I started researching prostate cancer and scared the hell out of myself

Like most hospitals, the Manhattan campus of the New York Harbor VA Hospital is laid out like an intestine, and it operates about as fast as one. At the security checkpoint, where the X-ray scanner was broken, three security guards chatted and passively watched the line grow while a fourth wand-frisked and bag-checked people, one-by-one. I walked through the main lobby, where I have in the past spent minutes waiting for one of the eight elevators to show up. Today I was lucky because I only had to walk down one, short, low-ceilinged hallway to get to a clinic on the ground floor.

Like most hospitals, the Manhattan campus of the New York Harbor VA Hospital is laid out like an intestine, and it operates about as fast as one. At the security checkpoint, where the X-ray scanner was broken, three security guards chatted and passively watched the line grow while a fourth wand-frisked and bag-checked people, one-by-one. I walked through the main lobby, where I have in the past spent minutes waiting for one of the eight elevators to show up. Today I was lucky because I only had to walk down one, short, low-ceilinged hallway to get to a clinic on the ground floor.

I wasn’t looking forward to having my prostate checked. I’ve lived in New York for two years, and I’m still only barely comfortable with strangers on a subway touching the outside of my body, let alone with having a physician I’ve never met insert a lubricated and gloved finger into my rectum.

For many men, prostate cancer is inevitable. I’m an American male, which means I have a one in seven chance of getting the disease at some point in my life. But I’m not afraid of tumors, even after growing up watching my mom fight them. Cancer itself is too abstract to scare me into visiting my doctor. The treatments for prostate cancer, however, are terrifying. They are full of radioactive or ice-filled needles, catheters that slither up the inside of your penis, and scalpel-tipped tentacles that excise your afflicted cells by worming their way through holes in your belly.

Down the prostate cancer rabbit hole

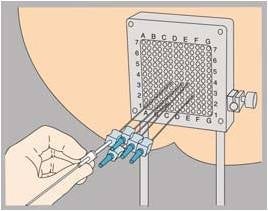

It all started a few weeks ago. I was researching a story on low-dose radiation brachytherapy, a treatment for prostate cancer that kills relatively mild tumors with strategically-placed radioactive pellets. This is how those pellets find their way to your prostate:

If the anatomical clues in this picture are too subtle, let me explain. The grey square is called the grid. It is placed along your perineum—the area between the scrotum and rectum. Your genitals are taped to your belly, because the doctor needs unrestricted access as he guides 20-25 metal needles into your prostate, about four-inches deep. Inside the needles are about 60-120 of the pellets that he’ll strategically place around your tumor, using imagery from a rectal ultrasound probe (not pictured) to guide himself. If you’re starving for more detail, click here (Warning: graphic.)

The pellets will stay in your body for about six months, emitting a low dose of radiation that breaks down the cancer cells’ DNA until they are too flawed to replicate. It’s considered one of the better ways to treat low-risk tumors because the recovery time is quick, and patients are unlikely to wind up impotent or incontinent after the procedure. The more I researched, the more nervous I got. Finally I called the clinic and made an appointment for a regular physical check-up. They didn’t ask why I wanted one, and I didn’t tell them.

What is a prostate and how does it get cancer?

The prostate is a small (“walnut-sized” seems to the usual term) gland. Its main job is creating a slippery enzyme, called prostate specific antigen (PSA), that helps sperm loosen up for the Big Swim. It also gives them some sustenance in the form of zinc, fructose, citrate, and selenium. “It lets your semen get very runny, then very sticky, then very runny again,” explains Dr. Sean Cavanaugh, a radiation oncologist from the Cancer Treatment Centers of America at Southeastern Regional Medical Center in Georgia. “It’s only good at manufacturing a fluid to knock somebody up. That’s it. It’s not involved in arousal, libido, erection, sensation of climax.”

