What happens if Joe Biden dies in office?

As of noon today, Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr is the 46th president of the United States of America.

As of noon today, Joseph Robinette Biden, Jr is the 46th president of the United States of America.

He is the oldest president to serve the country. At 78, he is older even than the older president to leave office, Ronald Reagan, who was still 77 (for a few days) at the end of his second term. That is almost two years older than the current life expectancy for a US-born male, which is 76.3 years (the lowest of all wealthy countries) and 14 years older than the male life expectancy of an American man born in 1942.

It’s happened before

A seamless transition of power in case of unexpected events is a hallmark of a functioning democracy. Biden is healthy and vaccinated but given his age, it’s responsible to ask what happens if he gets ill while in office or, worse, dies. After all, that has happened to a remarkable 17% of US presidents—eight out of 46.

In 1841, William Henry Harrison (president number nine) died of typhoid or pneumonia at 68.

In 1850, Zachary Taylor (president 12), died at 66, possibly of cholera, potentially caused by eating too much dry fruit at a celebration.

In 1865, Abraham Lincoln (president 16), then 56, was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a confederacy supporter.

James Garfield (president 20) was also assassinated, in 1881 at the age of 48, by Charles Guiteau, a lawyer who believed he deserved a reward for helping the president’s election.

William McKinley (president 25) died at 58 in 1901, also assassinated, by anarchist Leon Czolgosz.

Warren Harding (president 29) died at 57 in 1923 of a heart attack and was not, as it was rumored at the time, poisoned by his wife Florence, to whom he was unfaithful.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (number 32) died in 1945 at the age of 63, after years of poor health.

In 1963, John F. Kennedy, America’s 35th president, was fatally shot in Dallas, Texas. At 46, he was the youngest president at the end of his office.

