chambers of Congress, alarm bells began going off for tech watchers.

“To be blunt, it’s a clear negative for Big Tech,” wrote Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives in a research note sent at 4am on Jan. 6, shortly after news outlets started calling the first race. In recent years, tech giants like Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google have been bracing for more regulation of their growing power, and Ives saw stormy seas ahead: “[W]ith a Senate now likely controlled by Democrats we would expect much more scrutiny and sharper teeth around FAANG names with potential (although still a low risk) legislative changes to current anti-trust laws now on the table.”

His reasoning is simple: While both US political parties take great joy in bashing tech companies, Democrats in the US House of Representatives issued a report on Oct. 6 laying out a clear legislative agenda for reining in Big Tech’s monopoly power. That included the prospect of banning dominant firms from buying up rivals and competing with vendors on marketplaces they control. Conservative judges and legal scholars, meanwhile, have spent the past four decades reworking US antitrust policy to make it much more difficult for prosecutors to win an antitrust case.

In last year’s divided Congress, the House report firmly staked out the Democratic party’s position on antitrust—but has gathered dust ever since. With one party in power, it’s significantly more likely that Congress can overcome its paralysis and get to the business of legislating. Stacy Mitchell, co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, which urges legislators to curb corporate power, argues this is the moment for lawmakers to pass sweeping monopoly reform laws in line with the House Democrats’ recommendations.

“What you don’t want is the Dodd-Frank of antitrust,” Mitchell said. She argued that the bank reform bill, passed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, was too toothless to actually change how banks operate and too confusing for the average person to understand. “That pathway would be terrible. ‘Oh, we fixed antitrust because we altered a little bit on the margins what the burden of proof is in certain merger cases.’ No no no, we have to go right at the problem.”

It’s unclear whether Democrats will be able to pass ambitious legislation with their thin majorities—they currently lead by 11 seats in the House and just one (vice president Kamala Harris’s tie-breaking vote) in the Senate. But at the very least, they will move quickly to fill an expected vacancy on the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the agency tasked with enforcing US antitrust laws. Political observers feared that, under a divided government, the Senate would never approve a nominee, leaving the agency deadlocked with two Democrat appointees and two Republican appointees.

“That would mean the FTC, at a very critical moment for addressing monopoly power, would be hamstrung to do anything,” said Mitchell. “Now that concern has been eliminated.”

Former FTC chair William Kovacic said staffing up the agency fast is critical as it prepares to wage a protracted legal battle with Facebook and scrutinize other well-heeled tech giants. “It’s extremely helpful to have your senior leadership in place in February or March instead of June, July, or August,” he said.

Kovacic added that a united government would also make it easier to pass laws directing more funding to the cash-strapped FTC. He also suggested that Democrats might take a page out of the Republican playbook and begin appointing liberal judges to federal courts who could gradually alter the American legal landscape and make it easier to argue antitrust suits.

Wall Street initially reacted to these newfound risks by tanking the tech-focused Nasdaq Composite. The index fell about 1% when markets opened on Jan. 6. But it quickly recovered, and overcame another stumble later in the afternoon when Trump supporters stormed the US Capitol.

“Right now, tech is the golden child and it can do no wrong,” said Ives, the market analyst. Bursting with confidence, bulls charged in to buy the dip the moment they saw tech stocks go down. “With a Biden presidency and a blue Senate, it’s viewed as a significant ratcheting down of China tensions, and that ultimately is a bigger risk to tech stocks than antitrust.”

It’s also possible that investors were simply relieved to finally know what they’ll face in the coming congressional term. “I don’t know the future, but to me, the ‘uncertainty’ of the election is arguably a bigger overhang than the actual outcome,” Tom Lee, head of research at Fundstrat Global Advisors, wrote in a note to clients.

If infighting among Democratic lawmakers keeps them from passing large-scale monopoly legislation over the objections of Republicans, bullish investors will be proven right. But the Big Tech firms that have fueled most of the stock market’s ebullient growth have a lot more to worry about now than they did before the Georgia voters spoke.