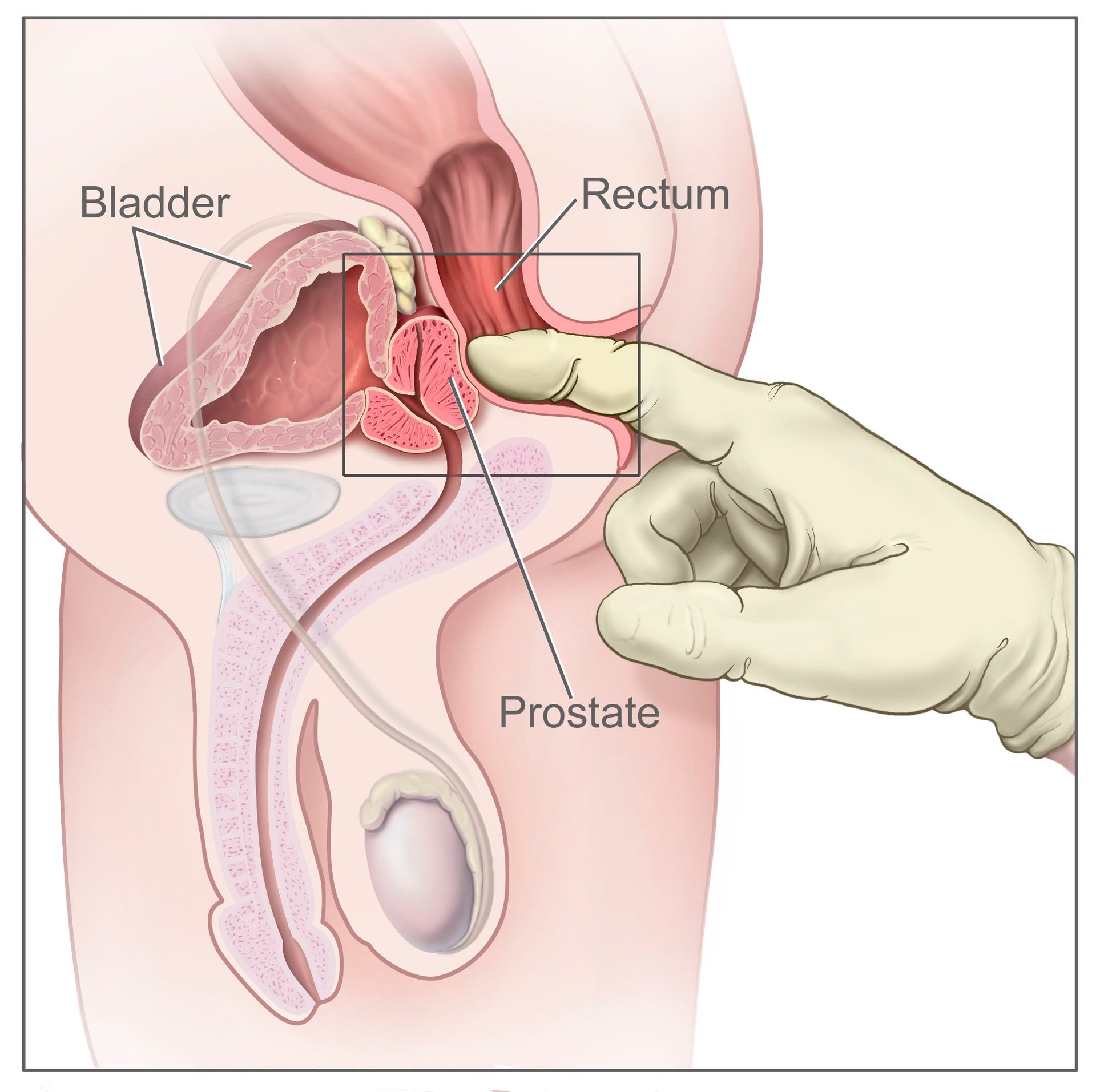

The prostate itself may not be involved in these things. But it’s nestled cozily amid body parts that control fornication, urination, and defecation. This biological intimacy can make treating prostate cancer a tricky and dangerous business.

