One solution to pandemic unemployment? Working less

Around 90 years ago, president Franklin D. Roosevelt found the US in a similar state to most pandemic-hit economies today: beset by a severe economic shock and rising unemployment. One of his solutions was a radical one: to ask people to work less, so that more people could work.

Around 90 years ago, president Franklin D. Roosevelt found the US in a similar state to most pandemic-hit economies today: beset by a severe economic shock and rising unemployment. One of his solutions was a radical one: to ask people to work less, so that more people could work.

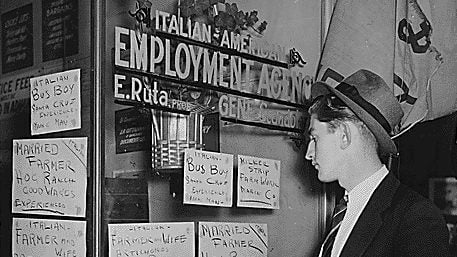

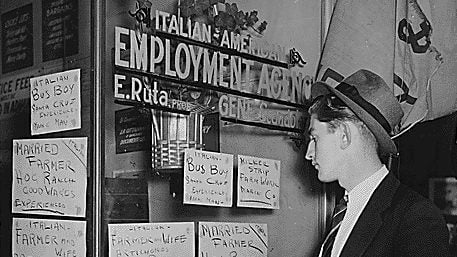

When companies signed the Presidency Reemployment Agreement in 1933, they agreed to wage brackets and price caps. But they also agreed to shrink the working week of their employees.

Artisans, factory workers, and mechanical workers, for instance, would work a maximum of 35 hours a week through the year, their employers promised, down from the usual 45-50; clerks, accountants and sales staff would work no more than 40. Businesses that signed up would be able to advertise their involvement in the national recovery with a poster featuring a blue eagle and the words “We Do Our Part.” (“Those who cooperate in this program must know each other at a glance,” Roosevelt said in a radio address, urging consumers to seek out businesses bearing the eagle.) The government followed up by checking that firms were sticking to their promises. One study, from 2011, found that 1.34 million people found work through the agreement in just over four months.

In Europe, as in Asia and the US, the pandemic has sparked a new gravitation towards the shorter working week. Last year, IG Metall, Germany’s largest trade union, began bargaining for a four-day week, because the auto industry was facing the loss of at least 300,000 jobs. On Thursday (Jan. 28), Spain set aside €50 million in incentive funding to companies willing to try a four-day week. And earlier this week, a British trade union, Unite, voted for a shorter working week at the Airbus factory in Broughton, Wales.

Unite had begun exploring the option last July, said Daz Reynolds, the union’s convenor at Airbus. “We needed to have an alternative to furlough,” Reynolds said, referring to the scheme by which businesses sent some of their employees on what amounted to paid leave, with the government paying 80% of their wages. Roughly 400 jobs were in danger of being made redundant; in total, 6,000 people work at Airbus Broughton, more than the population of the eponymous town. Under the negotiated agreement, which runs for 18 months beginning May 2021, all employees will work either 5% or 10% fewer hours—time knocked off the present 35-hour work week that Airbus follows in Broughton. They’ll get paid 5% or 10% less as well, although Airbus has promised to pay a third of any lost wages back to the employees.

Economists and activists had already been pushing for a shorter work week in Europe even before the coronavirus hit, but the pandemic’s effects make the idea even more worthwhile, said Aidan Harper, a member of the 4 Day Week Campaign in the UK. “The idea is that you reduce the working week to distribute work more fairly across the economy, and so reduce unemployment,” he says. “People staying in work and having money in their pockets—that’s essential for an economic recovery. They spend locally, they employ more people, the money circulates. It’s essential that people spend during a downturn.”

Last August, the think tank Autonomy published research showing that, if the public sector switched to a 32-hour week, it would create between 300,000 and 500,000 new full-time jobs, at a maximum cost of £9 billion—6% of the current spend on public sector wages.

For a brief period, it looked as if the UK might move in the opposite direction. In mid-January, the government prepared to review its adherence to the European Union’s Working Time Directive—which the UK is no longer compelled to follow, post-Brexit. The directive gives people the right to work no more than 48 hours a week, although people who have second jobs or take on unpaid work frequently overshoot that limit. After opposition from the leftwing Labour Party and unions, Kwasi Kwarteng, the business secretary, said last week that the review wouldn’t take place: “We will not row back on the 48-hour weekly working limit.”

Activists like Harper offer plenty of proof that people are as productive—if not more—in shorter working weeks as in full-length ones. But as the economy goes on to recover, and as companies try to make up for a year of struggle, selling them on the idea that they should permanently want less of their employees’ time won’t be easy. And it won’t necessarily be easy to convince workers either.

In the decades after the Presidency Reemployment Agreement lapsed, workers in the US frequently indicated they preferred a longer work week. The worry that less working time means smaller pay checks is deeply ingrained. “We will always look to improve our members’ terms and conditions,” Reynolds said, when asked if Unite would support shorter work weeks across the economy. “But we need to maintain salaries also.”