One election strategy in India’s most populous state—make Muslims and Hindus hate each other for votes

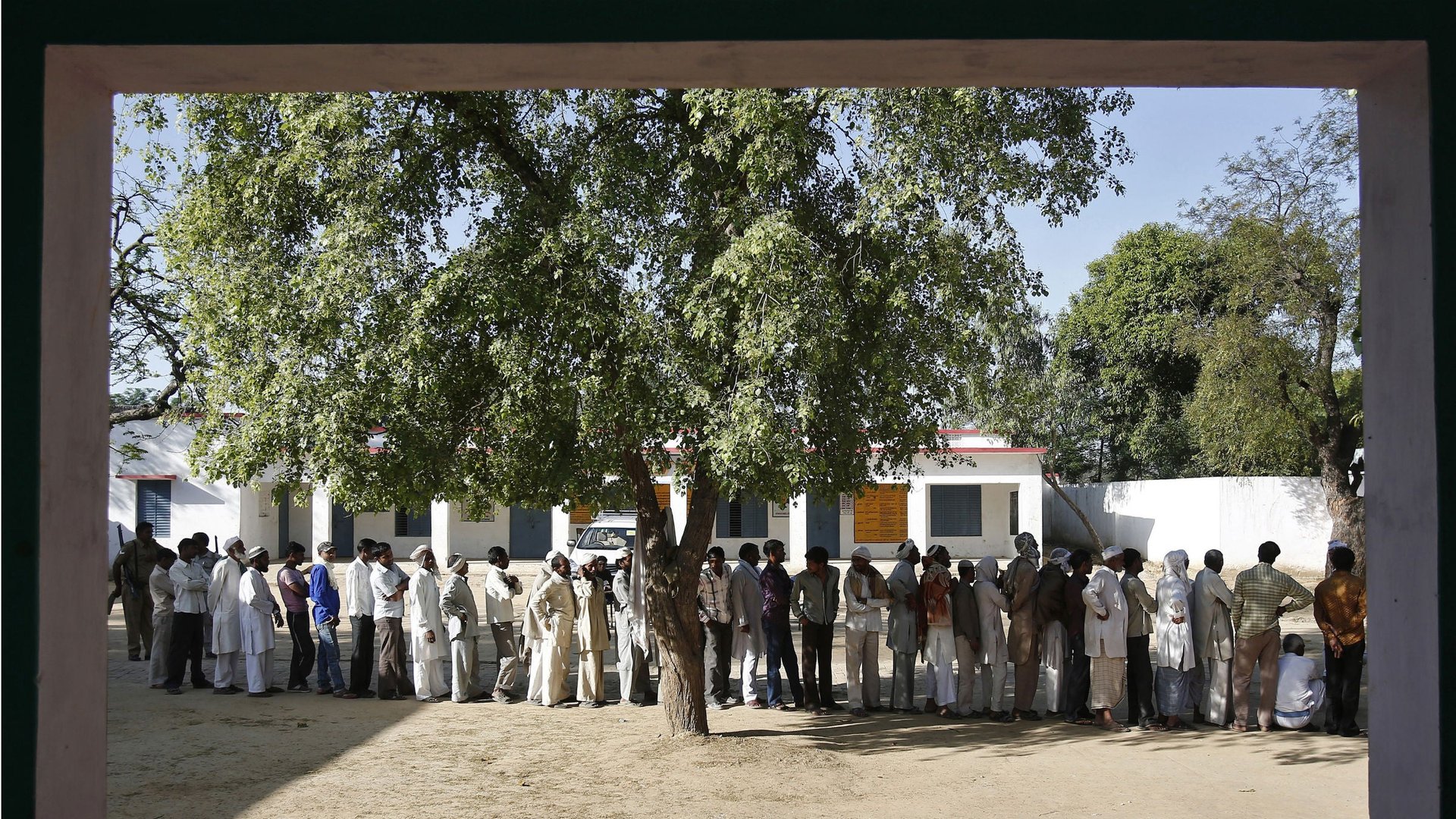

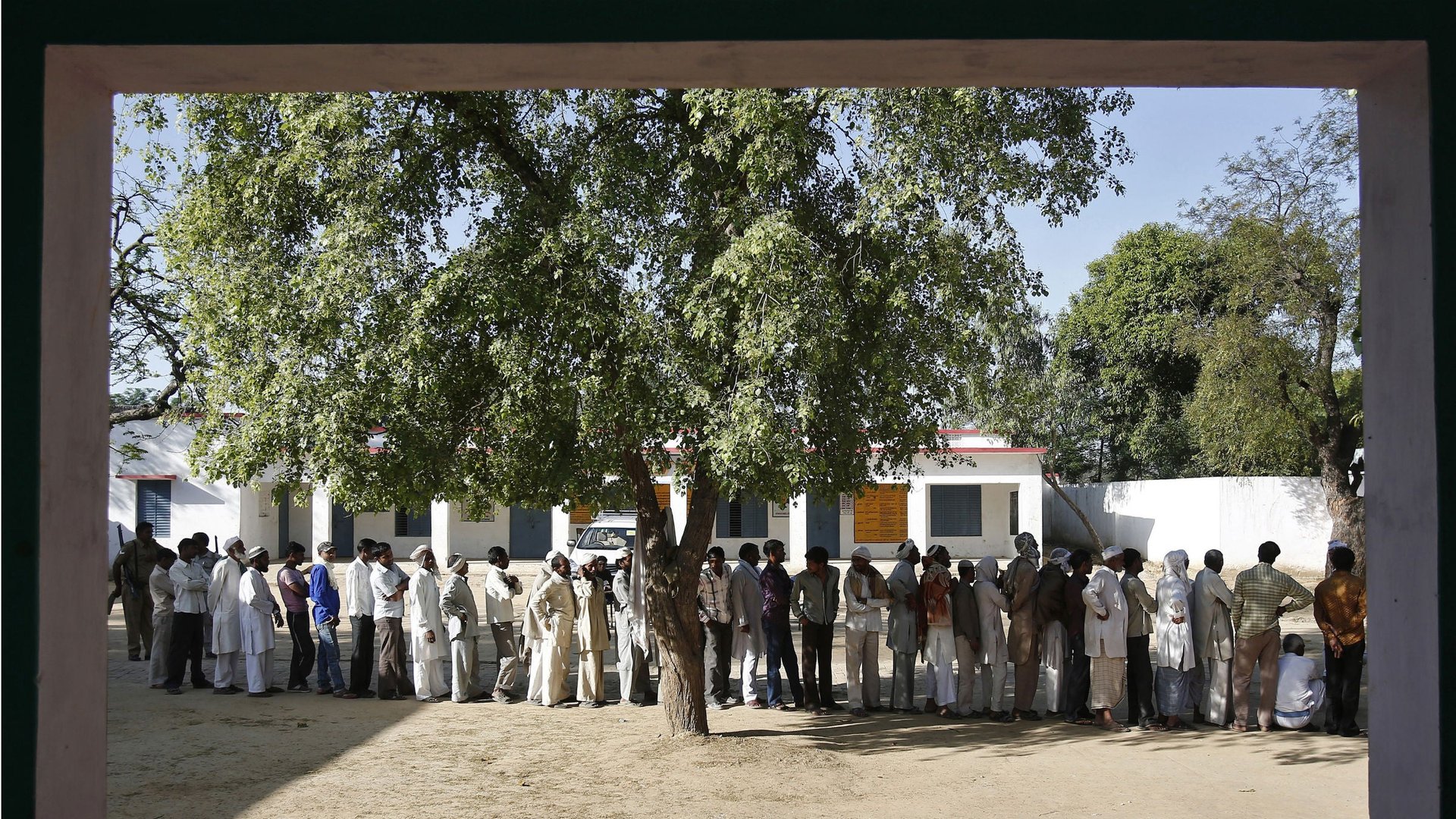

Muzaffarnagar, a western district in the massive Indian state of Uttar Pradesh that went to the polls on Apr. 10, is an excellent example of one of the ugliest truths of the world’s largest democracy—politicians regularly exploit religion to divide the electorate and win votes.

