How TikTok stars are reinventing the path to fame

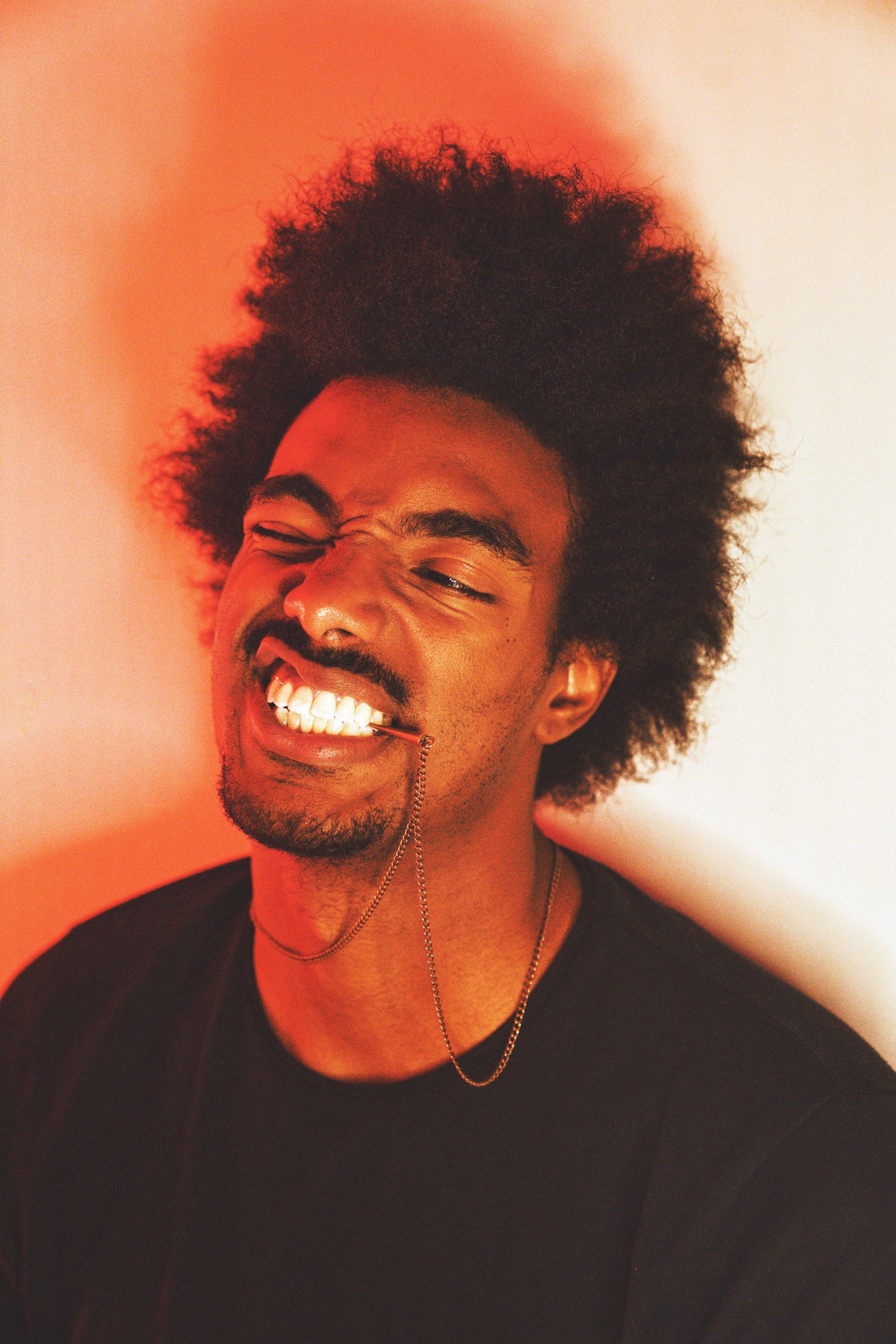

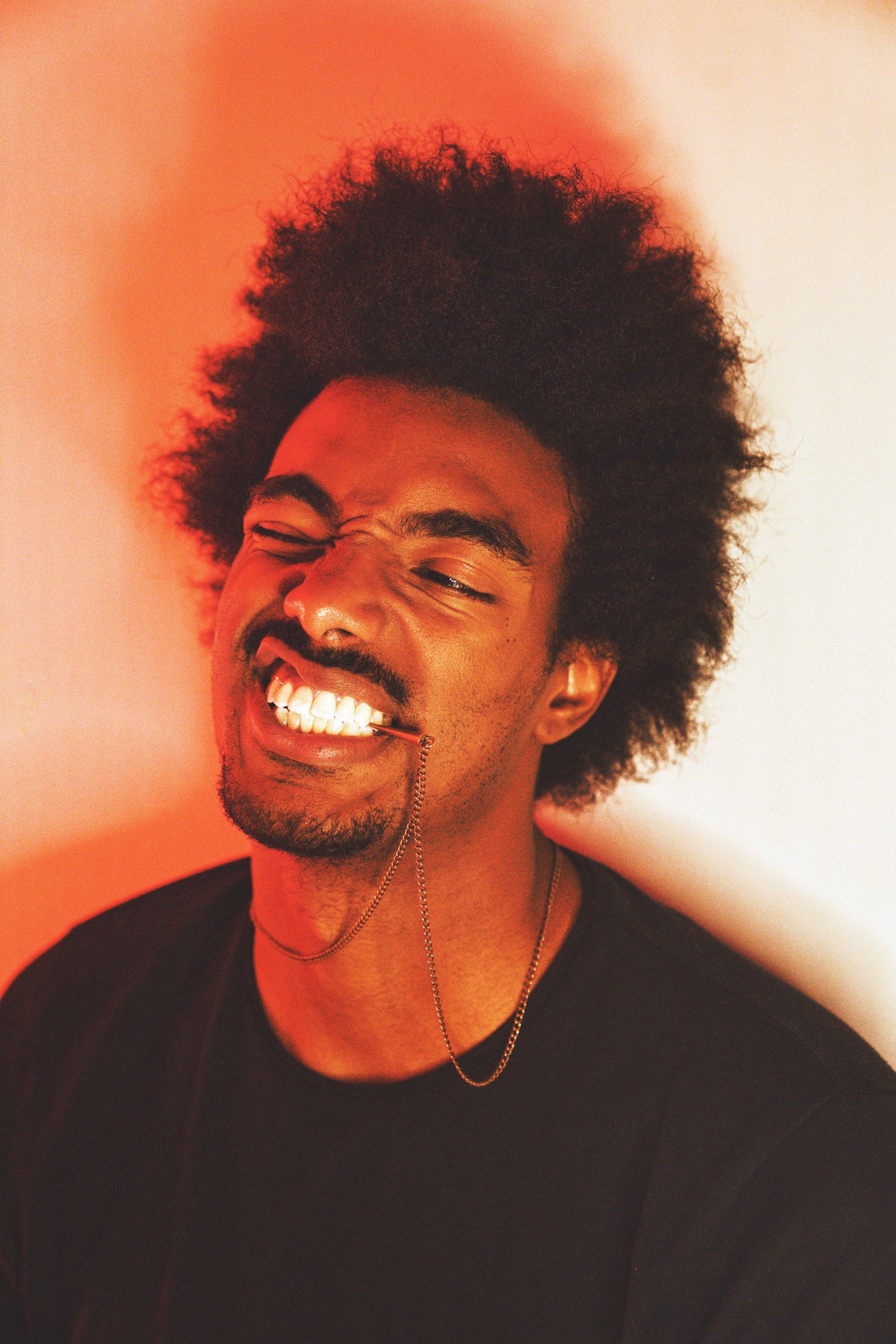

In May 2020, Tai Verdes had amassed a few things: multiple failed auditions for American Idol and The Voice, a job selling smartphones at a Verizon store, and a spot in a parking garage, where he practiced singing in his car for an hour-and-a-half every night. Most crucially, he had also tucked away a few lines of a catchy new pop song he’d been writing about a friends-with-benefits relationship. One evening, on a whim, he filmed himself behind the wheel while singing along to a demo of the track, and uploaded the short clip to TikTok.

In May 2020, Tai Verdes had amassed a few things: multiple failed auditions for American Idol and The Voice, a job selling smartphones at a Verizon store, and a spot in a parking garage, where he practiced singing in his car for an hour-and-a-half every night. Most crucially, he had also tucked away a few lines of a catchy new pop song he’d been writing about a friends-with-benefits relationship. One evening, on a whim, he filmed himself behind the wheel while singing along to a demo of the track, and uploaded the short clip to TikTok.

By Aug. 2020, as the Los Angeles resident was fielding multiple record deals from major labels, he had a little more in his corner: nearly 4.5 million streams of the song, “Stuck in the Middle”; the number-one spot of the Spotify Viral 50 chart; thousands of fan videos using his song on TikTok. He used all of this to negotiate a contract with Arista Records that gives him a level of creative control many established musical stars would envy—and he gives the credit to TikTok.

“I didn’t have a part in the old music industry at all. It was me doing stuff and no one listening,” said Verdes, 25. “Then TikTok made people listen.”

