Where Covid-19 came from is as much a political question as a scientific one

A year ago, as cases and death rates skyrocketed worldwide and Western countries implemented their first Covid-19 lockdowns, the question of where the virus came from wasn’t top of mind for scientists. The short answer sufficed: SARS-CoV-2 seemed to come from China—specifically, the city of Wuhan, and probably at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in late 2019. There were early reports that it came from bats.

A year ago, as cases and death rates skyrocketed worldwide and Western countries implemented their first Covid-19 lockdowns, the question of where the virus came from wasn’t top of mind for scientists. The short answer sufficed: SARS-CoV-2 seemed to come from China—specifically, the city of Wuhan, and probably at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in late 2019. There were early reports that it came from bats.

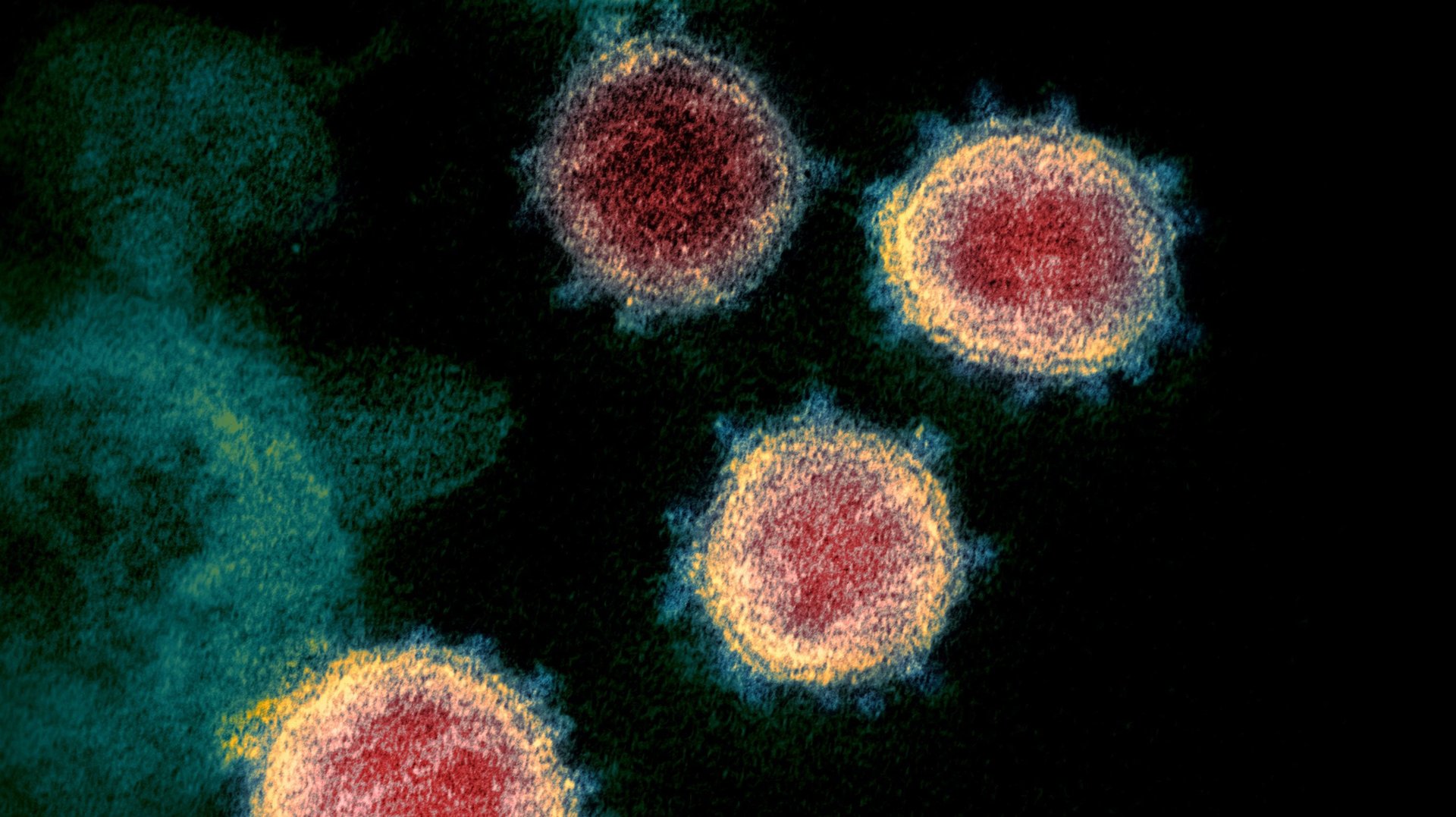

Yet since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 to be a pandemic, concrete origins of SARS-CoV-2 haven’t yet emerged. Though scientists are uncertain about its animal origins, they also haven’t been able to rule out the possibility that SARS-CoV-2 came from somewhere elsewhere—namely, that it’s an escaped specimen from a lab studying dangerous pathogens.

Finding the virus’ origin matters. “The more we can understand about how this [pandemic] happened, the better chance we have at stopping it from happening in the future,” says Rasmus Nielsen, a computational geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley.

But finding the virus’ origins is a live wire; it could have massive geopolitical consequences. A spillover from animals to humans would mean that the SARS-CoV-2 happened naturally, and that scientists would need to work with public health officials to develop adequate pandemic preparedness. These types of pathogens, which scientists call “zoonotic,” are fairly common in virology. Other zoonotic coronaviruses were behind the 2003 SARS pandemic and 2012 MERS outbreak, and there’s reason to think such a crossover will happen again.

A lab origin could mean that some individual or group may be to blame. Though it’s impossible for scientist-detectives to tie a single event to the deaths of nearly 3 million people (confounding factors, like inadequate public health responses, played a role too), a finding to that effect could result in an upheaval of the way scientists research potential pathogens in the future.

