The app behind virtual Burning Man wants to host your next office function

Last April, the organizers of Burning Man—the anything-goes music festival that typically draws 80,000 attendees for a week of communal living in the Nevada desert—canceled all in-person revelry because of the pandemic. Instead, the September festival was hosted virtually, in a week of events spread across eight digital platforms, including a nascent video chat service called Topia.

Last April, the organizers of Burning Man—the anything-goes music festival that typically draws 80,000 attendees for a week of communal living in the Nevada desert—canceled all in-person revelry because of the pandemic. Instead, the September festival was hosted virtually, in a week of events spread across eight digital platforms, including a nascent video chat service called Topia.

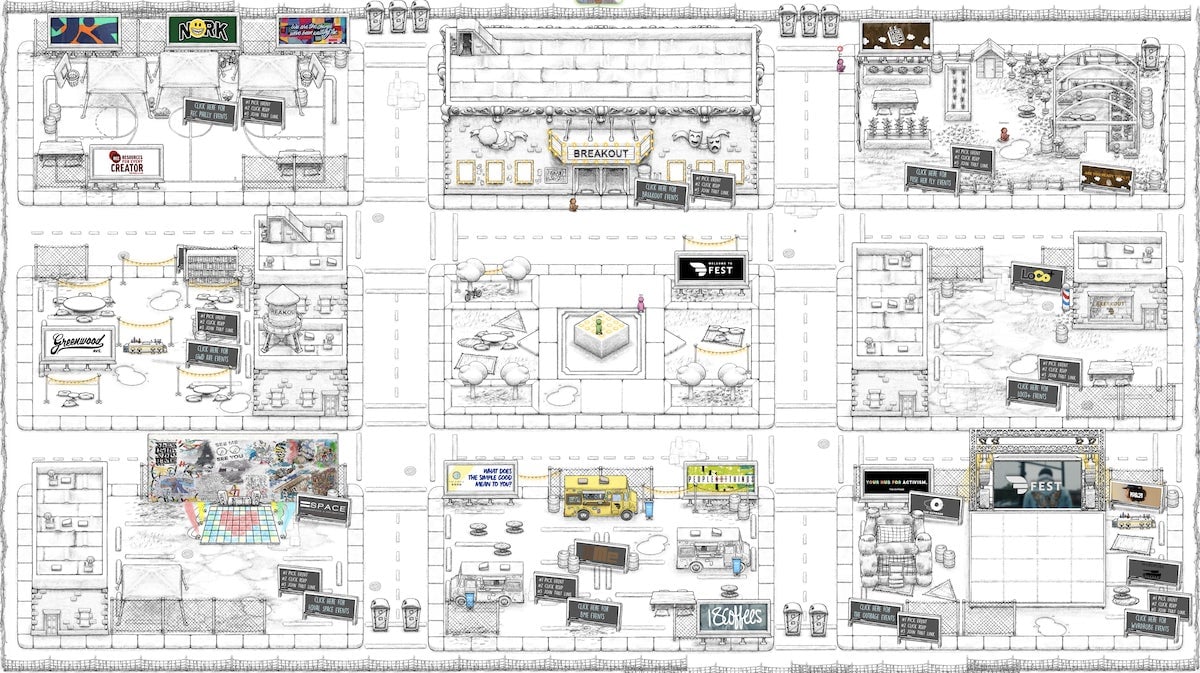

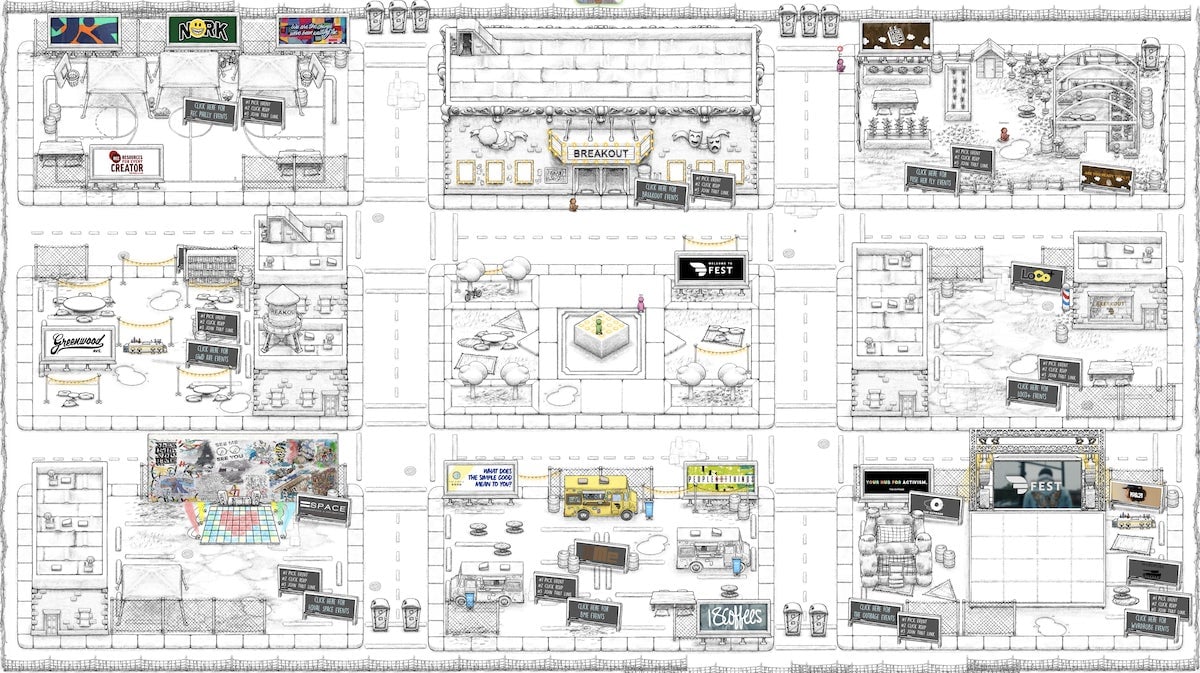

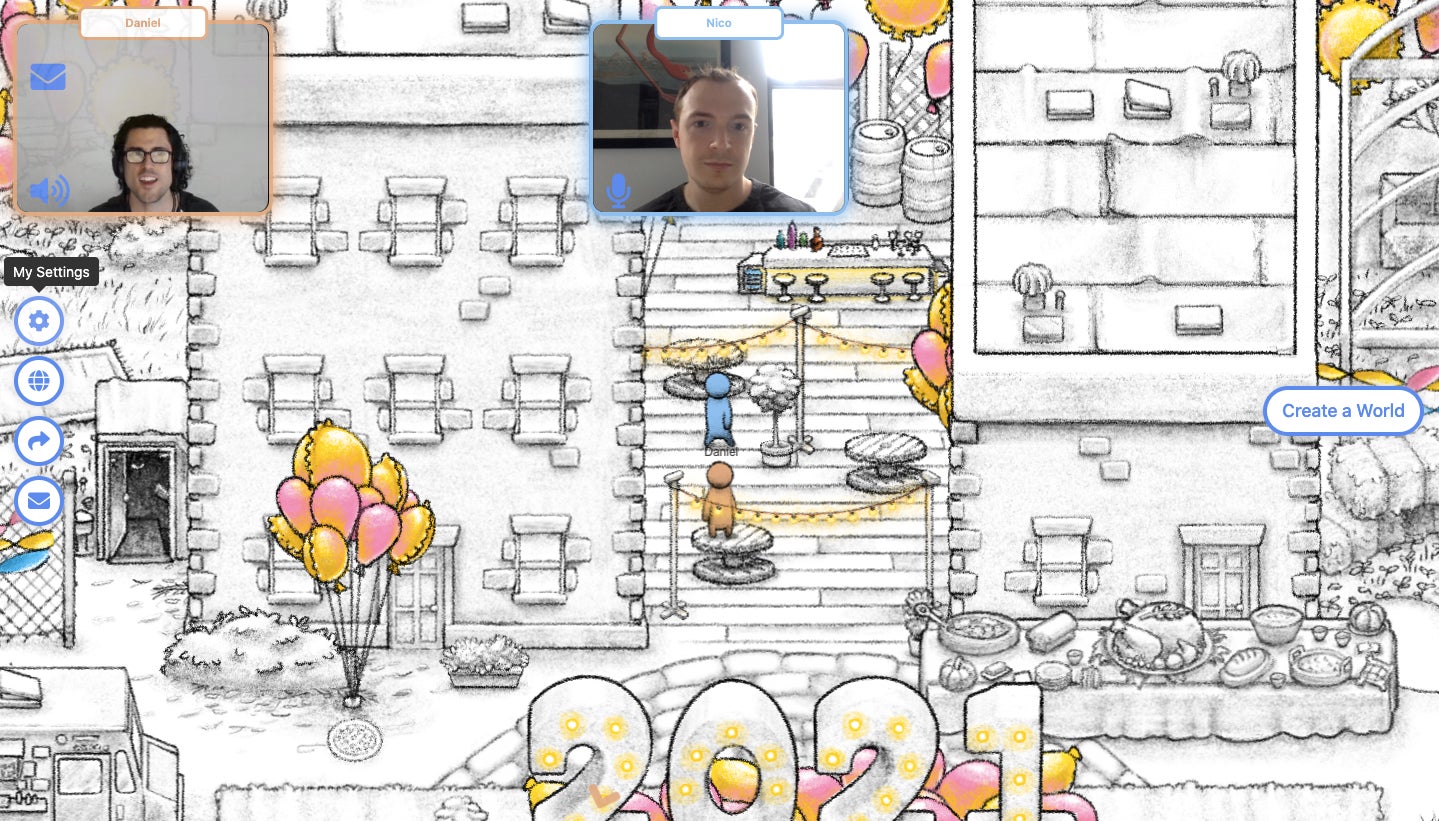

Topia allowed would-be Burners to build virtual versions of their festival campsites. Instead of dragging power tools, plywood, and rebar into the desert, they dragged illustrations of tents, concert stages, and port-a-potties onto a digital canvass. Each user, represented by a simple avatar, could walk around, explore a vast map of other user-generated campsites, and chat with the virtual attendees they met there.

The app wasn’t built for Burning Man—it coincidentally launched in June, and its founders were former Burning Man attendees who tossed their hat in the ring when they