TikTok boasts plenty of stories like Verdes’: young, ambitious artists who parlay a hit on the app into a foothold in the mainstream music industry. Arguably the most famous, rapper Lil Nas X, followed his “Old Town Road” to a deal with Columbia Records, two Grammys, and consecutive Super Bowl commercials. And while it’s not a new path for an artist to go viral and sign to a big label—many did the same on Youtube, Vine, and Instagram—the volume of TikTok musicians grabbing that brass ring is notable: More than 70 TikTok-famous artists were signed to major labels in 2020 alone.

The specifics of Verdes’ deal with Arista, however, further defy the “old music industry,” and how young artists are harnessing their online popularity to dodge some of its most common trapdoors.

🎧 For more intel on music industry trends, listen to the Quartz Obsession podcast episode on disco. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.

Instead of signing a lengthy, multi-album deal with a major label—which generally used to be the goal of a new, hungry artist—Verdes and his management took a different approach: They secured a short-term arrangement that covers just one release and assures him full, long-term ownership of his masters. Verdes will release one EP in late spring with Arista and receive a net profit split of its proceeds, after which he can renegotiate or walk. Essentially, he agreed to license his IP to a label, not sell it outright—a rare level of artistic control for any artist on a major label. (Rihanna, U2, and Jay-Z are also members of this small club. Verdes’ hero, Frank Ocean, also owns his masters but left the major-label system, as did Garth Brooks and Ciara.)

Verdes had good reason for his apprehension with the traditional long-term label contract: The music industry has long been known for pushing deals on new artists that fleece them financially and heavily restrict their creative freedom. In the 1960s and ‘70s, Motown Records was infamous for creatively restricting and shortchanging its artists, despite their enormous record sales and airplay; Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones, TLC, and many more marquee artists publicly protested their labels’ miserly contracted royalty payments after the artists released hits. Prince battled his label, Warner Bros., for many years for their ownership of his masters and other creative restrictions; his many public protests included scrawling “slave” on his cheek, changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol, and warning other artists, “If you don’t own your masters, your master owns you.” More recently, Taylor Swift made headlines for fighting unsuccessfully for her masters, and decided to re-record her songs.

So for Verdes and his team to negotiate otherwise is notable—and not accidental. He points to his independently grown online fanbase as his primary bargaining chip.

“TikTok gives you leverage as an artist, which is something artists back in the day didn’t have,” said Verdes. “You didn’t just have a 50-million-stream song out of nowhere. So now you don’t have to do those old deals where you have to sign away four albums and they give you a $2 million [advance] that you have to pay back anyway. I knew I wanted to own my intellectual property and to have a short-term deal, because that gives me more power.”

Verdes isn’t the only TikTok star walking away from more dollar signs upfront in the hopes of greater artistic integrity, not to mention future paydays. Curtis Waters, another star on the platform, went viral in 2020 for his pop-rap track “Stunnin’” and promptly passed on several major label offers; as he later told Rolling Stone, “I came so far independently. I’m not sure the major labels are giving artists what they really need.” He eventually signed with the label-and-publisher hybrid BMG in exchange for a 60-40 profit split and control of his masters, a similar deal to Verdes’. Other TikTok artists have gone viral and chosen the more autonomous routes of releasing individual tracks instead of EPs or albums and licensing their songs to advertisers and other media; many also partner with brands to create sponsored content on their TikTok pages. (This “influencer” model is more prevalent on Instagram but growing steadily on TikTok.)

Critical to Verdes’ rise, too, was his strategy for growing his fan base online: As “Stuck in the Middle” amassed streams on Spotify and video creations on TikTok, Verdes posted near-daily, conversational videos in which he updated his followers on new benchmarks, showed them around his Verizon store and modest bedroom, and made up cartoonish dance moves and silly walks. His personality was at the forefront alongside his song. And interspersed with the intimate footage was shrewd marketing: When Spotify streaming data showed that 87% of listeners of “Stuck in the Middle” were men, Verdes posted a video asking his male fans to play the track for women; the song’s demographic quickly jumped to 33% female.

“In many cases, a song goes viral because of a trend, but Tai was part of the trend himself. He wasn’t starting a dance [fad], he was talking about his song,” said Brandon Epstein, one of Verdes’ managers. “We’d never seen anything like it before.”

Verdes continues to post regularly on TikTok, including motivational posts to other musicians aspiring to his trajectory. As he approaches the recording of his EP, he has this note of advice to all would-be stars:

“Never even think of signing a deal unless you have leverage of some sort. Especially with TikTok, now you can bust out 20,000 streams if a video does half good,” he said. “Building yourself up has become expedited because of TikTok. So try longer on there. If it doesn’t work, then your song’s not good enough. And if it works, guess what? Your song’s good enough, and you’re off to the races.”