The ECB has loaded its €1-trillion bazooka, but can’t decide whether to use it

The talk over the weekend was that the European Central Bank seems to be preparing a new round of stimulus to kickstart the euro zone’s sputtering economy. A troublesome combination of weak growth, falling inflation, and a strong currency is giving policymakers headaches.

The talk over the weekend was that the European Central Bank seems to be preparing a new round of stimulus to kickstart the euro zone’s sputtering economy. A troublesome combination of weak growth, falling inflation, and a strong currency is giving policymakers headaches.

To this end, the latest gauge of the euro zone’s health, a reading of industrial production (pdf), is frustratingly inconclusive. Factory output in February beat expectations, but January’s previously reported results were revised lower. Manufacturing across the bloc is now growing at 1.7% per year, a good-but-not-great pace. The latest data is neither strong enough for the ECB to shelve its plans for costly stimulus measures, nor weak enough to trigger them immediately.

Ever since former US treasury secretary Hank Paulson described America’s economic bailout strategy as akin to packing a financial “bazooka,” analysts have questioned whether Europe can muster similar firepower. The ECB has reportedly readied a plan to bombard the euro zone with some €1 trillion ($1.38 trillion) in newly created money, but nobody is sure whether it would ever be willing to put it into action.

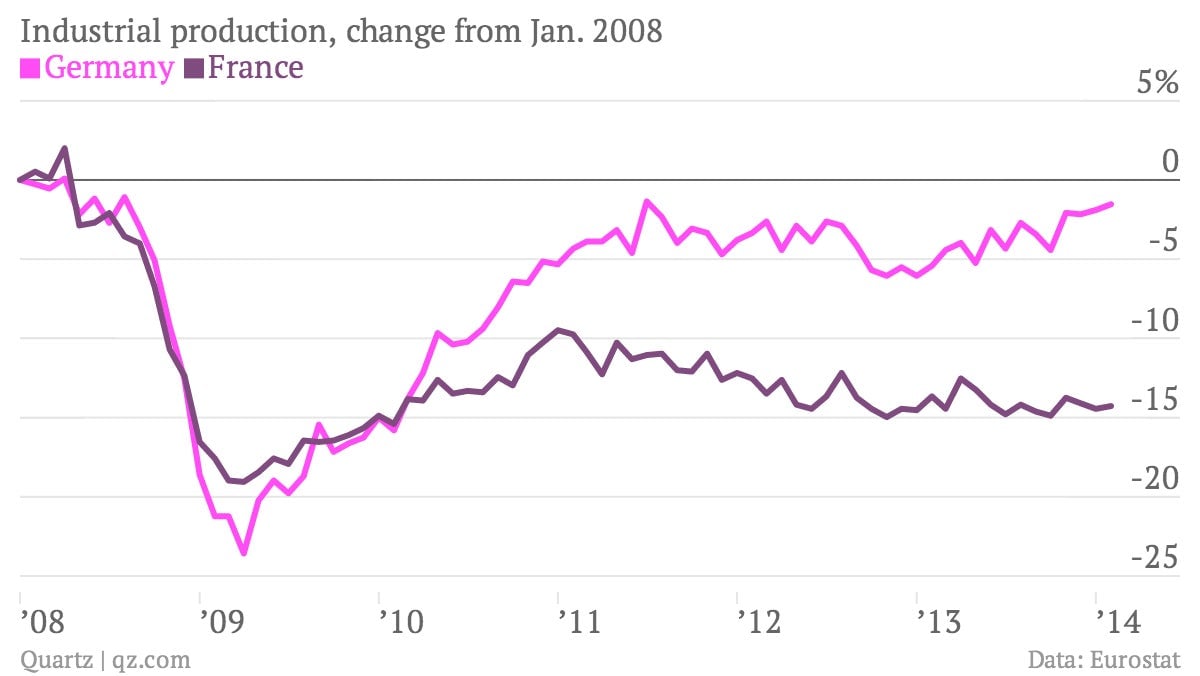

The latest manufacturing data shows how widely the health of euro zone members varies, a big source of the ECB’s indecision. The difference between the bloc’s two largest members, Germany and France, is particularly stark. Germany’s factories are almost as busy as they were before the financial crisis, while France’s have been stagnating:

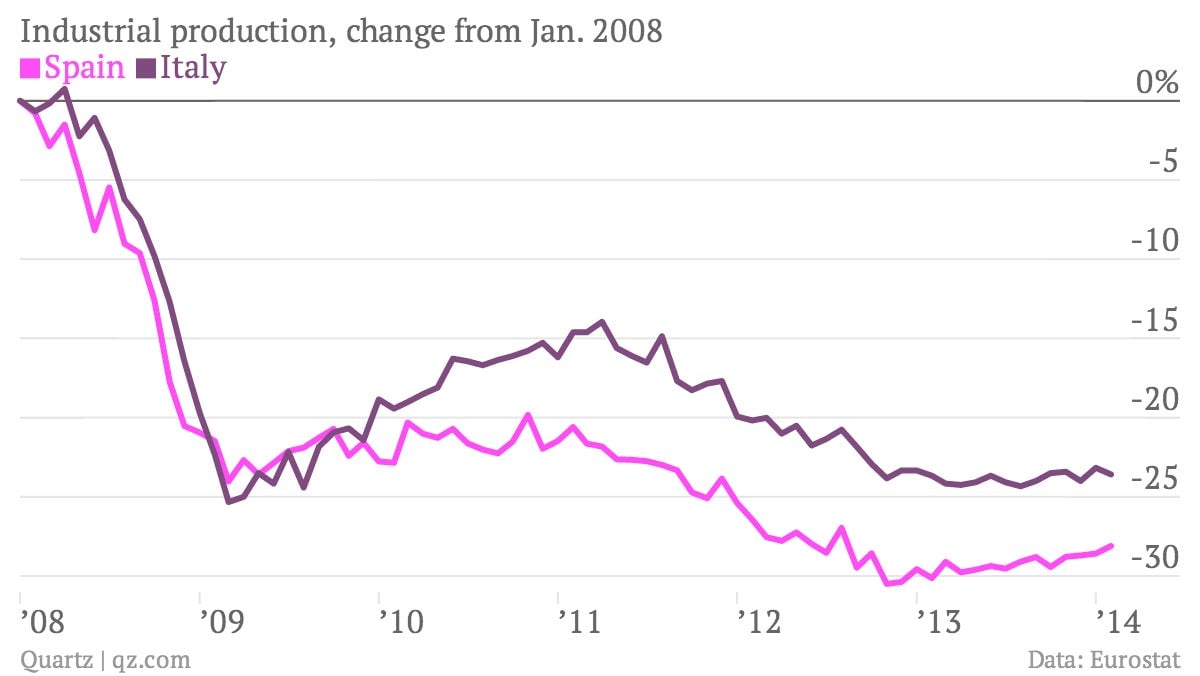

Conditions in Italy and Spain look like they have bottomed out, but the recent recovery—such as it is—isn’t much to get excited about:

It’s not all bad news, but the euro members showing the biggest gains are among the smallest nations—Estonia, for example. Slovakia, meanwhile, has been riding the recovery in the region’s car industry, which makes up a big part of its industrial base. Manufacturing activity in both of these countries is now almost 10% above pre-crisis levels, the strongest results among euro members:

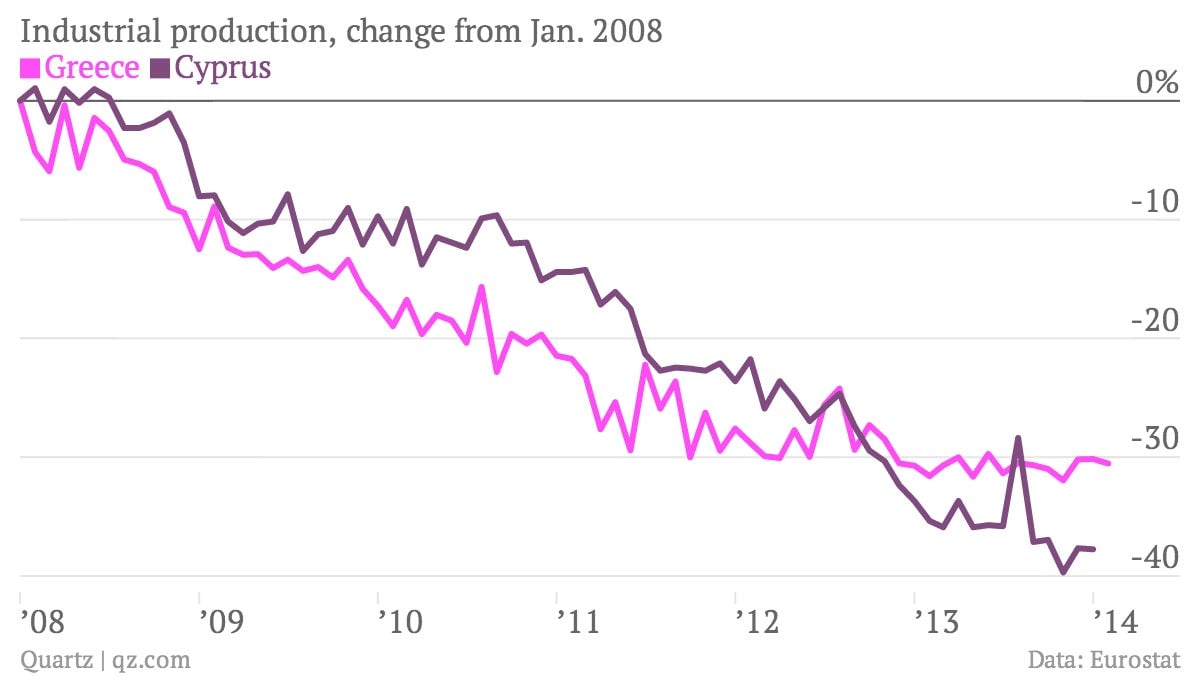

And then there are the basket cases. Factory output in Greece and Cyprus is as bad as it has ever been:

This makes the Greek bond-buying bonanza last week yet another confusing mixed message for the ECB to consider. Investors are snapping up the euro zone’s riskiest assets as if the worst of the crisis is over, which is good news in terms of lowering hard-hit governments’ borrowing costs, but may also encourage officials to lighten up on unpopular but necessary reforms. This could make the ECB’s job tougher (ie, more expensive) if it eventually decides to act more decisively to shore up the economy.

What to do? As ever in a union of 18 disparate countries, there is never one easy answer.