When to sell? The game theory of GameStop

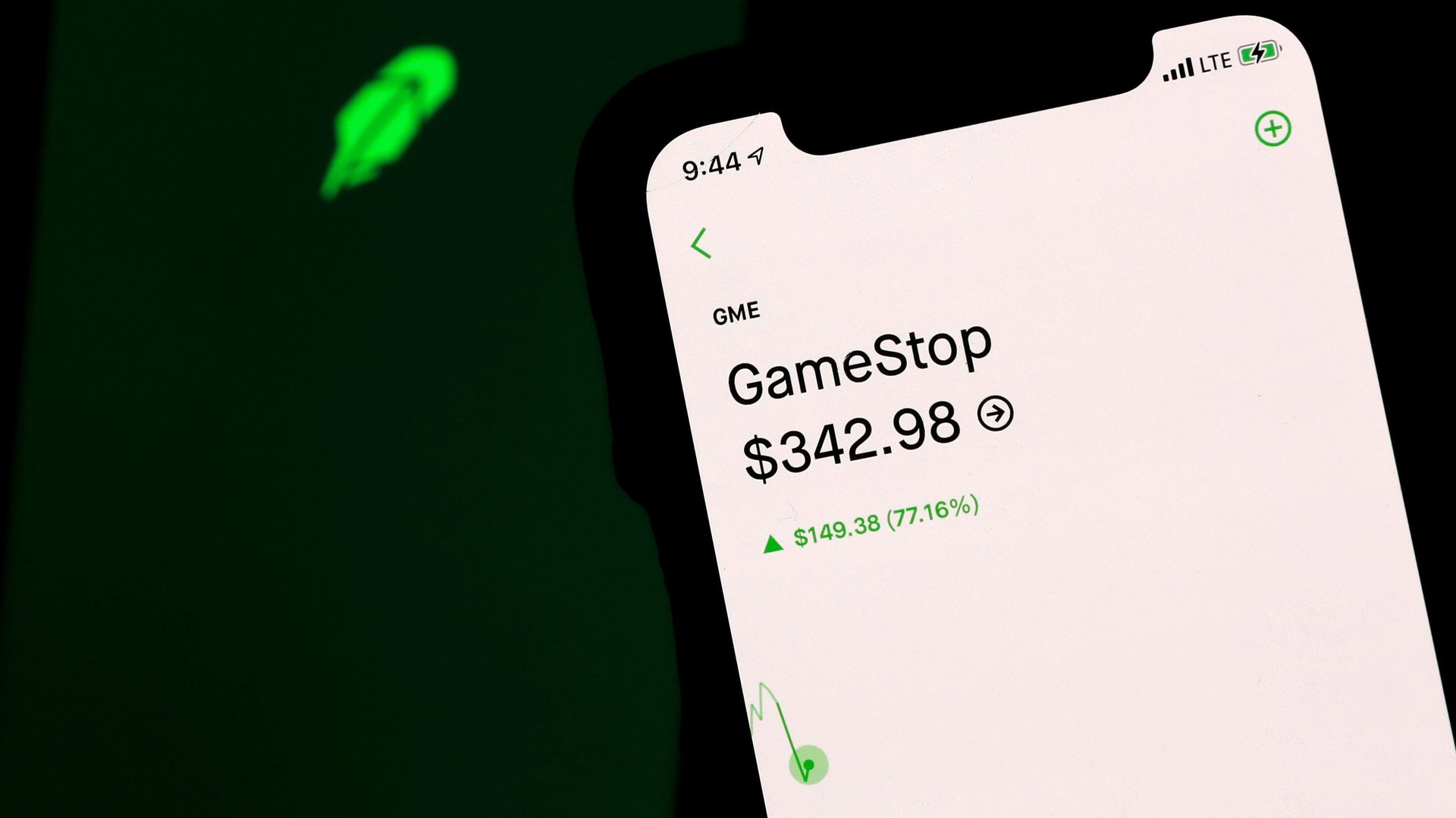

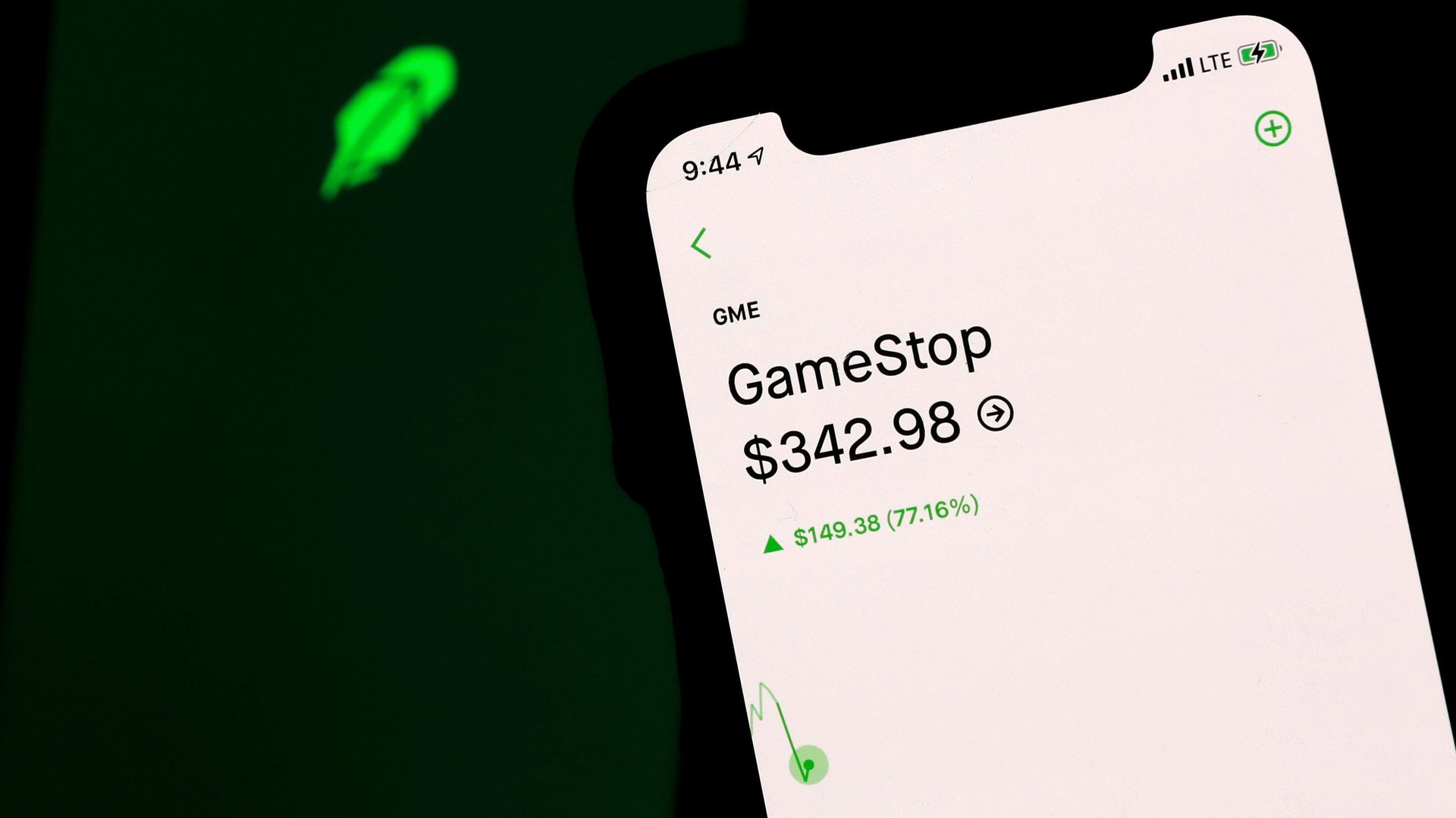

Eventually, the party will end. Even enthusiastic members of the Reddit forum WallStreetBets, who have been boosting the stock price of GameStop over the last two weeks, agree that the company isn’t worth its current valuation. Which means the price is likely to drop back down—and drop back rapidly at that.

Eventually, the party will end. Even enthusiastic members of the Reddit forum WallStreetBets, who have been boosting the stock price of GameStop over the last two weeks, agree that the company isn’t worth its current valuation. Which means the price is likely to drop back down—and drop back rapidly at that.

So if you’re a retail investor who has bought GameStop shares, how can you make as much money out of it as possible, before the great offload of stock begins?

The question of when to sell is at the core of any bull run or bubble, and calling the peak of any speculative run is seen to be impossible. In principle, this is the case with GameStop too, but with a twist. Abstractly, WallStreetBets’ members have been calling to push the price “to the moon,” but they’ve also emphasized a number: $1,000 a share. Markets don’t ordinarily supply that kind of information in advance. So of the many possible scenarios of the end of this GameStop saga, the $1,000 ceiling gives rise to one in particular.

If GameStop’s price continues upwards, the trick will be to sell the stock as close to $1,000 as possible, but before many other people start selling as well. This involves game theory considerations: trying to out-strategize your competitors to optimize your own profits. Hypothetically, you might sell at $900, but thousands of others may have the appetite to wait until $1,000, so you wouldn’t have made as much money as them. Or you might suspect that others will wait until $1,000 and hold your stock, only to find people exiting at $950 and the value of your stock dropping in this mass sell-off.

The problem is: As the price approaches $1,000, finding buyers for GameStop stock becomes harder and harder. In regular situations, people buy a high-priced stock thinking that the future will be even brighter, or at least that the price won’t plummet. Here, because WallStreetBets has bandied about the $1,000 number, no buyer will bite at that price. Or even at a lower price: Why purchase a volatile stock for $975 if it promises, at most, a further $25 rise in value?