heard the festival was looking for a digital home. But the festival served as both a grand opening and an early test for Topia, which hosted about 16,000 visitors and 500 camps during the week.

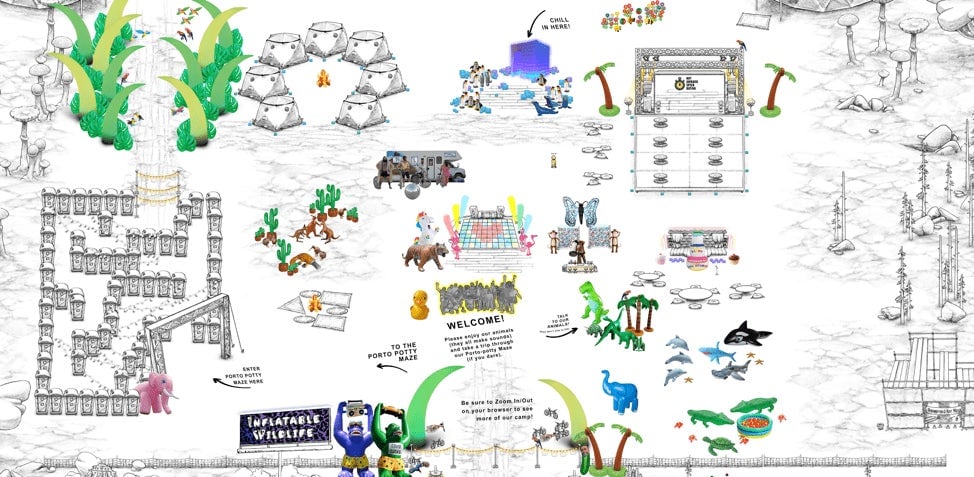

Now eight months old, Topia bills itself as a more sociable alternative to Zoom, and is one of many startups racing to create more realistic social experiences online. The pandemic has created a booming market for this kind of technology in the workplace—indeed, Topia CEO and co-founder Daniel Liebeskind hopes companies will use the platform to create a social outlet for their employees that feels a bit less stilted and and awkward than typical virtual happy hours. But he also has ambitions for the site that extend far beyond the office.

