The geopolitical buzzword of the moment is the Indo-Pacific

Name a region that most people probably can’t identify on a map, but that European leaders think is the center of gravity of the world.

Name a region that most people probably can’t identify on a map, but that European leaders think is the center of gravity of the world.

I’ll wait.

The Indo-Pacific, you said? Shame on you for cheating.

The Indo-Pacific is a new geographic construction that means something different depending on who you’re talking to. Broadly speaking, according to the British think tank Policy Exchange (pdf, p. 15), it “stretches from the Indian sub-continent, up through southeast Asia to China and the northeast Asian countries of Japan and the Koreas,” and borders the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

You’ll have noticed that doesn’t encompass the UK or the EU—and yet both are formulating policies that will see them ‘pivot’ towards the region in the coming years, as they adjust their relationships with China and seek new opportunities for trade with the world’s richest emerging markets.

What is the Indo-Pacific?

The Indo-Pacific region is more of a political construct than a geographic one.

In its most expansive definition, it encompasses not just “inner” Indo-Pacific nations like Japan or India, but also “littoral” ones like Canada or Chile. It’s a rich and diverse place that contains, according to the US Indo-Pacific Command, “more than 50% of the world’s population, 3,000 different languages, several of the world’s largest militaries…two of the three largest economies…the most populous nation in the world, the largest democracy, and the largest Muslim-majority nation.”

It’s also the heart of global trade, “a region through which the world’s most critical sea lanes pass, in the Malacca Strait linking the Indian Ocean with the south China sea,” according to Policy Exchange.

What does it mean to pivot to the Indo-Pacific?

Whichever way you slice it up, the Indo-Pacific is an important part of the world—and European powers want a piece of the action.

When the UK released an Integrated Review of its foreign policy this week, the region was mentioned 32 times throughout the 114-page document, and was presented as the future of post-Brexit Britain‘s trade and foreign policy.

A few days before that, the EU’s top diplomat, Joseph Borrell, called on the EU to “set out, in the coming months, a common vision for its future Indo-Pacific engagement.” Several EU member states have already done so in the past few years, most prominently Germany last September (pdf).

By 2030, the UK plans to “be the European partner with the broadest and most integrated presence in the Indo-Pacific.” That involves applying to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Transpacific Partnership, which governs trade between 11 Pacific nations; becoming an official partner of the Association of southeast Asian Nations; and promoting British values, in part through the Indo-Pacific powers that are former British colonies and members of the Commonwealth of Nations.

Meanwhile, the EU plans to deepen its relationship with Japan and hold a summit in May with Indian prime minister Narendra Modi to launch a partnership with India on connectivity.

In spite of these grand plans, it’s not clear whether a pivot to the Indo-Pacific is a substantive foreign policy concept or just a buzzword. What is clear is that the British public has little understanding of the region and is not sold on the value of a pivot. According to a survey conducted recently by the British Foreign Policy Group (pdf, p. 52), 15% of Britons believe that the UK “should not focus on the Indo-Pacific as our security and economic interests lie elsewhere,” 37% don’t have an opinion about it, and “just 8% think the UK should make the Indo-Pacific the center of its foreign policy.”

This, says Chris Brannigan, a senior fellow at Policy Exchange, shows that the government hasn’t done a good enough job of “making the case domestically” for the pivot. He also argues that the next decade will make it clear to Brits that the Indo-Pacific is more central to their lives than they realize, and that “we can’t achieve the sort of change that affects people in this country without engaging in that particular region.”

The UK and EU approaches to the Indo-Pacific: More of the same?

