The rise of borderless dating

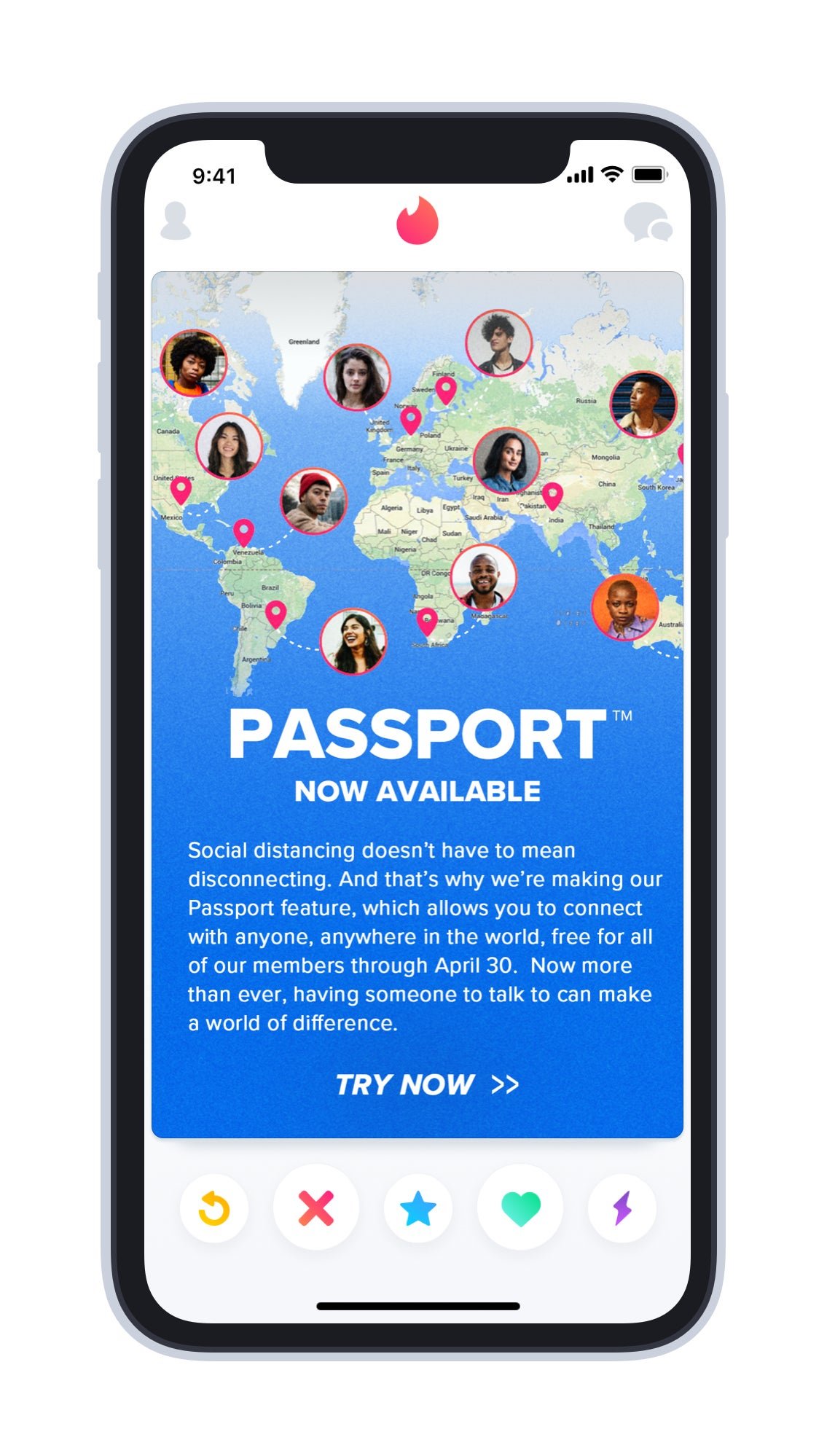

In the early days of the pandemic, Tinder users, stuck at home, started teleporting themselves en masse into other countries to check out the dating pools, and maybe engage in some cross-border flirtation. They weren’t physically there, of course, but the app’s “Passport” feature allowed them to change their location and indulge in the fantasy.

In the early days of the pandemic, Tinder users, stuck at home, started teleporting themselves en masse into other countries to check out the dating pools, and maybe engage in some cross-border flirtation. They weren’t physically there, of course, but the app’s “Passport” feature allowed them to change their location and indulge in the fantasy.

The feature, normally available with Tinder’s paid subscriptions, was so popular that the company made it free for everyone for a month. Tinder competitor Bumble followed suit, giving users the option to set their location filters “nationwide,” as opposed to the usual 100 miles.

What was a bit of escapism for bored and lonely users and a marketing boon for online dating companies speaks to a larger phenomenon. A seemingly growing number of people are inspired to date beyond their immediate physical community, even when travel is limited. For better or for worse, the “borderless” trend on online dating apps has been percolating for some time, with the pandemic giving it a boost. Will it continue when people can meet up in person again?

WFH, date wherever

Tinder has offered its “Passport” feature since 2015. Before the pandemic, daters used it to find matches in places they were traveling to.

Antonio, 34, is from Costa Rica and lives in Barcelona, Spain (Quartz has changed his name to protect his privacy since he’s from a small conservative country). He has used Tinder Passport several times before traveling to other European countries prior to the pandemic. Antonio is not looking for a long-distance relationship, he just wants to enjoy his time while abroad.

