For some voters in Mumbai, this election’s all about toilets

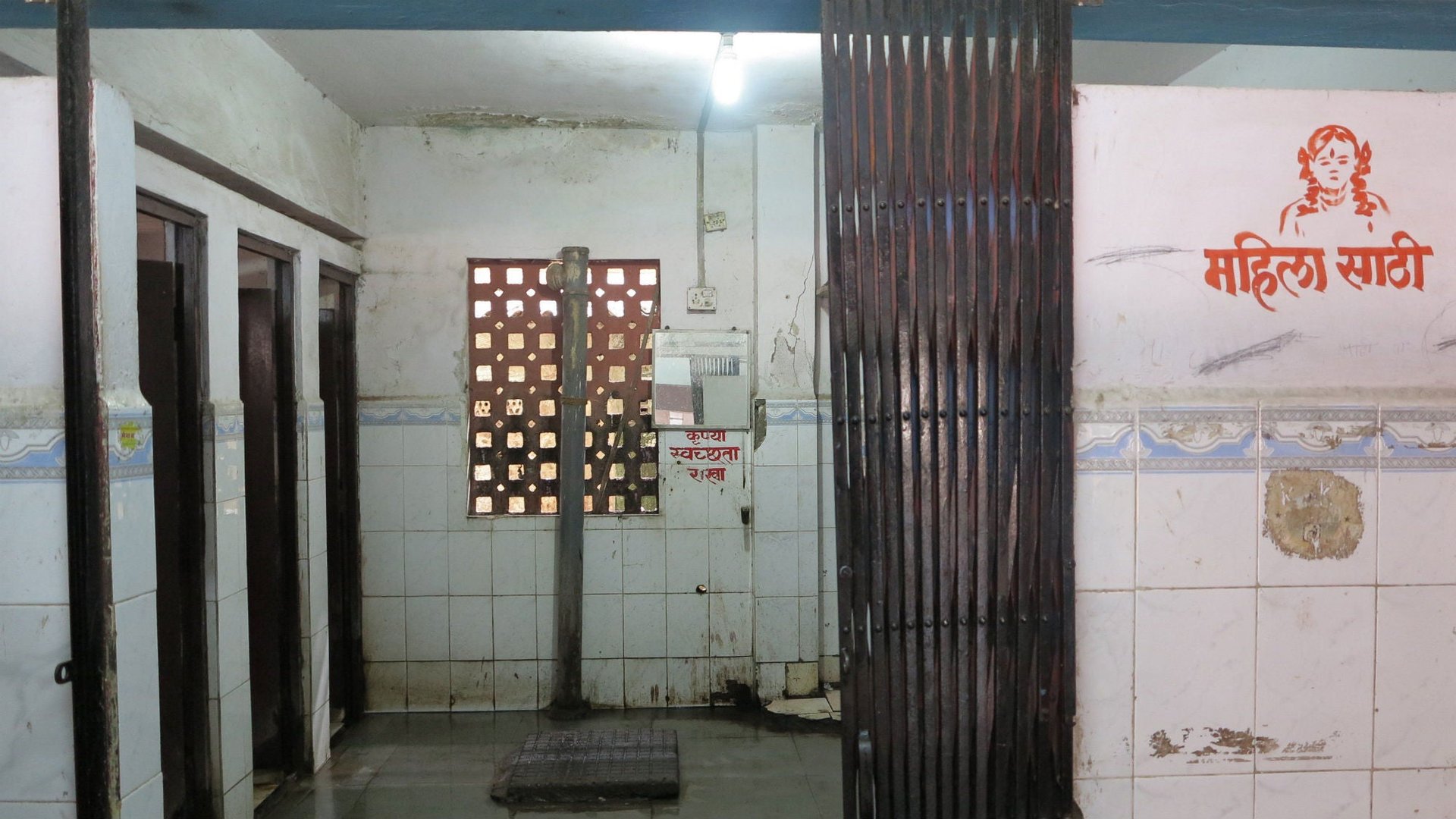

It’s the sort of bathroom you smell before you see. The floor is a skating rink of mud. You need a torch to watch your step.

It’s the sort of bathroom you smell before you see. The floor is a skating rink of mud. You need a torch to watch your step.

And yet Usha Kale strolls in without hesitation.

“What choice do I have?” she asks.

It’s a question she hopes will be answered when Mumbai goes to the polls this month.

Kale heads one of the 53% of urban Indian households that, according to the 2011 census, do not have toilets, so she relies on a public toilet block in Govandi, the Mumbai suburb where she lives and works. In addition to the degrading conditions—many of these facilities have no lights, soap, or trash bins, not to mention water—women like Kale must pay every time they use the toilet.

Public toilets in Mumbai cost 2 rupees (under 4 cents) per use, but by law, men and women are supposed to have free access to urinals (the idea being that toilets require running water, which costs money, and urinals do not). But there’s a catch: the city has 2,466 urinals for men, but not a single working urinal for women, which looks like a squatting toilet with a channel so narrow only urine can pass through.

So women are forced to use a toilet when it’s a urinal they need, and to pay every time.