Muzaffarnagar, a western district in the massive Indian state of Uttar Pradesh that went to the polls on Apr. 10, is an excellent example of one of the ugliest truths of the world’s largest democracy—politicians regularly exploit religion to divide the electorate and win votes.

In Sep. 2013, religion-based violence, allegedly encouraged by local politicians, erupted in the villages of Muzaffarnagar and its neighboring district of Shamli between Jats, a Hindu caste that includes many owners of large sugarcane fields, and Muslims, who are predominantly laborers, carpenters and traders. More than 60 people were killed and tens of thousands of Muslims were displaced.

Since then, politicians have relied on the communal riot to worsen the divide and gain votes. India’s population is 80% Hindu, but the country was founded on the principal of secularism, and the constitution guarantees all the freedom to practice the religion of their choice. Still, clashes between religious groups, particularly Hindus and Muslims, spring up with alarming frequency, despite the fact that individuals from these communities often live side-by-side for generations.

Here’s how politicians continue to stoke the fires of dissent in Uttar Pradesh:

A week before voting day in western UP, Amit Shah, the top political aide to Narendra Modi, the Bharatiya Janata Party’s candidate and likely next prime minister of India, delivered an incendiary speech to 400 to 500 Jat men.

Unlike Modi, who has been very careful not to recall any religious-based incident during his campaign, tainted as his career has been by Gujarat’s 2002 riots, Shah said that especially in western UP, the election was going to be for “honor and to take revenge against insult and it’s an election to teach a lesson to those who have done injustice.”

It’s not just the BJP, though. A few days later, Azam Khan, the Samajwadi Party (SP) urban development minister in the UP state government, said during an April 7 rally that it was Muslim soldiers, not Hindus, who won the 1999 Kargil war against Pakistan. ”There was no Hindu who conquered the peaks of Kargil, but the peaks of Kargil were conquered by the Muslim soldiers, who said ‘Allah ho Akbar.'”

Two days later, Khan said at another rally that Muslims must vote to “show the fascists their worth and status and today you have to take revenge on the murders of Muzaffarnagar, and today you have to press the button and take revenge against the atrocities of 2002 in Gujarat.” Over 1,000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed in the Gujarat riots.

On Apr. 11, the Election Commission banned both Khan and Shah from holding public rallies, and called for criminal complaints to be registered against them. The commission said that their statements were made with “deliberate and malicious intention of outraging the religious feelings and religious beliefs,” and also criticized the state government of not even issuing complaints against the men.

Khan has been charged with “promoting enmity between different groups on ground of religion” and “deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs.” Shah has been charged with “promoting enmity between classes in connection with the elections” and “disobedience to order duly promulgated by public servant.”

But it gets worse.

Political parties in Muzaffarnagar don’t kick out people accused of inciting violence, they put them on the ticket. Two candidates who ran from Muzaffarnagar on April 10 face charges linked to the religious violence in September—Sanjeev Baliyan, the BJP candidate, Kadir Rana, the candidate from the Bahujan Samaj Party.

Seven months after the riots, villages that have been mixed for generations no longer have Muslims, who fled and have settled closer to other Muslim villages. The air is toxic with anger and sadness on both sides.

When I was there on polling day, instead of talking about western UP’s issues, such as bad roads (some of the worst in the country), criminality or corruption, Jat-Hindus and Muslims alike spoke of voting for the party that would protect them—the same parties that encouraged their divide in the first place.

“We don’t care about the roads. Lets talk about protecting people first and the SP has always protected us,” said Mehndi Hassan, 60, whose family is building a new house close to a Muslim village with the money he has received as compensation after the riots.