Nobody knows for sure what causes prostate cancer, but we do know what happens once the cancer hits. The prostate, like everything in your body, is made out of cells. Cells replicate. Before they do, enzymes called polymerases crawl along the DNA, proof-reading it for errors so they don’t get passed along to the copies. But cancer cells don’t proof-read. “Cancer cells are obsessed with reproduction,” says Cavanaugh, “They don’t check the DNA for errors, they don’t repair errors, and they tend to accumulate genetic damage.”

In a small number of men the cancer barely grows at all, and they will never have to experience the treatments you’re about to read about. In the rest, if it’s left untreated, the cancer will probably spread within the prostate, leaving the microscopic tissue looking like a used Kleenex. (Doctors grade the cancer’s severity based on how ragged the tissue is using something called a Gleason Score.) It might spread to other nearby organs and glands, like your bladder, rectum, or the seminal vesicles. Eventually the cancerous cells disrupt the normal functions of the organs and glands, and things start shutting down.

Back in the hospital, I stepped up to the desk and waited for one of the several nurses staring at computer screens to summon me. “How can I help you,” one of them said, without looking up. I resentfully told her my name and social security number, and she resentfully checked me in. Though I was 30 minutes early, I still had to wait for an hour. During that time, people came and went, but besides the nurses, I was the only person too young for prostate cancer.

I was comparing notes with another waiting-room refugee when I heard my name called. The doctor introduced himself and greeted me with a compliment on how good my blood pressure was. I followed him to his office, and we eased into the “first dance” portion of the physical. Was I allergic to anything? Did I smoke? What about exercise?

I cleared my throat and told him the real reason I was there. Yes, I was young, fit, and healthy, but learning about brachytherapy, I explained, had turned me into a wreck. The next thing he said was hardly reassuring: ”There’s no good screening process for prostate cancer.” From there he launched into an explanation of the risks. His demeanor settled the bubbling in my stomach to a simmer, but I was still nervous about the looming main event.

What are the odds?

There are three things for a man to know about prostate cancer risk:

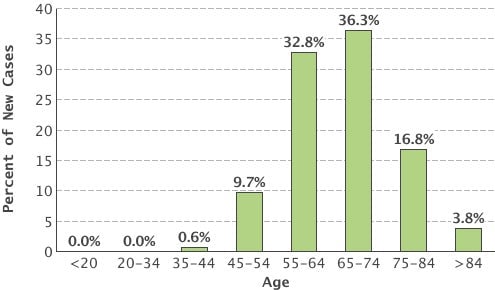

1. As you age, your odds of having a cancer-free prostate get pretty slim. The chart below, showing new diagnoses by age, shows how the overall one in seven lifetime risk bears out for different age groups. It’s important to note that your risk of prostate cancer doesn’t actually go down after 74, it’s just that most men are diagnosed earlier.

2. If men in your family have had prostate cancer, odds are you will as well. Studies disagree on exactly how much your chances increase, but exactly how much is unsure. The following are estimates of how different relatives with the disease affects your chances:

Family history and prostate cancer risk

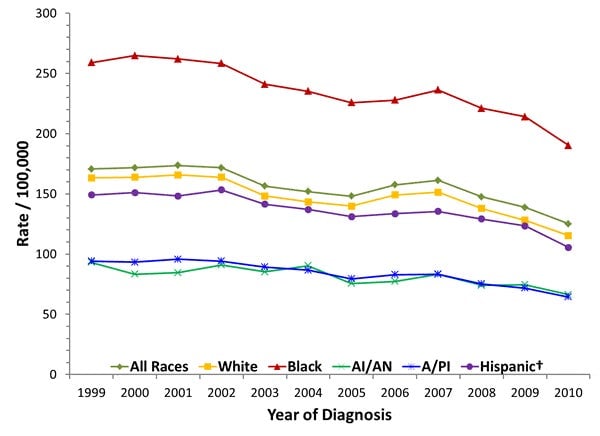

3. If you are African-American, you are more than twice as likely to get prostate cancer as any other race in the US.

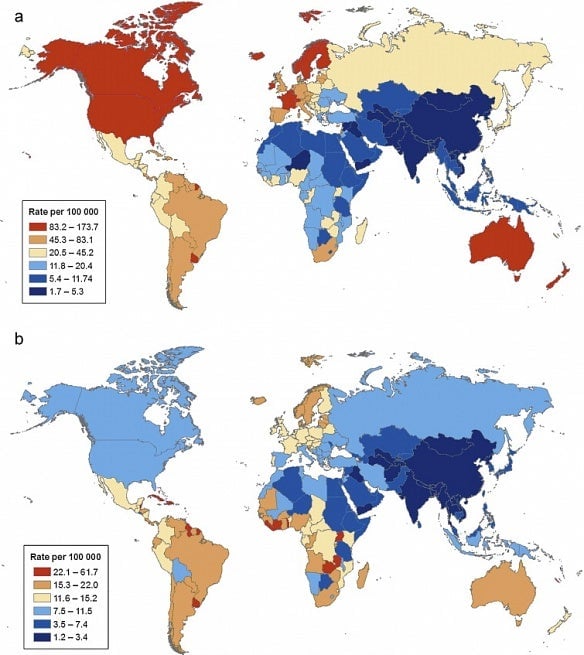

In 2012, 1.1 million men were diagnosed with prostate cancer worldwide. As the first map below shows, men in rich countries are a lot more likely to get prostate cancer (though South America has high rates too). However, as the second map shows, the risks of dying from it aren’t similarly spread.

To me, the top map implied that there was a link between the Western lifestyle and prostate cancer. Alas, cancer is never simple. Many things have been linked to it—not just high-fat diets and sedentary lifestyles, but plastics, Agent Orange, too much dairy, too little sunshine, and even being too tall. However, no absolute links for these risks have been made.

I fidgeted in my chair and stared holes into the posters behind my doctor’s head. He started asking me some questions about my pee. Urine is the bellwether for prostate cancer: The small gland hugs the urethra, through which both urine and ejaculate pass, so, when bad things happen to the prostate, it passes them along downstream. Was I having trouble urinating? Did it ever hurt? Was there ever blood in it? Had I been waking up in the middle of the night with bathroom urges? I felt us getting closer to the final check-up.

A rogue’s gallery of prostate cancer treatments

“There are many ways to treat prostate cancer,” Dr. Ashutosh Tewari, head of urologic oncology at New York’s Mt. Sinai Hospital, told me. “You can cut it, poison it, starve it, burn it, freeze it, or you can electrocute it.”

Cut it: Tewari’s specialty is laparoscopic surgery. This uses tiny robotic tools to surgically remove prostate tumors, usually through abdominal incisions (though perineal and rectal approaches are not unheard-of.) In expert hands, like Tewari’s, the dangers are low. However, the urethra runs through the prostate, and it is surrounded by a cluster of nerves that control erections. So there’s a risk of getting urinary incontinence and impotence.

Poison it: Chemotherapy is used in the worst cases, when the cancer has spread to other organs. Side-effects include hair loss, mouth sores, fatigue, nausea, forgetfulness, blood clots, bruising, allergies, numbness, and with one drug, a small risk of developing leukemia later in life. Personal experience watching family members deal with chemotherapy has left me dubious as to whether it’s better than just having the cancer.

Starve it: Prostate tumors feed on testosterone. Using either hormone therapy or surgical castration, your doctor can deprive your tumor of its food. This is not a cure, though, but a way to keep the tumor from growing. Side effects may include impotence, lowered libido, growing breasts, and, big surprise, depression.

Burn it: Thermal enhanced metastatic therapy (TEMT) uses magnetically-heated iron filaments to agitate cancer cells, making them more vulnerable to hormone therapy or chemotherapy. The burning is highly localized, and shouldn’t really affect other tissue, but they’re still testing this one out. Also still in clinical trials is High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU), which uses sound waves to heat and destroy cancer cells.

Freeze it: Cryotherapy is similar to brachytherapy in that it involves putting needles through your perineum. After numbing you or putting you to sleep, the doctor inserts six needles and sends in freezing chemicals. These create ice balls around the cancerous cells, killing them. Like brachytherapy, this one also requires a rectal ultrasound probe for guidance, but also comes with a catheter that circulates warm fluid into your urethra to keep it from freezing. Recovery is quick, except you might have to pee through a catheter for up to three weeks.