“[The attendant] goes rap rap rap on the table in front of him as soon as you walk in, demanding, ‘paise de,’” or hand over the money, Kale tells me. “And all you want to do is pee. But will the average Indian woman look a strange man in the face and talk of piss? And if she does, like I do, he’ll only reply insolently, ‘How do I know if you’re shitting in there or pissing? Pay me or scram.’”

Kale is one of the dozens of activists behind the Right to Pee Movement, a coalition of 36 non-profits arguing that Mumbai’s women should be able to pee for free, same as men.

Since 2011 the activists have been pressuring the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC)—the civic body that contracts private companies to build public toilet blocks, to add women’s urinals to existing blocks. The BMC’s initial response was indifferent. “They asked us to identify toilet blocks with space to add urinals,” says one of Kale’s fellow activists, Mumtaz Sheikh. “Did they ask us to show them where to lay down railway tracks? No. But when it comes to the aam admi (common people), and particularly women who happen to be poor, they won’t do any of the legwork.”

The activists quickly identified five toilet blocks that could be renovated. At the time, Subhash Darvi, an officer representing the BMC in the talks, told me that the corporation was “100% in favor of women’s urinals.” But then the BMC stalled, repeatedly pushing back scheduled meetings. The activists suspect that the BMC didn’t contractually obligate the companies to build women’s urinals. As a result, the companies would be within their right to refuse to do so.

The stalemate forced the activists to rethink their strategy. They decided to circumvent the BMC, and approach politicians in the state government instead. They also upped their demands, asking not just that existing toilet blocks be renovated, but also that new toilet blocks be built for and managed by women.

One of the high-powered politicians that the activists courted was Varsha Gaikwad, the state cabinet minister in-charge of women and child development.

Gaikwad was impressed by the public support the campaign had received—more than 50,000 handprinted signatures and reams of ink in the local and national newspapers, not to mention TV appearances. In 2013 she helped introduce a government policy that mandated the construction of a women’s toilet block every 20 kms (12.4 miles).

In many parts of the world this figure—a concession to land scarcity and limited resources—would have been met with howls of outrage. In Mumbai it was greeted with elation. The unprecedented acknowledgement of a woman’s right to a public toilet was seen as a victory not just for the fight for better sanitation, but for the women’s movement.

It was then, says Sheikh that the BMC returned her calls, even pledging 75 lakh rupees ($120,000) to a pilot project to build 11 toilet blocks for women.

Although the planning is still in the early stages, the elections have had a promising impact. In person and in campaign speeches several state-level politicians pledged around 2 lakh rupees ($3,000) each from their constituency development funds toward the pilot project. They also turned up the pressure on the BMC. “They are now less corrupt,” says Kale of the BMC officials. “It’s because they accepted bribes, in the first place, that they had to also accept when a contractor defied them.”

Eleven additional toilet blocks isn’t very much in a city of roughly 20 million people. But consider the challenges that the activists have already surmounted.

A cocktail of cultural squeamishness and class, caste and gender discrimination forces more than half of India’s population of 1.2 billion people to defecate outdoors. It is such a common sight even in modern cities that most streets are minefields to be maneuvered with eagle-eyed vigilance. Open defecation creates toxic bacteria in the air and pollutes water resources, spreading disease. While men and children relieve themselves freely, women wait until dark to crouch in alleyways or, if they live on the outskirts of the city, in the shadow of the tall stalks of the closest field. The long gaps make them vulnerable to gynecological, urinary, and kidney infections.

All the sneaking around isn’t just terrible for their health, it is also dangerous. Women in India are vulnerable to sexual assault even in crowded places in the daytime. At night their vulnerability is only amplified.

Poor sanitation also hurts the economy. Mumbai has the largest number of working women in the country. The majority works in the informal sector—as domestic labor and in sweatshops packed into slums. According to a 2011 World Bank report,“poor sanitation results in poor health, absence from work, and restricted mobility … (a) loss of social and economic opportunities, and incomes.”

The desperate need for toilets is now making an impact on political agendas. In 2012, when India’s rural development minister said that the country needed more “toilets than temples” he was met with outrage. But the manifestos of all the major political parties in this election mention toilets. The ruling Congress party even called access to a toilet a legal right.

India’s deep class stratification is one reason why this promise has been so long coming. When Kale stood on railways platforms soliciting signatures in support of Right to Pee, the middle-class women, she says, sailed past. Those who stopped only did so to underscore their privilege. “Who needs public toilets when you have toilets in malls?” they sneered.

Eleven toilet blocks will change the lives of thousands of Mumbai’s women. A toilet block every 20 kms will change the lives of hundreds of thousands of women. Neither goal will be accomplished easily. But the Right to Pee activists are in for the long haul. After the final vote is counted, after promises made under pressure are likely to be delayed or even broken, these women will still be on railway platforms and on public streets and outside politicians’ doors demanding to be heard and insisting on change. The answer “no,” they say, is not an option.

“Ours is a movement of sewage cleaners and sweepers, flower sellers and fishwives,” says Kale, with a confident smile. “Just the sort of women who are used to a fight.”