It’s not just southern Europe—Sweden is also fighting the deflation trap

Compared with the rest of Europe, Sweden’s economy is doing pretty well. Growth this year is expected to come close to 3%, making it the fastest-growing economy in western Europe.

Compared with the rest of Europe, Sweden’s economy is doing pretty well. Growth this year is expected to come close to 3%, making it the fastest-growing economy in western Europe.

So why are there so many concerned faces in Stockholm policymaking circles today? It’s because Sweden is struggling with a problem more commonly associated with Europe’s beleaguered periphery: deflation.

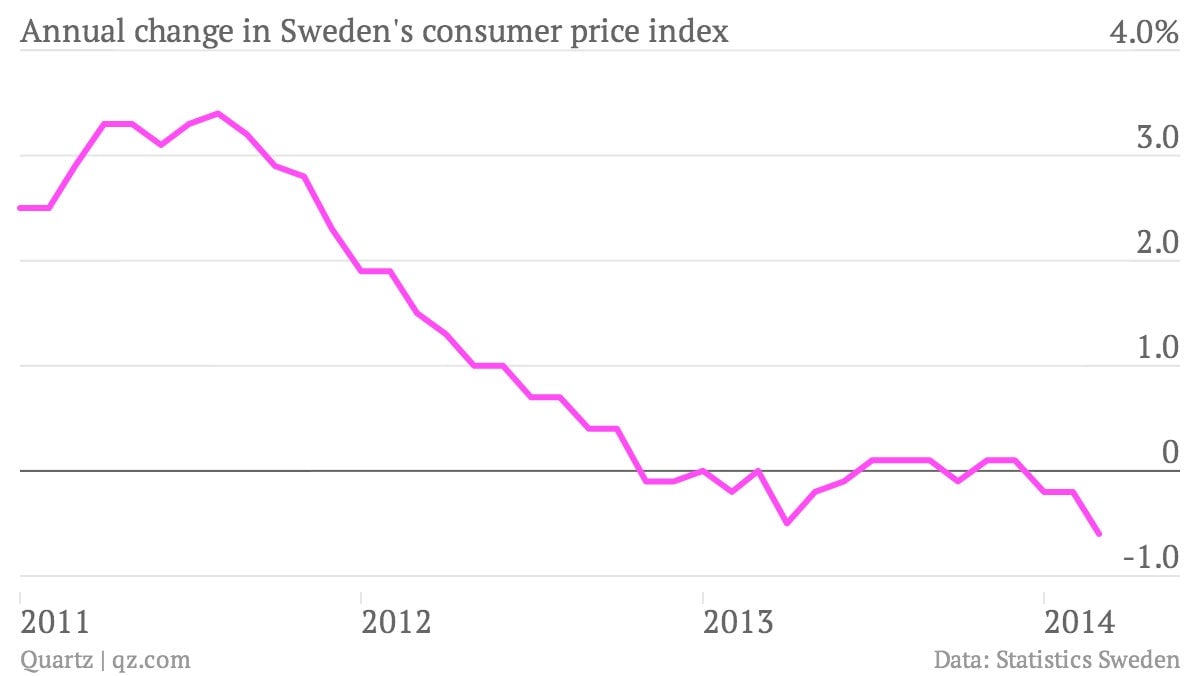

Consumer prices in Sweden fell by 0.6% in March, much more than expected. Although Sweden has been flirting with deflation for the better part of a year, this is the steepest drop since the depths of the global recession.

The central bank’s preferred measure of “underlying” inflation, which strips out the effect of mortgage rates, has not yet dipped into negative territory. This inflation gauge was flat in March, which matches its all-time low, last seen in 1998.

Two months ago, the Swedish central bank was confident that faster economic growth would soon push prices up, so it reckoned it would start raising interest rates early next year. After its meeting yesterday, which came before the latest inflation data were released, it changed its tone. The bank now thinks it is more likely to cut its benchmark rate, currently 0.75%, sometime in the coming months. Torbjörn Isaksson, an analyst at Nordea, notes that the latest data showed “many surprises across the board” and thinks a rate cut is coming this summer.

