The British monarchy’s latest “treaty” asks CEOs to recognize the rights of nature

Prince Charles, heir apparent to the British crown, has asked the world’s CEOs to guarantee the rights of nature in capitalism.

Prince Charles, heir apparent to the British crown, has asked the world’s CEOs to guarantee the rights of nature in capitalism.

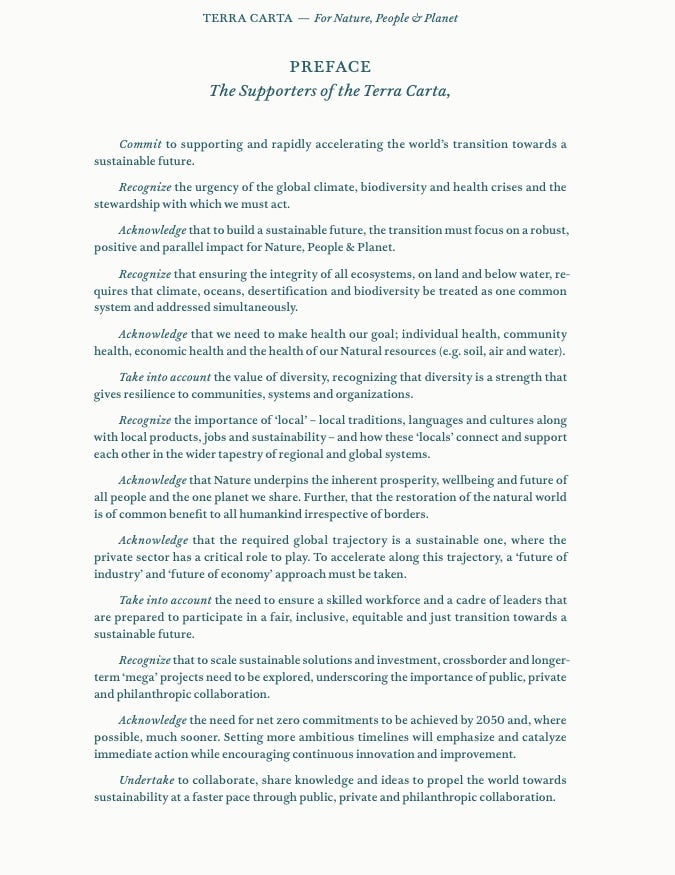

His 17-page Terra Carta, meaning Earth Charter in Latin, is a “recovery plan for Nature, People & Planet.” Released on Jan. 11, the document (designed by Sir Jony Ive, the designer behind Apple’s aesthetic) asserts that the “fundamental rights and values of nature” must be placed at the core of the global economy.

The charter aims to raise and invest $10 billion dollars (£7.3 billion) in this effort over the next decade. The voluntary framework commits companies and investors to ensuring their businesses are aligned with preserving the world’s biodiversity (protecting 50% of the biosphere by mid-century) and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 as part of the development of a more equitable, prosperous society.

History rhymes

If implemented as Prince Charles envisions, the Terra Carta would be as revolutionary a document as the one on which it is modeled: the Magna Carta.

That revolutionary British text, handwritten by feudal lords on sheepskin in 1215, was a treaty signed between British nobles and their king. Its principles, revised and enumerated over the years, have become the foundation for Western legal systems, enshrining the principle that sovereigns are subject to the rule of law and all citizens have the right to due process—an underpinning of British common law, as well as the US Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

The Terra Carta, of course, has no hope of ever reaching such legal status in the UK, or any country. Despite being written as a formal treaty, replete with a preface and articles, it creates no legal obligation for anyone, especially its intended subjects in the private sector. Companies that sign up can comply (or not) as they wish. So far, the Bank of America, AstraZeneca, HSBC, Heathrow Airport, and BP are supporting it.

At first glance, it makes the Terra Carta look like little more than the plea of a British royal family member to the new power brokers of modern times, multi-national corporations. “I can only encourage, in particular, those in industry and finance to provide practical leadership to this common project,” Charles entreated at a summit promoting the initiative, “as only they are able to mobilize the innovation, scale, and resources that are required to transform our global economy.”