It could also damage China’s relationship with the rest of the world. Its government has been frustratingly opaque about information about the early days of the pandemic, and has failed to cooperate with global scientists’ efforts to get to an answer. “Chinese researchers have been told they are not allowed to publish results on the origin of the virus, and, at the same time, [virus] samples from China aren’t being shared,” says Nielsen.

Not knowing where the SARS-CoV-2 came from leaves the world vulnerable to future pandemics, but there are real geopolitical and scientific consequences to finding the definitive answer.

What we (don’t) know about SARS-CoV-2 origins

So far, scientists have some preliminary answers. They know that the original Covid-19 outbreak occurred in a Wuhan wet market. But they also know that it’s unlikely the virus came from there. So far, no animals nearby have been found with any kind of similar virus. Someone, maybe a traveler who picked it up elsewhere, may have brought it there instead.

But that’s where the definitive knowledge runs out. The WHO sent 10 researchers to investigate Covid-19’s origins; they’re expected to release a full report in the coming days. But the global research community also knows that the Chinese government is heavily involved in the final public outcome of this report, as it has been in previous pandemic investigations.

Past pandemics have paved the way for the zoonotic hypothesis. “Prior to SARS-CoV-2, there were five viral pandemics since 1900 for which we have molecular evidence (the influenza pandemics of 1918, 1957, 1968, 1977, and 2009). Four of these five respiratory pandemics were due to viruses jumping directly from animals to humans,” Jesse Bloom, a computational biologist who studies viruses at the Fred Hutch Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, told Quartz in an email. Only one—a flu pandemic in 1977—likely came from a vaccine trial gone awry. From a statistical standpoint, it makes sense that this pandemic also has animal origins—we just may not have found them yet.

Even though there’s early consensus around the zoonotic hypothesis, virologists can’t yet be sure. “The truth is, we don’t really have the evidence now,” to identify the SARs-CoV-2 origin story one way or another, says Nielsen. He believes that anyone who dismisses one hypothesis over another at this point isn’t considering all the available data.

For one thing, scientists haven’t found a genetic trail leading directly to SARS-CoV-2. “The closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 is a virus called RaTG13,” says Bloom. RaTG13 (named for Rhinolophus affinis, the horseshoe bat in whose droppings it was found) originated in 2013 in the Yunnan province in China. But that’s about 1200 km (800 miles) away from Wuhan—not close, in other words.