The future of virtual events

Bryan Aldea, who had been planning to make his fifth straight pilgrimage to Burning Man last year, decided to give the virtual iteration a shot. Normally, he and his friends would lug a menagerie of blow-up animals into the desert and turn their camp into an “inflatable wildlife safari,” which other attendees could stop by and visit. This year, a Topia developer who had heard about their camp asked if they would make a digital version of it for the online festival.

The site lends itself to organic interaction: When your avatar gets close enough to another person’s, you can hear their voice and see their face in a small video feed. That mechanism allows users to recreate many of the social conventions that usually get lost on video calls: Instead of having one person talk while everyone else listens, people can splinter off into smaller groups, pull a friend aside to catch up one-on-one, or mill about until they find someone to talk to.

“It turned out to be a really great experience,” Aldea says of virtual Burning Man. He acknowledged it didn’t have quite the same thrill as the real-world experience of watching a hulking, 75-foot (23-meter) sculpture burn to the ground. But even so, he said: “You don’t necessarily have to have a physical event to enjoy the same camaraderie, the same kind of connections that you have with people.”

That’s exactly the kind of virtual connection many companies are looking to foster as offices remain closed amid Covid-19. Businesses, nonprofits, schools, or any other type of organization can pay Topia $5 per month to create a world where an unlimited number of people can mingle anytime.

Topia’s virtual Burning Man was free, but future large events will be ticketed. Topia charges event organizers $2 per person per day for gatherings of more than 25 people. Organizers then have the option to charge attendees an entrance fee.

Virtual real estate

Liebeskind is even more excited about getting into the digital “real estate” business. Topia’s CFO is John Zdanowski, who from 2006-2009 was the CFO of Second Life, a virtual world experiment from an earlier era of the internet. (You might remember the gag in The Office in which Dwight Shcrute insists Second Life is not a game.) In its 2009 heyday, Second Life boasted an internal economy worth $567 million.

Linden Labs, the company that developed Second Life, raked in as much as $100 million a year by parceling out “real estate” (essentially, server space that could host vast tracts of virtual land). Players would buy it and then, much like real-life real estate developers, customize the space and sell it at a premium to other players. The trade minted at least one millionaire. In 2009—while the actual real estate market tanked—Second Life brokers cashed out $55 million by converting in-game currency to US dollars.

At a recent Topia-hosted panel on the so-called “surreal estate” market, Zdanowski said Topia could take up Second Life’s mantle. “Sixty percent of [Second Life] revenue came from profitable in-world businesses, and I think Topia has the opportunity to enable the same thing,” he said. Zdanowski noted that Topia has a number of advantages over its predecessor: It doesn’t require you to download anything, you don’t have to create an elaborate fictional character to participate, and it came about in a moment when people are much more comfortable with the idea of hanging out in a virtual space.

While creating a basic world in Topia is free, the startup already charges users $9 per month to claim a personalized URL and access extra features. Liebeskind says Topia is also building an internal marketplace where users can buy custom-built worlds or sell their services as virtual architects. “One of the dreams here is what if artists and creative types can actually make a living where they’re creating art to facilitate human connection?” he said.

For now, that’s still a pie-in-the-sky dream. Topia isn’t bringing in revenue anywhere close to what Second Life did in its golden age. But users have begun to trickle in—Liebeskind said visitors created 1,700 worlds in December. One couple hosted their wedding on the platform. Topia has its own server on the chat and voice messaging app Discord, where diehard members share their latest creations—a model of the solar system that plays the sounds the Voyager satellites captured while whizzing by each planet, a very introspective game of Chutes and Ladders, a psychedelic forest buzzing with trippy music and lectures from the likes of Timothy Leary.

“You can see the excitement and the energy that creative types have for figuring out how to create spaces that bring people together,” Liebeskind said. “It’s really a beautiful thing.”