Meet the secretive electronic trading pool Goldman Sachs is considering dumping

No, Sigma X is not a Goldman Sachs fraternity. It’s the electronic trading platform the bank may be about to shutter (paywall), the Wall Street Journal reported yesterday. (People familiar with Goldman’s thinking tell Quartz that the firm hasn’t made any decision on the platform.)

No, Sigma X is not a Goldman Sachs fraternity. It’s the electronic trading platform the bank may be about to shutter (paywall), the Wall Street Journal reported yesterday. (People familiar with Goldman’s thinking tell Quartz that the firm hasn’t made any decision on the platform.)

Goldman uses Sigma X to help companies and hedge-fund clients sell big blocks of shares. Closing it wouldn’t be all that surprising, given recent events in the marketplace:

- Regulators including the Department of Justice have intensified their scrutiny of electronic trading and high-frequency traders in particular.

- After penning his latest novel Flash Boys, Michael Lewis created a relative storm of controversy on the Street by proclaiming the the markets “rigged.”

- Goldman president and COO Gary Cohn wrote an article in the Wall Street Journal backing curbs on HFTs, and the firm issued a memo supporting a Sigma X rival, IEX Group, featured in the aforementioned Flash Boys.

- Reports emerged that Goldman is in talks to sell its equity market-making unit, formerly known as Spear, Leeds & Kellogg, to a Dutch firm.

So here’s the short history of Goldman’s dalliance with Sigma X.

It launched the platform in 2006 with the idea of creating its own alternative trading system that could discreetly match buyers and sellers of big blocks of securities without widely publishing the bid and ask (i.e., the prices at which investors are willing to buy or sell a security). Such platforms are known as dark pools, because the orders are hidden from public view until they’ve been completed. They tend to exist outside traditional exchanges like the NYSE Euronext, though many of these exchanges now offer their own hidden buyer/seller matching business.

The merit of dark pools is that they allow a large company to place a massive order for shares without the rest of the market learning about its trading plans. Discretion is key because other traders, particularly HFTs, with knowledge of big orders can drive the price up or down before the original order can be completed. The downside of dark pools, critics argue (pdf), is that their secretiveness prevents the natural forces of supply and demand from determining the price of securities, as you would in a public forum.

Goldman launched Sigma X at a time when traditional exchanges like the NYSE dominated equity trading and there were few banks with their own dark pools. In 2009, the ranks of bank-run dark pools began to swell. Goldman launched two more of its own, in Hong Kong in 2009 and in Australia in 2012.

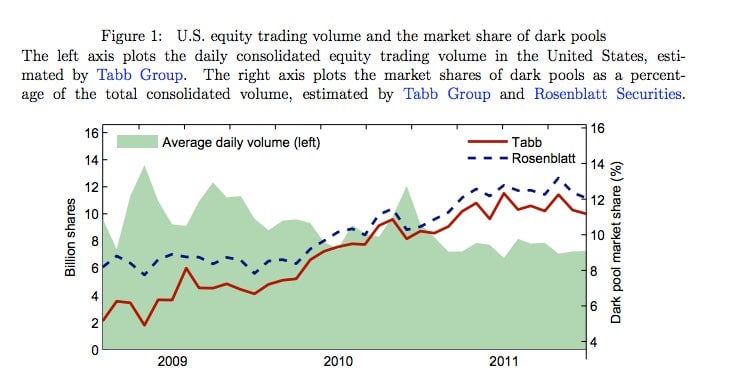

The dark pools’ share of the total trading volume on equity markets doubled from 6.5% in 2008 to about 12% by 2011 (see chart below). It’s now heading lower, and is likely to keep falling as firms like Goldman weigh the merits of keeping the businesses. Not only have regulators been sniffing around dark pools and electronic trading more intensely since the May 6, 2010 “flash crash,” but dark pools have become less profitable as more players have entered the mix and profits from overall equity trading have been declining.

Clues that Goldman might shrink its own dark pool operations came as recently as 2012, when it shuttered the Canadian arm of Sigma X less than a year after opening it. Incidentally, all the new competitors aiming to broker big trades for hedge funds and companies has made it less costly for big investors, who have multiple options from which to choose, and consequently the revenues from equity trading also have declined. That fact may also be one reason Goldman is mulling exiting the business, although insiders say it’s performing well. The bank declined to comment on its plans.