From Norwegian salmon to basketball, a brief history of China’s patriotic consumer boycotts

In China, the fate of a foreign company can change overnight.

In China, the fate of a foreign company can change overnight.

Brands including H&M, Nike, and Zara are learning this lesson the hard way, as they face consumer boycotts for comments they have made expressing concern over the use of forced labor in Xinjiang, or pledges not to use cotton from there. And despite their flip-flops, and efforts to tell one story to Western consumers and another to Chinese ones, the backlash is only growing.

Beijing is accused of having detained around 1 million Uyghurs and members of other ethnic minority groups in camps in the far western region, prompting sanctions of firms including apparel and tech suppliers by the US last year. The authorities have defended the camps as necessary for eradicating extremist indoctrination (the Uyghurs are largely Muslim). More recently Europe, the US and others last week sanctioned a number of Chinese officials in connection with alleged abuses in Xinjiang, and the boycotts began soon after.

Nationalistic consumer activism is an intensifying phenomenon in China—it’s now one of the few forms of public dissent that’s allowed.

As Beijing has become more comfortable flexing its muscles toward countries who present challenges to its policies, its citizens have also felt encouraged to express discontent with foreign companies. In past years, international brands have had to apologize time and again for “hurting the sentiments of the Chinese people,” whether by misrepresenting Taiwan as an independent country in an online drop-down menu or quoting figures like Tibetan spiritual leader the Dalai Lama, whom Beijing sees as a separatist figure. The boycotts have left various degrees of scars on companies, with some firms seemingly bouncing back quickly, while others have largely withdrawn from the market.

Here’s what happened in five of the most prominent consumer boycotts in China.

The NBA

A tweet showing support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests from Daryl Morey, the then general manager of the Houston Rockets, set off a storm in October 2019 around the National Basketball Association. Shortly after Morey tweeted and then deleted a picture that included words “Fight for freedom, stand with Hong Kong,” the Chinese Basketball Association, state broadcaster CCTV, and other partners said they would end cooperation with the Rockets. Rockets and league merchandise also appeared to have been removed from major e-commerce platforms including Taobao and Pinduoduo at the time.

Although many observers predicted that the boycott would push the league to choose between its more than $4 billion China business and upholding the right to freedom of speech, things instead de-escalated quickly. Beijing reportedly curbed nationalist sentiment for fear of the episode hurting its global image. A scheduled game went ahead with good attendance though related press events were canceled.

In October, state broadcaster CCTV announced that it had resumed the streaming of NBA games, which it had suspended in 2019 over Morey’s tweet, citing the “constant expression of goodwill” (link in Chinese) from the NBA towards the Chinese audience. NBA and Rockets merchandise is also available on Chinese e-commerce platforms, according to a search today by Quartz.

Dolce & Gabbana

In November 2018, the Italian fashion house’s promotional videos angered Chinese consumers who saw them as racist and sexist. The ads that sparked the controversy depicted a Chinese woman using chopsticks to eat food like pizza and cannoli clumsily, and awkwardly struggling at times. In one of the videos, the narrator asks the giggling actress in Chinese, “Is it too huge for you?”

D&G had to remove the videos from Chinese platforms. It also apologized for its co-founder Stefano Gabbana’s response regarding the backlash to an Instagram user, in which he used the phrase ” China ignorant dirty smelling mafia” in a direct message on the app [the company said Gabbana’s account was hacked]. The brand hasn’t really recovered from the boycott, as it has remained an example of foreign arrogance often cited by Chinese internet users. Its presence last year at a Chinese exhibition caused another backlash.