Holders of GameStop stock will thus have to practice a version of the thinking laid out in a Keynesian Beauty Contest, a hypothetical model that Keynes proposed in 1936. If a newspaper runs photographs of a hundred faces and invites readers to vote for the six prettiest, promising a prize to anyone whose picks tally with the six who received the most votes, a reader has to think not of her own tastes but of the crowd’s. She has to guess at which faces others might find pretty, or better yet, which faces others think still others might find pretty. This doubled and redoubled guessing at sentiment is often part of stock market plays; a good time to sell is when you think others think a stock is overvalued. With GameStop, the thought process is slightly altered. At what price before $1,000 will others think there will be no more buyers to be found?

In this scenario, it isn’t unreasonable to think that the stock will never reach $1,000. As the ceiling approaches, people will worry about buyers drying up, so they’ll start to sell. That will force the price down, which will prompt more people to sell, and so on. The price can only ever be asymptotic to $1,000—like a curve on a graph, drawing closer and closer to an axis but never quite touching it.

This is all assuming, of course, that Redditors behave as what economists like to call “rational actors”—people who look out for their own gain. The Redditors don’t see themselves in that vein; they believe they’re irrationally united to continue their short squeeze. “Those hedge fund managers probably all studied game theory at Yale and are going through their entire playbook of what to do against rational actors,” one WallStreetBets member wrote last week. “Too bad their ivy league degrees didn’t teach them what to do when coming up against millions of retards and autists.” But the choreography of this short squeeze will be threatened if members suddenly turn “rational,” breaking off to cash out. That is why they keep calling for each other to be “strong,” to “hold the line.” If a few cards slip, the entire castle will start to tumble.