The carbon footprint of creating and selling an NFT artwork

In February, a gif of a cat with a Pop-Tart body sold for $600,000. On March 1, musical artist Grimes sold several videos for $6 million. And, on March 11, a single jpeg file sold for $69 million, becoming the third most expensive artwork sold by a living artist.

In February, a gif of a cat with a Pop-Tart body sold for $600,000. On March 1, musical artist Grimes sold several videos for $6 million. And, on March 11, a single jpeg file sold for $69 million, becoming the third most expensive artwork sold by a living artist.

Despite their substantial price tags, none of these works exist in the physical realm. They are purely digital, examples of what’s known as cryptoart or Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs).

NFTs have exploded in popularity recently, with sales increasing by 1700% between December 2020 and February 2021. Frothy press coverage touts the riches artists stand to gain. Basic statistics seem to bear this story out—even aside from these headline-garnering sales, the average NFT sells for about $975.

But behind this excitement lies another, quieter, story: NFTs have an enormous environmental impact, one that should give artists and customers pause before jumping in on the trend.

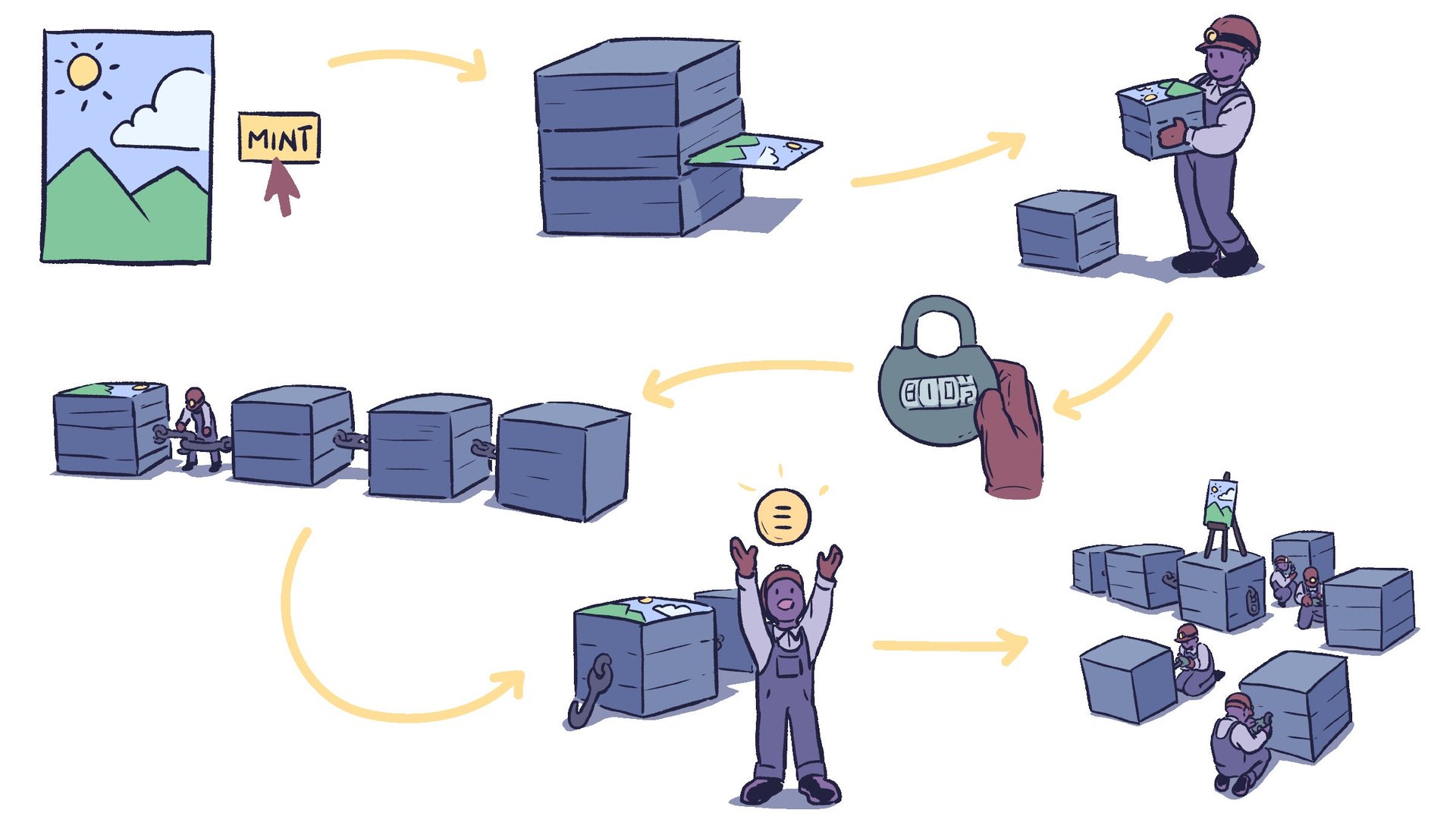

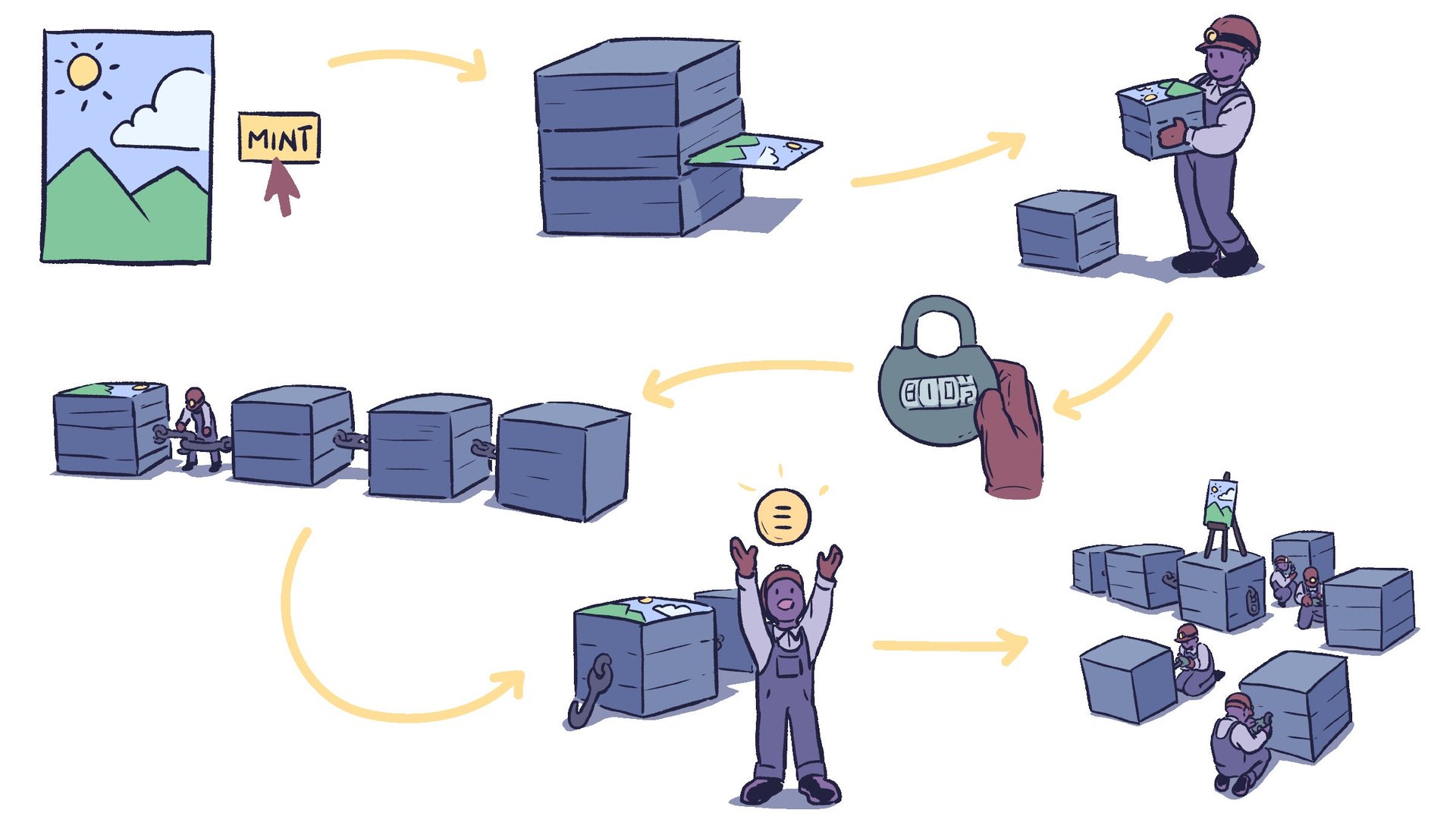

To understand the environmental impact, it’s necessary to understand exactly how this cryptoart is created and sold.

Imagine that an artist digitally creates and sells a piece of art. In scenario one, she prints out that art, packages it up, and ships it to her customer. In scenario two, she sells it as an NFT using an Ethereum-based service. Let’s walk through the carbon cost of each scenario, step by step.

The NFT art market is at an inflection point