The tricky thing for Swedish policymakers is that lower interest rates may encourage more borrowing—and the country’s households are already some of the most indebted in the advanced world. Unlike the rest of Europe, bank lending has been growing at a healthy clip. There’s talk of a housing bubble to boot.

Stoking inflation by lowering interest rates would help erode Swedes’ large debt burden, but only if they stop adding to it. Thus, the focus on fighting deflation instead of indebtedness means that Swedish policymakers will hope that their countrymen have already taken on as much debt as they can stand. Signs that the housing market is finally cooling are encouraging in this regard.

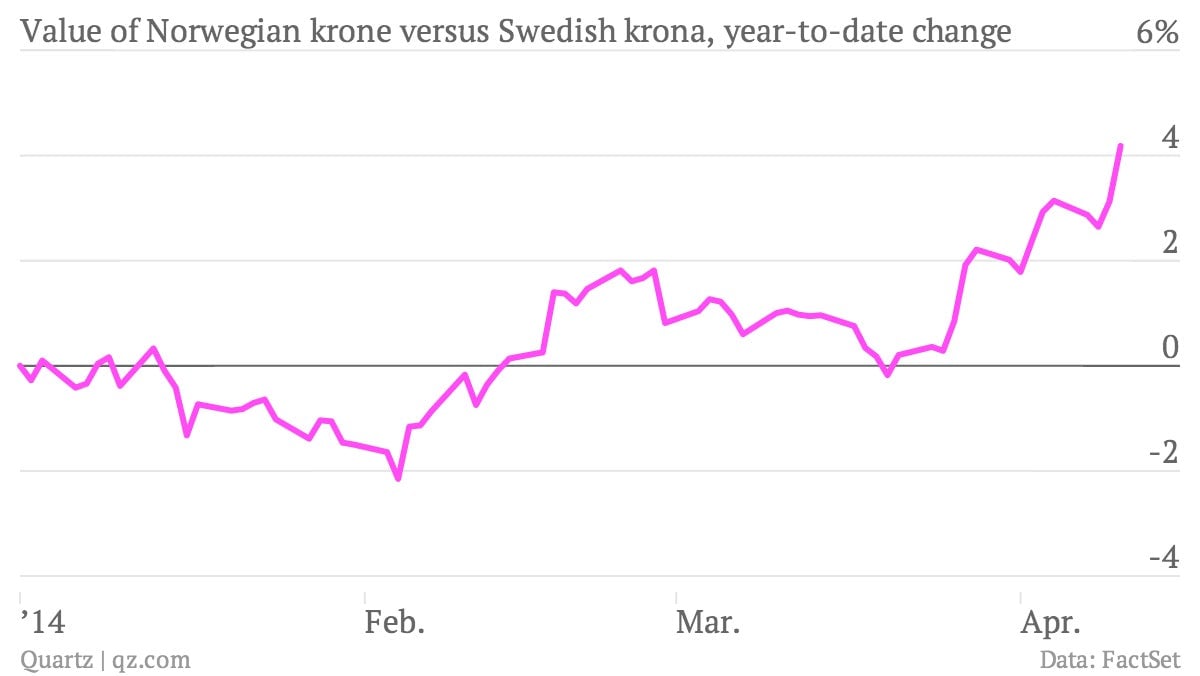

The policy shift’s most immediate impact has been on the value of the Swedish krona. The prospect of lower interest rates has seen the value of the krona sink against the currency of neighboring Norway.

One of the groups likely to cheer Sweden’s newfound determination to fight deflation will be Norwegian shoppers. The increasing purchasing power of Norwegians’ money across the border from their notoriously expensive country will make bargain-shopping in Sweden even more enticing. That could provide an extra boost to the Swedish economy and, eventually, reverse the worrying fall in prices that is proving so hard to shake.