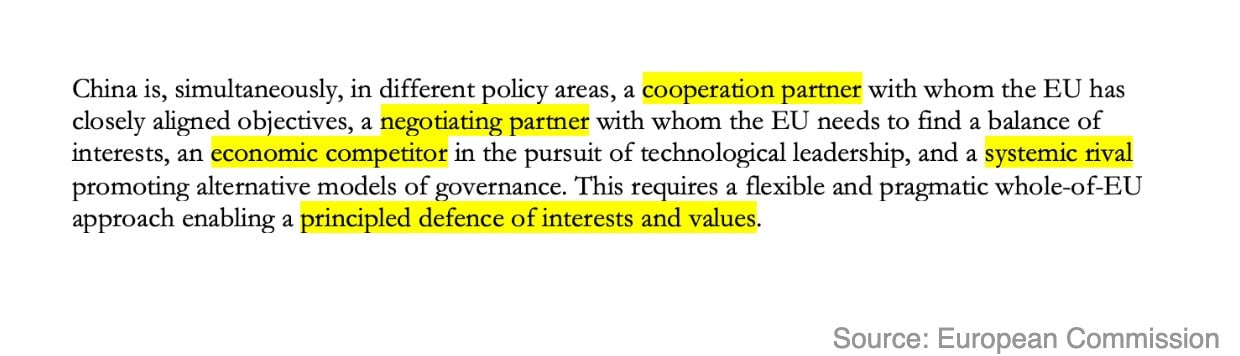

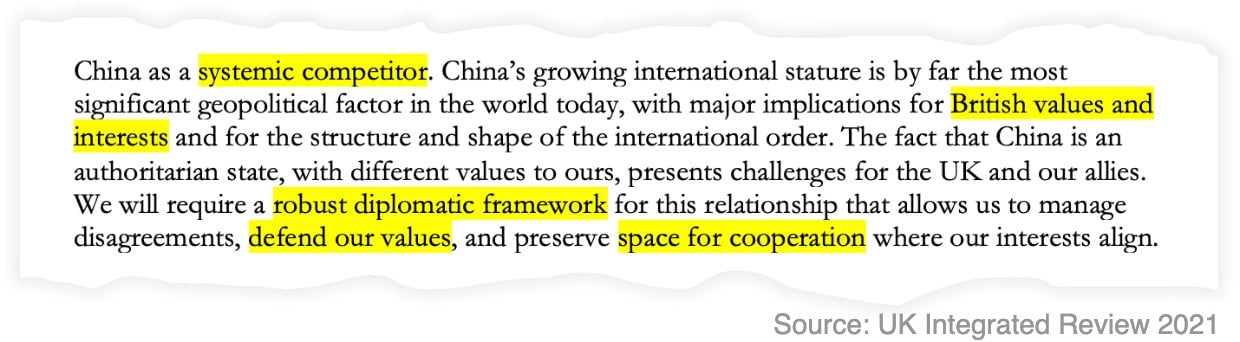

The UK and the EU strategies for the Indo-Pacific have a lot in common. They both identify India and Japan as key players and see security and climate change as likely areas of cooperation. Both view China simultaneously as a threat and an opportunity—in fact, in an almost comical fashion, the Integrated Review (pdf, p. 26) names Beijing a “systemic competitor” while the EU called it a “systemic rival” in 2019.

And yet both also want to deepen trade relations with China—the EU, through a Comprehensive Agreement on Investment it signed with Beijing late last year, and the UK through a commitment to “pursue a positive economic relationship.”

One of the motivations behind the Brexit referendum was that the UK, free of the constraints of a bureaucratic behemoth like the EU, would be free to shape its own distinct and more nimble foreign policy. And yet on the Indo-Pacific, London appears to trail behind Brussels, only to arrive at the same place.

It’s a contradiction that Tom Tugendhat, chair of the House of Commons’ foreign affairs committee and co-founder of the China Research Group of MPs, readily acknowledges. “There’s a lot in [the Integrated Review] that we could of course have done as part of the EU. Legally we could’ve done a lot of it; politically, would we have done? Possibly not.”

Through this lens, the EU is all talk and no action, while a sovereign UK is not. But both France and Germany are sending navy ships to the south China sea this year on freedom-of-navigation missions, as the UK is doing with aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth. To this, Tugendhat says, “maybe the difference is more in tone than in substance.”