Rarely are regular consumers in today’s world granted such a powerful environmental choice. Most people drive cars, eat meat, and wear mass-produced clothing because there are no easy alternatives; the systems that encourage these behaviors were put in place far before any of us were born.

Cryptoart, however, is not yet as embedded in our society. There is still time to prevent this from becoming the normal way to support artists.

There are several ways this could work.

The simplest would be not to participate in buying or selling cryptoart at all, and instead continue to support artists via traditional channels.

Another would be to choose better cryptoart platforms. The method described above is called Proof of Work. A miner must prove they have done computational work before they can add a block to a blockchain. Proof of Work was intentionally designed to be inefficient to make adding fraudulent transactions unprofitable for malicious actors, and it is the method behind most of the popular NFT-minting websites.

Proof of Work vs Proof of Stake crypto

Proof of Work is not the only option for handling crypto transactions. A leading alternative is known as Proof of Stake. In a Proof of Stake system, users are randomly awarded the ability to add new blocks based on how much cryptocurrency they own, not on how much computational work they can do. The more a user is invested in the currency, the more likely they will be the “winner” who is paid to add a new block to the chain.

Proponents tout Proof of Stake as being 99% more energy efficient than Proof of Work. That would bring down the carbon footprint of the average NFT to around 2.11 kg CO2, or about the same as mailing a physical piece of art cross-country.

Many Proof of Stake cryptoart platforms currently exist. They are smaller than their Proof of Work competitors, and have yet to generate the eye-popping sales figures seen in the news, but they offer a way to support NFT artists without absurd carbon emissions.