“You pre-swipe, say, a week before you fly, and then by the time you get there, you’ve been having conversations with people,” he said. “And then you say: ‘Okay. This girl, or this girl, I would like to meet them, I would like to go on a date.”’

Location has started mattering less for people’s lives in general. Remote work has allowed people to move around more freely, and changing location on an app lets users meet people before getting to their new WFH location. Long-distance relationships are easier to maintain thanks to technological developments like texting and video chatting.

Nicole Parlapiano, vice president of marketing for North America at Tinder, also says that Gen Z has a more relaxed, open approach to dating, partially just by virtue of being young. “This is such a hopeful and positive generation, that there’s always the possibility that they could travel somewhere.”

The progressive views of this generation and its openness to a diversity of experiences may also be a factor. American Gen Z-ers are “less likely than older generations to see the United States as superior to other nations,” according to research by the Pew Research Center, and hold nationalism and patriotism in lower regard than their elders, according to Morning Consult.

“I think the world’s getting smaller. What matters is good interaction, good conversation. And you can jump on a plane, you can get in a car,” said Geoff Cook, CEO of the Meet Group, which owns streaming app MeetMe.

Expanding horizons during lockdown

There’s a meme on TikTok that’s been popular during the pandemic: the user reports that while stuck at home, they changed their location setting on Tinder using its “Passport” feature to Sweden, or Brazil, or Spain, and posts a series of screenshots of their matches—a catalog of dazzlingly beautiful people they’d found while virtually traveling.

It’s hard to tell how many users were using such features just for fun or in search of TikTok clout, and how many were hoping to have some sort of meaningful connection. But it’s also clear something deeper is going on.

The dating app OkCupid, which is more popular among a slightly older, and perhaps more relationship-oriented cohort than Tinder, said in a blog post that since the start of the pandemic “connections and conversations across borders are up nearly 50% among singles, and people are setting their location preferences to ‘anywhere’ more than ever before.” More than 1.5 million users say they are open to a long-distance relationship, according to data from the dating app’s famous user questionnaire.

Dating coach and industry consultant Steve Dean said his clients have been more willing to widen their geographical perimeter during the pandemic.

“People bake into their baseline expectations the awareness that they probably won’t meet up in person anytime soon, which makes them feel much more comfortable messaging people from much further away and setting up virtual dates—everything from virtual tantra, to yoga, to deep conversations,” he said in an email.

Apps that combine dating and livestreaming, where you can interact with people all over the world, have seen a massive rise in streaming time.

Both Dean and Lemarc Thomas, founder of a matchmaking agency in Sweden, have had European clients who flew to meet someone in a different country despite the challenges and risk of traveling during the pandemic. Some people are realizing that they can work anywhere, be anywhere, Thomas said. “I’ve seen a lot of relationships that have blossomed that perhaps wouldn’t have started had it not been for corona.”

On the other hand, many people have relocated temporarily because they can’t afford rent. “Looking [for a relationship] just in the immediate neighborhood of where they happen to be right now doesn’t even make a ton of sense. And so they’re willing to look elsewhere,” Cook said.

The bigger picture

Dating companies love to emphasize that they have broken all sorts of barriers, like citing a well-known 2017 study which found a correlation between an increase in interracial marriages and the rise of online dating. In the same OkCupid blog post discussing the recent “borderless” trend, the company says that its daters “are 15% more likely to connect with users of a different religion than they were before the coronavirus outbreak—and people open to interracial relationships increased 10% during the pandemic.” Is geography one of the few remaining barriers?

How many people would actually follow through with meeting someone in a different location in a post-Covid world remains an open question. Sebastian is 24 and lives in Des Moines, Iowa. He used Passport several times both before and during the pandemic to check out the women on Tinder in Chicago and Omaha, a five and two hour drive away, respectively. But, he says, he did it out of boredom.

“It’s just fun to see what’s happening and other cities. I always like to look, and then I change my location back to where I am. Because I don’t actually want to match somebody who’s in another city, 500 miles away,” he said.

Eric Resnick, longtime online dating coach and industry consultant, is skeptical. “There used to be the joke like, ‘Oh, I’ve got a girlfriend in Canada,’” he said. “But now you can actually have your girlfriend in Canada, or London, or Saudi Arabia.” But, he wonders, how do you navigate a new online relationship? Are you exclusive, or do you also date locally? “There’s potential for it, but I think it’s inherently risky,” he said. “Nothing’s real until you’re in the same room at the same time as someone.”

While admitting it might be a “parochial view,” Resnick thinks that proximity is necessary rather than negotiable. “As I’ve seen, over time, with people just even in the US, trying to date people in other states, people get lonely, not having the person that’s supposed to love them next to them,” he said.

At the same time, geographic flexibility is often forced upon couples. Researchers suspect long-distance relationships are becoming more common. There are more couples where both people are pursuing high-powered or academic careers, which might require them to live in different cities.

The rise of long-distance relationships could also be an indication for greater societal instability, which was affecting people’s lives well before the pandemic. The 2008 recession pushed people to take jobs away from home, and the number of long-distance relationships hasn’t fallen, the Economist wrote in 2017. Recent research from the Pew Research Center confirms this: 47% of all Americans say dating is harder today than it was a decade ago. A third say it’s because they are too busy.

“I have a strong suspicion that our romantic relationships parallel our workplace relationships, and as our society trends more toward gig work and freelancing, with fewer stable career paths, our relationships will follow suit,” Dean, the dating coach, said. They may become less stable, and more loosely defined. “If I don’t know if i’ll be able to pay rent this month, or how much attention I’ll have to suddenly spend seeking my next gig, it’s hard to then turn around and promise the world to a romantic partner.”

Especially when your partner is a world away.