Who’s next

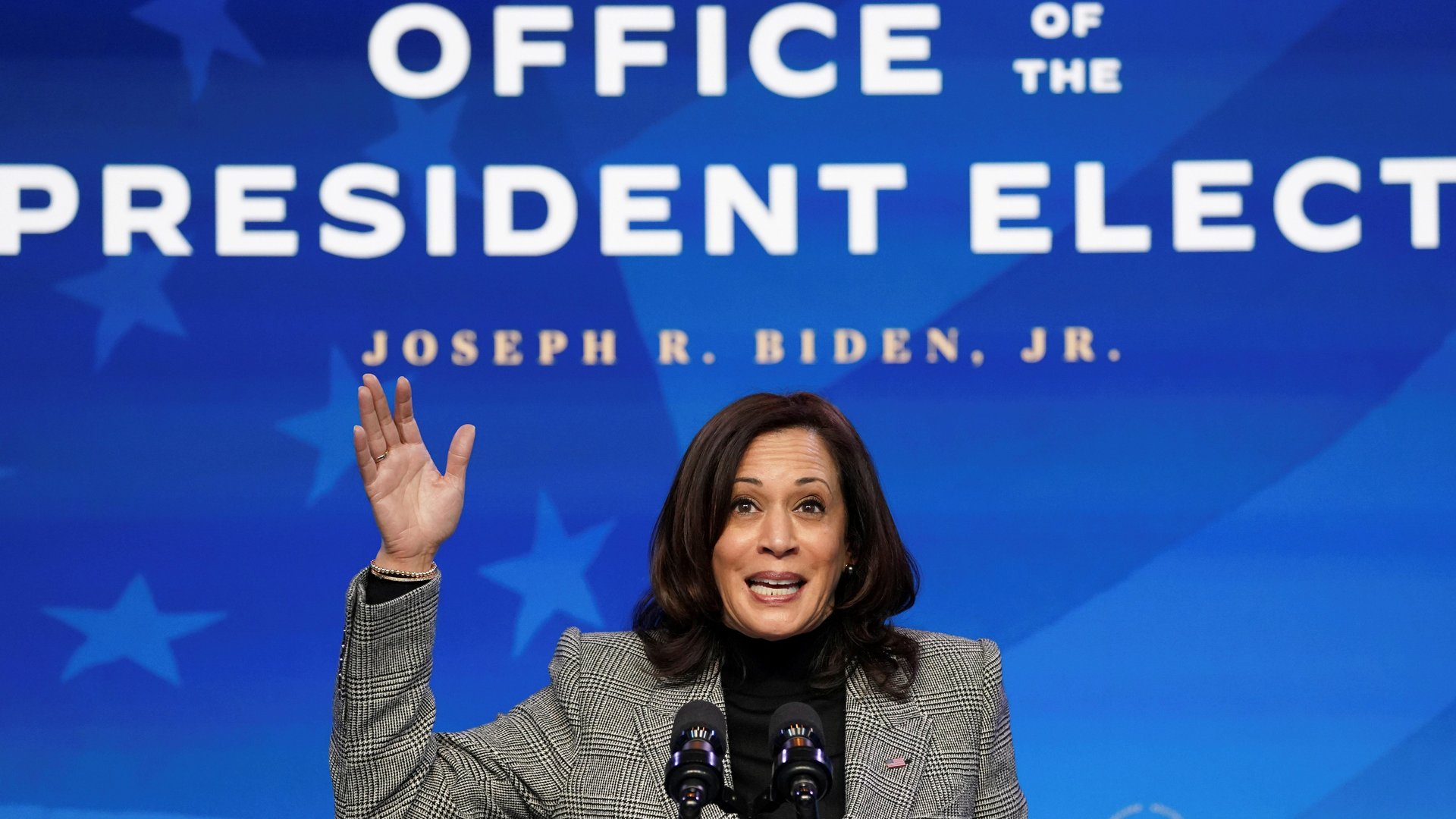

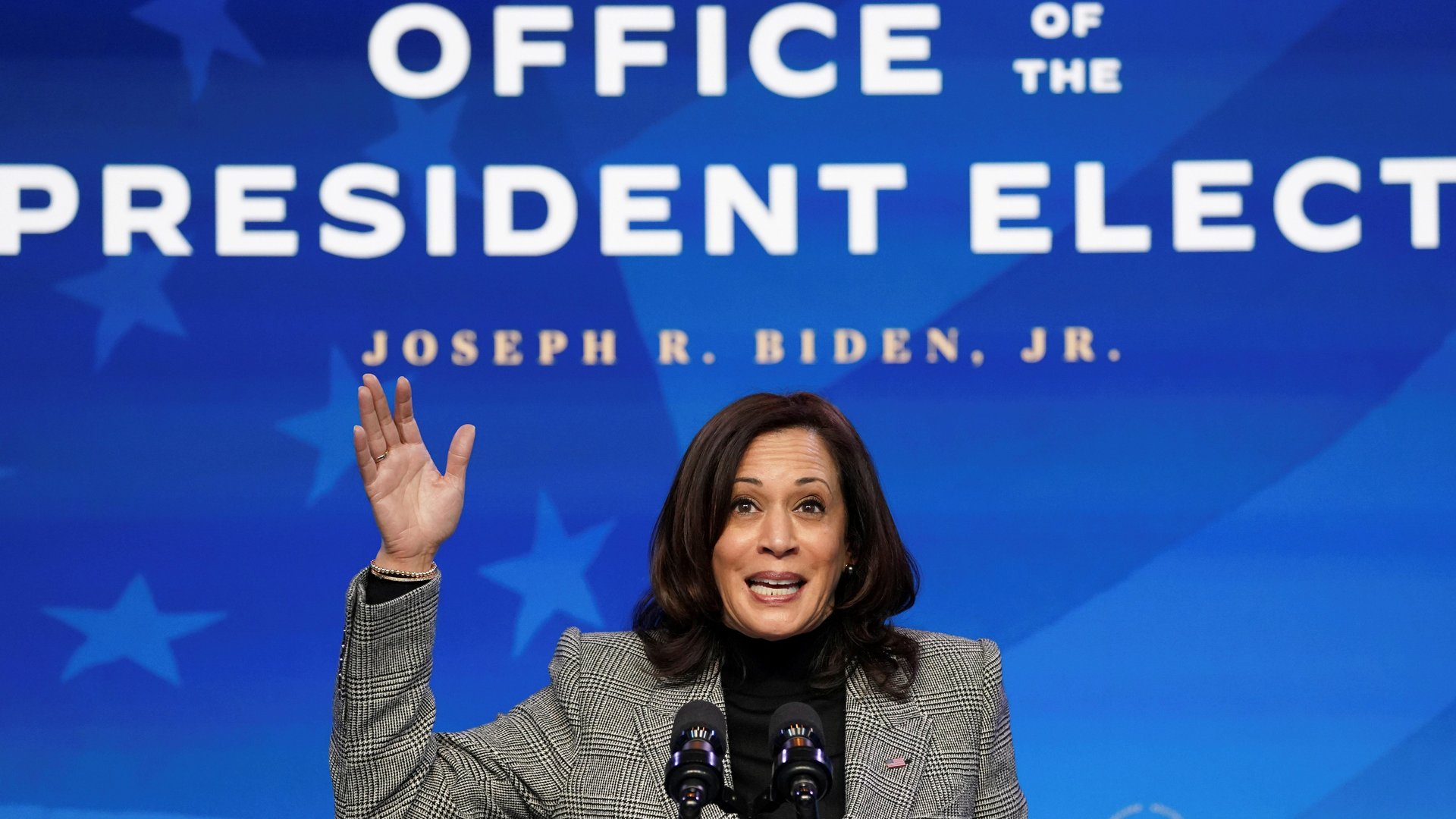

The 25th amendment of the US constitution, which deals with “presidential vacancy, disability, or inability,” is clear on what happens if the president dies, resigns, or is removed from office. The vice-president (in this case, Kamala Harris) is sworn in to take over the presidential responsibilities until the end of the mandate.

Similarly, if the president is temporarily unable to serve, they have to communicate it in writing to the president pro tempore of the Senate (who presides over the Senate in lieu of the vice-president) and the Speaker of the House. The vice-president then takes on presidential responsibility until the president lets the Senate and House know they can resume their duties. This has happened three times in US history: For about eight hours in 1985, then vice-president George H W Bush acted as president while Ronald Reagan underwent colon cancer surgery. In 2002 and 2007, for two hours each time, vice-president Dick Cheney acted as president while George W Bush underwent two colonoscopies under anesthesia.

If the vice-presidential seat is vacated, the president can nominate a successor, who then has to be confirmed by a simple majority vote in both houses of Congress.

The full extent of this provision was tested during the Richard Nixon presidency. First, his vice-president, Spiro Agnew, resigned in October 1973. Gerald Ford, then the minority leader, was named Agnew’s replacement by the president and voted upon by Congress. Less than a year later, in August 1974, Nixon resigned, and Ford was sworn in as his successor, leaving the vice-presidential office once again vacant. Ford appointed former New York governor Nelson Rockefeller as his vice-president, and he was approved by Congress. All positions were then held until the end of Nixon’s second term in 1977.

But what happens if both the president and the vice-president are unable to serve?

The line of succession, as established by the 1947 presidential succession act, starts with the Speaker of the House (currently, Nancy Pelosi) after the vice-president, then the president pro-tempore of the Senate (currently, Republican senator Charles Grassley of Iowa, but will be Democratic senator Pat Leahy of Vermont after today), and then cabinet members, starting with the secretary of state.

However, the presidential succession act says officials beyond the vice-president in line of succession would only be acting as president, not become president, after resigning from their office. They will only hold the office until a new president can be chosen. This might happen, for instance, if the vice-president was only temporarily incapacitated and, once able to resume the role, could be sworn-in as president. Otherwise, the acting president holds the job—and is paid for it as much as an actual president—until the next presidential election and inauguration. However, because this unlikely chain of events has never occurred, it is not clear what would be the limitations of the acting president’s power as compared to the actual president.

Correction: When he became vice-president, Gerald Ford was minority leader, not speaker of the House.