Yet the Terra Carta may prove to be more powerful than it appears, says Bryce Rudyk, director of the climate program at New York University’s school of law. “The [Terra Carta’s intent] is something we’ve been trying to do internationally for a long time,” says Rudyk. “Most of climate change is caused by the private sector. Of course, all our international treaties are directed at states. This is directed at actors that can most solve this problem.”

The power of the Terra Carta, if it materializes, will be a framework that holds companies accountable for voluntary commitments. Companies that sign the charter, either to burnish their reputations or forestall more onerous domestic regulation, will be “reported on and updated annually,” according to the Terra Carta’s statement of intent (pdf).

This disclosure, argues Rudyk, has proven to be the key element of international agreements’ success. “One of the ways, honestly, we get states to comply with their international obligations is that we shame them.”

The power of international treaties is not rooted in coercion, according to researchers studying international diplomacy. A 1998 book called “The New Sovereignty,” written by two former US government officials and legal scholars, examined why countries complied with international regulatory agreements. The authors found enforcement was rare, costly, and burdensome. Most countries actually wished to meet their treaty obligations (outliers such as North Korea notwithstanding), and their failure to do so often stemmed from a lack of capacity rather than a deliberate attempt to evade responsibilities. Buttressing parties’ ability to deliver on their promises, and publicly reporting on their progress, helped secure international compliance.

This, in fact, is the model for the landmark Paris agreement on climate change. Emission reductions are not binding, ostensibly the point of the accord. Countries volunteer to submit national emission targets every five years with an expectation that they reflect the “highest possible ambition.” The only binding provisions are procedural: Countries must regularly report on their progress toward submitted emissions targets.

But that was enough to get the ball rolling. More than 60 countries have committed to eliminating net emissions by mid-century. The world’s biggest climate polluter, China, says its emissions will peak in 2030, earlier than promised, and then fall to net-zero by 2060. While not a panacea, countries are escalating their commitments faster than expected.

“In some sense, that’s what the Terra Carta is about,” says Rudyk. “Reporting on [commitments] and using that to push people into compliance.”

The Paris Agreement, despite wielding no power over companies, has sent a clear market signal—net zero emissions by mid-century—prompting the world’s largest companies and investors to adopt ambitious, voluntary climate action. Groups such as Climate Action 100+ (an investor coalition) and Science Based Targets have enrolled thousands of firms in emissions and reporting requirements aligned with Paris targets.

While that suggests the Terra Carta is more than an empty exercise, it’s also evidence it won’t be enough to finish the job. “Progress [on emission cuts] has been made on almost every front,” said the non-profit World Resources Institute, “but it has not been anywhere near fast enough.” Even if countries achieve their current emission commitments under the Paris agreement, the United Nations says, the world is on course to warm by at least 3° Celsius this century—well beyond the 1.5°C aspiration stated in the treaty.

When painful cuts need to be made, a document of principles alone is unlikely to close the deal. History has lessons here too. The Magna Carta, at its inception, was an unlikely guarantor of freedom. Few at the time gave it much credence. A weak monarch, King John, granted novel rights to his subjects by stamping a wax seal on a piece of parchment, and then promptly asked the Pope to nullify the contract (which he obligingly did). For centuries is was honored mainly in the breach. But after centuries of pitched legal (and sometimes actual) battles, those rights and freedoms were enshrined in the legal institutions of western society. And that battle continues today.

If anything does come of the Terra Carta, it’s will no doubt endure a similar evolution, as one pitched skirmish among many to ingrain its revolutionary principles into the workings of the global economy.

That evolution needs to be rapid to be effective, though. It took more than 700 years for the full expression of the Magna Carta’s principles to be realized: In 1928, Britain granted all its adult citizens equal rights to vote, securing its place as a full democracy. The climate can’t wait as long. With only 30 years left to eliminate the global economy’s emissions, states the Terra Carta, “time is fast running out.”