A US-Europe rare earths partnership is sandwiched by China

Last week, two North American companies announced a partnership to establish a US-Europe rare earths supply chain, part of a broader push to reduce reliance on China for the critical minerals.

Last week, two North American companies announced a partnership to establish a US-Europe rare earths supply chain, part of a broader push to reduce reliance on China for the critical minerals.

But though the firms’ efforts will help diversify rare earth supplies, a closer look at their business operations reveals deep ties with China that show how complicated it is to further Washington’s goal of building more secure and independent rare earth supply chains.

The joint initiative will see a rare earth supply chain spanning from the desert plateaus of Utah, US, to the small coastal town of Sillamäe in Estonia—an example of the kind of international collaboration that industry experts have advocated in order to secure the global rare earth supply chain.

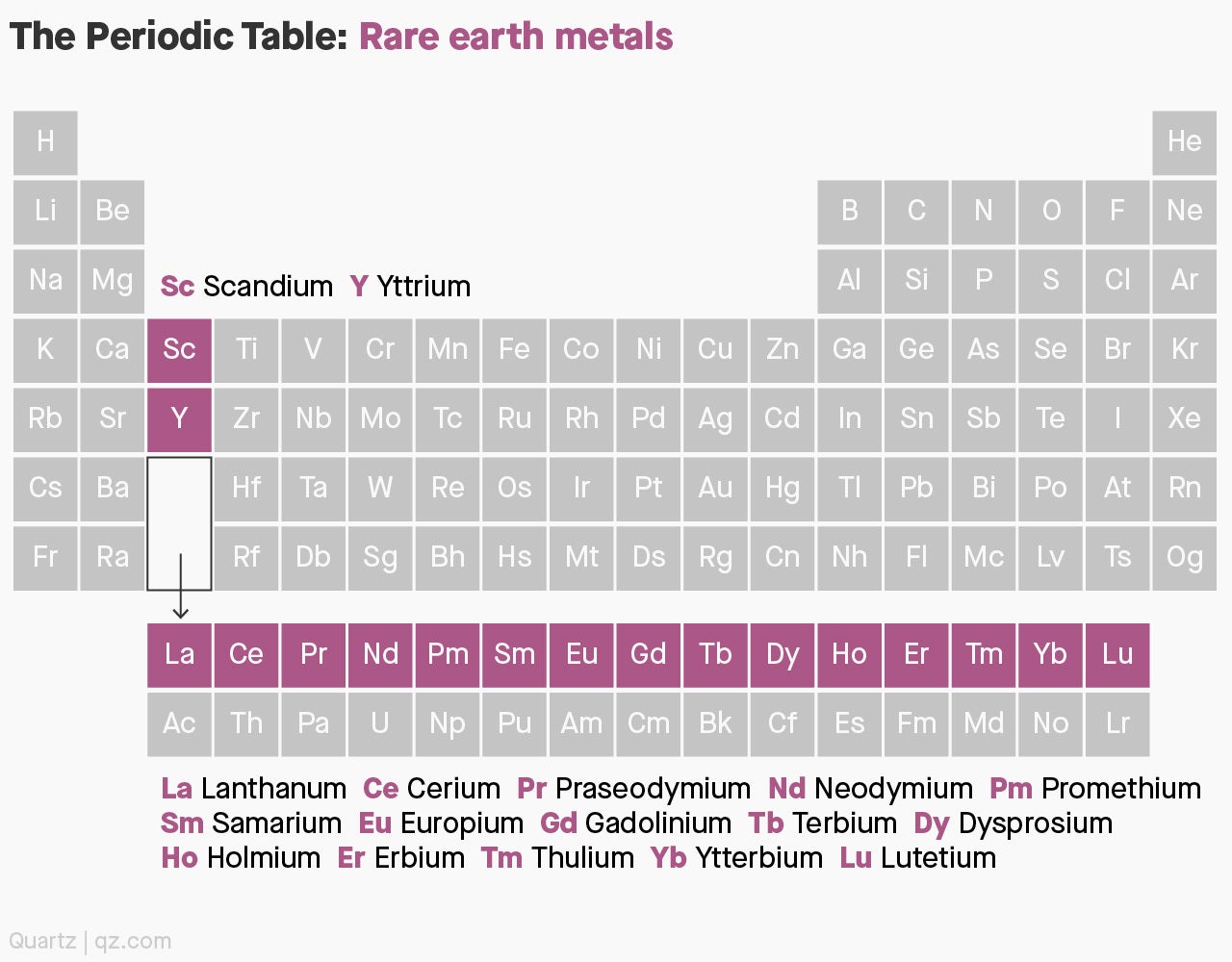

Rare earths are a group of 17 metals that are critical for the production of many electronic products that power the global economy, including military systems, electric vehicles, aircraft engines, and wind turbines. For now, China dominates the global production of these critical materials.

Here’s how the latest US-Europe chain works. The New York-listed Energy Fuels, a major American uranium miner, will process radioactive monazite sands to produce rare earth carbonates. It will then send those rare earth carbonates to Estonia, where the Canada-headquartered Neo Materials has a processing facility to separate the rare earths into individual elements for use in manufacturing high-tech products. The monazite sands, from which Energy Fuels extracts valuable uranium but also recovers rare earths, are supplied by US-based chemicals company Chemours.

“It’s our goal to play a significant role [in the US rare earth supply chain], and it’s mainly because the facility we have is significant,” said Mark Chalmers, president and CEO of Energy Fuels.

While current terms of the agreement represent what Chalmers estimates to be 7% to 9% of current US rare earth demand, the goal is to increase the amount of monazite processed at the firm’s Utah facility by “manifold, maybe tenfold, maybe greater” so as to satisfy a significant portion of domestic rare earth needs. Energy Fuels hopes to be able to develop its own rare earth separation capabilities at its Utah plant by 2024.

But in a reminder of how challenging it will be to build a rare earth supply chain that’s independent of China, both Chemours and Neo Materials—two companies bookending the upstream and downstream segments of the new US-Europe chain—have significant exposures to China.