It’s also not genetically similar enough to be a direct predecessor of SARS-CoV-2, Bloom says. There must be an intermediate virus that connects RaTG13 and SARS-CoV-2. One possible virus may have been responsible for the pneumonia that killed three out of six infected miners in Mojian, a city in Yunnan, in 2013, but that virus was never genetically sequenced.

Viruses being studied for research are rarely the cause of pandemics. And yet, Wuhan is also home to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which has the highest possible biosafety rating and has studied coronaviruses, including RaTG13. But according to Undark Magazine, there have been instances of safety violations at this center in the past. In 2017, US state department officials flagged that the facility requested help finding and training technicians capable of meeting all the safety criteria required for work on coronaviruses. And virology labs, while crucial for the advancement of science and prevention of future pandemics, are inherently risky: Leaks led to an outbreak of SARS-CoV-1 in 2004 in China and smallpox in 1978 in the UK—two years after the WHO declared it to be the first (and only) eradicated virus. Thankfully, these outbreaks were quickly contained because of public health officials’ prompt responses to quarantine any possible contacts.

For all these tidbits of evidence scientists have, they still can’t put together a concrete theory about how SARS-CoV-2 came to be. In any area of research, scientists are reluctant to jump to conclusions. But when the international reputation of a global player like China is at stake, speculation can have even bigger consequences.

A dangerous blame game

Scientists’ genuine question about the virus’ origins was poorly timed. As Undark points out, it was the beginning of a presidential election in the US, where the incumbent leader spewed racist rhetoric throughout his tenure. From his primetime platforms, Trump referred to SARS-CoV-2 as the “China virus,” which directly led to a rise in anti-Asian hate speech online. Some US lawmakers have even linked this coronavirus xenophobia to the recent murders of eight women, six of whom were Asian, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Many researchers and lay people felt compelled to quickly distance themselves from any theory that could tie them to anti-Asian rhetoric. In Feb. 2020, a group of dozens of researchers published a letter in a prominent health journal stating that it was dangerous to support any Covid-19 origin hypothesis besides the zoonotic one. They referred to the idea that it came from a lab as a “conspiracy theory”—one that had the potential to impact innocent people from China as well as Asian people worldwide. After the Chinese government and Wuhan Institute of Virology vehemently denied that it originated at the bench in April 2020, Trump stated he was still confident about the lab leak theory. As a result, it was extremely difficult for researchers to seriously study whether SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab, says Alina Chan, a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University.

The WHO squashed the lab theory. In Feb. 2021, Peter Ben Embarek, a WHO food-safety scientist, said that a lab leak was “extremely unlikely.” However, the organization has since rolled that statement back as the delegation of scientists works on an evidence-based theory.

Consequences

The results of the researchers’ much-anticipated report still carry the potential for immense fallout. The goal is to understand the virus’ origins enough to be prepared for, or prevent, the next pandemic. If scientists conclude that the virus originated naturally, virologists would likely be to increase their focus on finding precursors to those next pandemic-causing viruses. Practically, this would involve “intensive analysis of the bat caves where we know that most closest relatives of [potentially zoonotic] viruses are,” says Nielsen. That kind of work is not new—that’s what teams at the Wuhan Institute of Virology and other labs are already doing, and presumably governments and scientific organizations would free up more funding for it.

If SARS-CoV-2 came from a lab, the result would likely be a global crackdown on all high-risk biosafety labs, says Chan. There would be a push to relocate any of these high-security biosafety labs to more remote locations where, if a virus escaped through an accident or breach in safety protocol, it would be easier to contain. That might stand in the way of these labs being able to attract the best researchers; as Chan points out, scientists are people, too, and those who have set up their homes in really nice cities don’t want to live in the middle of nowhere.

More security in labs wouldn’t be a bad thing, nor would increased surveillance in the wild. But the political blame game that comes with the SARS-CoV-2 origin story will likely taint the science around it for decades—and could potentially threaten our preparedness for the next pandemic.