Mega-mergers are back, even though the evidence says they rarely succeed

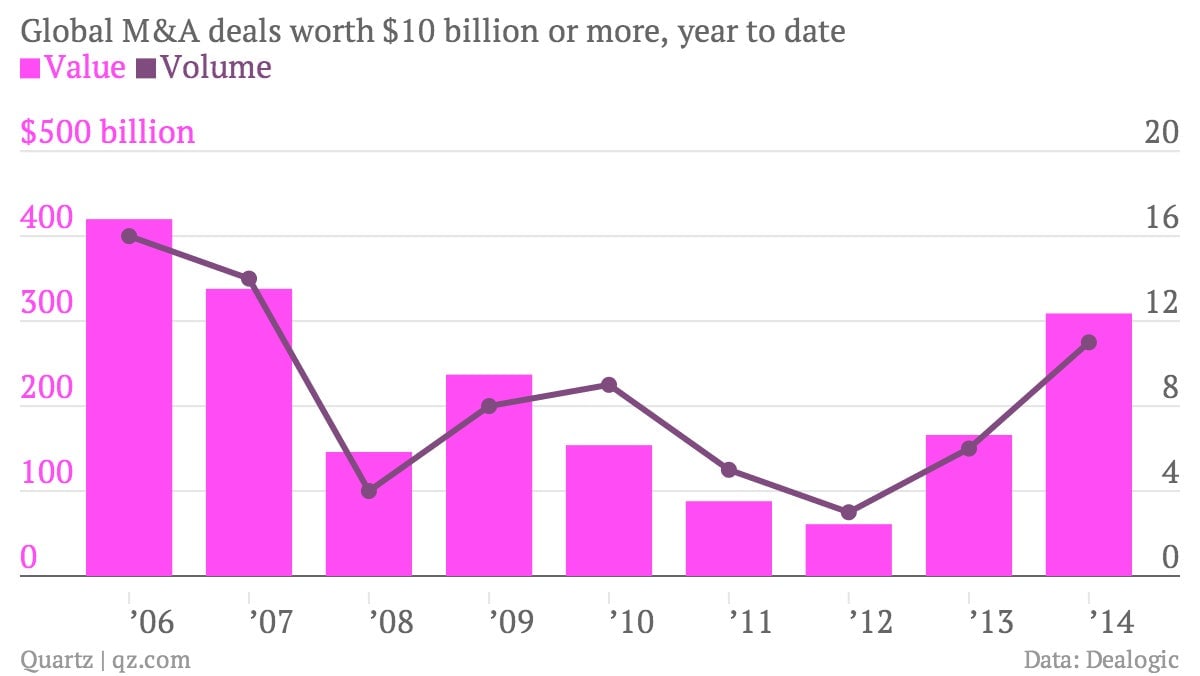

News from the cement industry rarely quickens the pulse. But when Holcim and Lafarge revealed the details of their proposed merger (pdf) this week, the numbers were gaudy enough to attract attention. The $43 billion cement merger is the second-largest deal announced this year, after Comcast’s $45 billion Time Warner bid. It is also the latest in a series of $10 billion-plus mega-deals, which are making a comeback in 2014 after several quiet years:

News from the cement industry rarely quickens the pulse. But when Holcim and Lafarge revealed the details of their proposed merger (pdf) this week, the numbers were gaudy enough to attract attention. The $43 billion cement merger is the second-largest deal announced this year, after Comcast’s $45 billion Time Warner bid. It is also the latest in a series of $10 billion-plus mega-deals, which are making a comeback in 2014 after several quiet years:

The combination of Switzerland’s Holcim and France’s Lafarge would create a $43 billion giant more than twice as large as its closest competitor. The group says it will shed assets worth more than $6 billion in sales to win antitrust approval, after which the slimmed-down operation will generate some $2 billion in cost savings.

Chronic overcapacity in the global cement industry means that the companies were already trying to cut costs and pay down debt. The tie-up—a one-for-one share swap billed as a “merger of equals”—has more to do with two overindebted players fighting broader industry trends than one firm taking advantage of a rival. Perhaps that’s why shares in both companies jumped on the announcement, whereas in most deals the market reaction reveals a clear winner and loser.

The bigger they are, the harder they fall

The investor reaction is also somewhat curious because mega-deals tend to flop. A study by Accenture found that the biggest deals fared much worse than smaller transactions in terms of market returns. Academics have also observed that buyers tend to pay smaller premiums in the biggest deals, which nevertheless end up destroying more value than the others. The complexity of integrating two large groups together is usually cited as a key factor in mega-deals failing to deliver on their promises.

The Holcim-Lafarge fusion adds extra complexity, given that it is a true merger of equals. With two parties on equal footing, making decisions on the course of the combined group can be slow and politically charged. For this reason, the research isn’t very kind to the performance of these types of deals.

The purportedly friendly merger of Duke and Progress Energy quickly descended into acrimony, while what started as a merger between miners Glencore and Xstrata proved so much of hassle that in the end the former simply took over the latter. Telecoms equipment makers Alcatel and Lucent thought they could better withstand the disruption in their industry together than alone, but things haven’t gone so well of late.

However deals are structured, they are bound to get bigger, according to a new survey of executives by EY. Twice as many managers as last year said they were on the prowl for billion-dollar deals. Shareholders will just have to hope that these companies have done their homework before pulling the trigger on mega-deals, since all available evidence suggests that the odds are stacked against them.