🎧 For more intel on the global supply chain, listen to the Quartz Obsession podcast episode on rare earths. Or subscribe via: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Google | Stitcher.

Neo Materials is the only non-Chinese company in China licensed to process rare earths, according to the investment company Raymond James. Much of the company’s production capacity is also based in China. For example, two of its three critical minerals processing facilities are based in China. But the third facility, in Estonia, is much smaller, and the two Chinese facilities account for almost 80% of total processing capacity, according to the company (pdf). Moreover, 60% of its workforce of 1,850 full-time employees are based in China, according to latest company figures.

Chemours, the firm providing monazite sands to Energy Fuels, similarly has a significance presence in China. The firm has three production facilities in China, including two that are joint ventures with Chinese companies.

These foreign companies’ presence in China, which no doubt offers business opportunities for the firms, also helps China to advance its rare earths capabilities. “[T]he success of the Chinese downstream firms also depends on the development of the non-Chinese opponents in the industry,” said Yuzhou Shen, a doctoral candidate at the Colorado School of Mines. The downstream segment deals with the processing and high-tech application of rare earths, while the upstream segment deals with mining the ores.

The rare earths industry may be so globally integrated that it’s difficult for any one country to be totally self-sufficient. But if the goal is to be more insulated from Beijing, which has not ruled out weaponizing rare earths as a trade weapon, the difficulty of finding suppliers without deep business ties to China seems a cause for concern.

“It’s doable, but it’s hard” to build a rare earths supply chain completely independent of China, said Dane Chamorro, a partner at risk consultancy Control Risks. Even if a company has no business ties based in China, he said, if China represents a significant market then the firm is just as susceptible to pressure.

As senior director for international economics and competitiveness at the US National Security Council Peter Harrell put it last month in announcing president Joe Biden’s executive order to review the nation’s critical supply chains, “Our supply chain should not be vulnerable to manipulation by competitor nations.”

Chalmers, the Energy Fuels CEO, acknowledged Chemours’ and Neo Materials’ ties to China, and noted that goal of the US-Europe rare earth supply chain is to “complement Chinese capabilities,” rather than achieve decoupling.

“I don’t think it’s a case of completely disconnecting from China here. I think it’s a case of trying to be less dependent on China,” he said. “It’s a global economy…it’s not our intention to demonstrate that we’re completely disconnected from China.”