Electrocute it: For irreversible electroporation (IRE), six small wires are inserted through—you guessed it—needles in the perineum. These generate charges through cancerous cells, destroying their membranes and killing them (that’s the “irreversible” bit.) This frighteningly-named therapy is still in clinical trials, and not yet approved.

Irradiate it: Brachytherapy is a subspecies of radiation treatments. Doctors can also hit an early-stage tumor with external beam radiation. Since the prostate is hidden behind layers of other types of tissue, there’s a chance of collateral damage. The biggest danger is that the radiation will degrade the tissue in your intestines and rectum. The effect of this is—there’s no nice way to say it—to make it hard for you to keep your poop in.

Is there anything I can do?

The odds of getting prostate cancer are set; diet, exercise, and other lifestyle choices all make a negligible difference. One drug, finasteride, was shown to reduce prevalence by 25% in clinical trials. “But, if the men did get prostate cancer, they were more likely to have a higher grade [i.e. more aggressive] of it,” says Elizabeth Platz, a prostate cancer researcher from Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, Maryland. That catch-22 has held the drug back from FDA approval.

However, while diet, exercise, and so on may not much change your chances of getting the disease, they can have a huge effect on how terrible your experience with it will be. “The frequency of prostate cancer in overweight, unhealthy men is equal to that diagnosed in people without a sedentary lifestyle. However, obese men have more aggressive cases,” says Dr. Christopher Logothetis, chair and professor of Genitourinary Medical Oncology at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Aggressive cancers spread faster and further, which means more invasive treatments, slower recoveries, and greater chances of recurrence.

Do I have it?

My doctor asked me about my family history. Yes, my mother had breast cancer, so I should be aware but not alarmed. I’m white. I’m young. ”We don’t see prostate cancer in people who are 33 years old,” he told me. He almost seemed apologetic. There would be no digital rectal exam today.

Now I was disappointed. I told him that I was still nervous about my odds. This, he pointed out, was a good thing. “You’re paranoid, which means you’ll probably catch it early if you do eventually get cancer.” But he also warned me that there are no good ways to screen for cancer, and to be wary of results from a PSA test.

PSA tests measure how active your prostate is by measuring how much of the gland’s signature enzyme is present in your blood. Normal PSA levels are around one to 4.5 nanograms per milliliter of blood. In addition to checking the base levels, doctors look at how much PSA levels rise between check-ups. An increase of 0.75 ng/ml indicates that something might be wrong. But a high PSA score could mean nothing at all. Older men typically have higher scores, and a harmless case of swelling might be causing your prostate to churn out more of the enzyme. Or certain medications could artificially raise (or lower) your PSA levels. Or maybe you’re just riding your bike too much.

In fact, in 2011 a US government health task force ruled that PSA tests do more harm than good. ”Fear of underestimation results in overtreatment for those who don’t need it,” says Tewari, the laparoscopy expert from Mt. Sinai in New York, who has made it his mission to stop over-diagnosis.

At the very least, he told me, it can lead to unnecessary biopsies (when a tissue sample from the prostate is taken by inserting a needle through the urethra, perineum, or rectal wall.) In the worst cases, men have been getting aggressive treatments for relatively non-aggressive tumors. “This can lead to issues with urine control, with sexual function, with secondary cancers that can happen because of radiation,” says Tewari.

Tewari also made note of my paranoia. ”You might have too fearful of an approach to prostate cancer. You mentioned medieval more than once when we were discussing the various treatments. I don’t think it’s that medieval anymore.”

I agree, maybe I am fearful. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing. Fear is a great motivator, especially for those of us who are tired of hearing the same advice for every new ailment: Eat right, exercise, don’t smoke. Keeping those treatments in my mind helps me keep those habits in my life. Sometimes thinking about perineal needles is the only way I can stave off the craving for a pork chop, or get me off my ass on a day when I don’t want to be active. If I am destined for one (or several) of the methods in the prostate treatment palette, I’d rather get it over with quickly, and I think all of you men should want the same thing.