Norwegian salmon

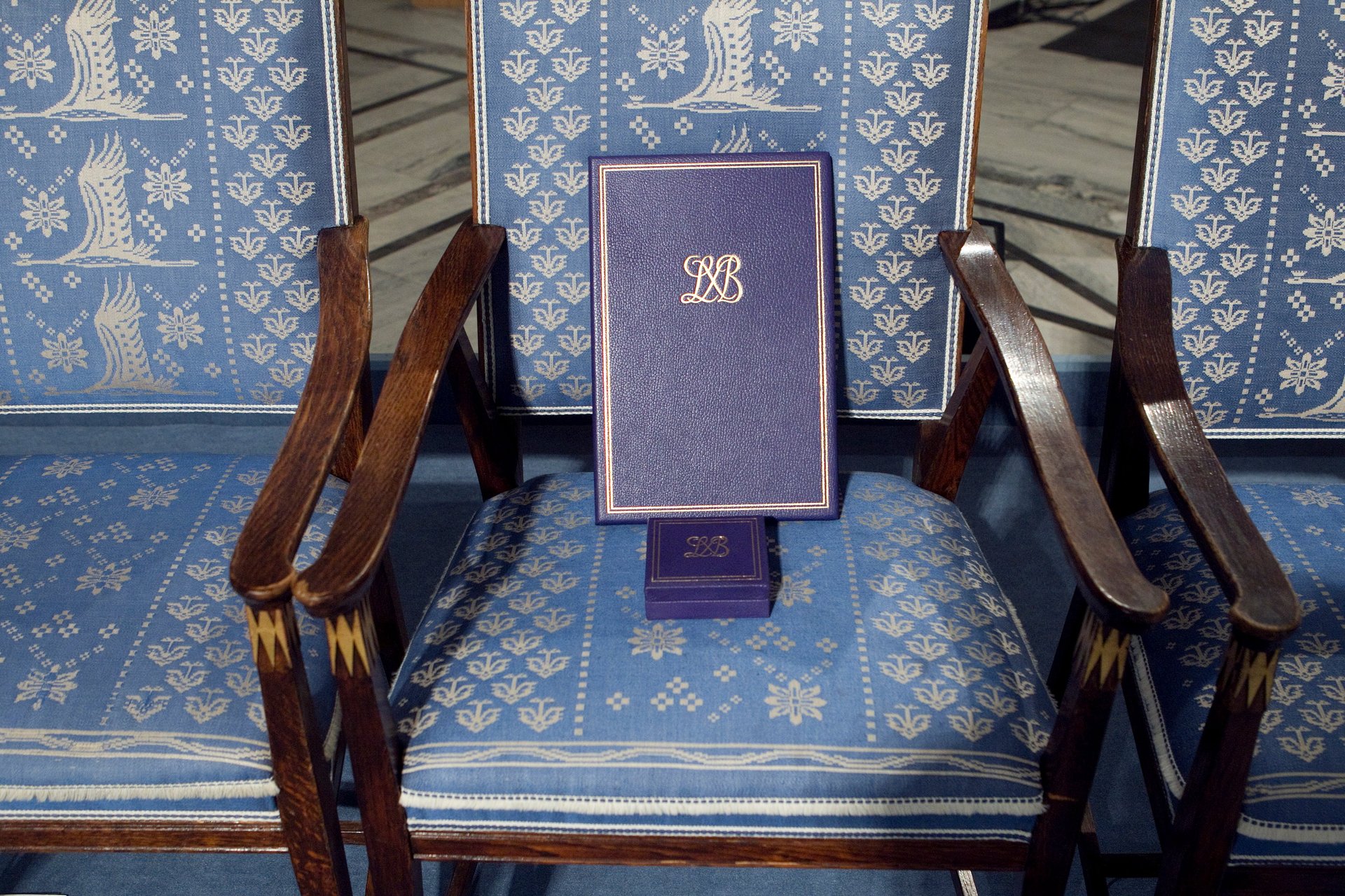

Norway, the world’s biggest producer of salmon, drew the ire of Beijing after it gave the Nobel peace prize to Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo in 2010—at a ceremony in Oslo the award was famously placed on an empty chair as Liu was then imprisoned in China. He later died in custody in 2017.

China’s imports of salmon from Norway plummeted until 2016, when the two countries resumed their diplomatic ties after the row over Liu. Last July, after some Chinese buyers’ suspended imports of foreign salmon citing fear of its potential to carry the Covid-19 virus, Beijing resumed imports of the product from countries including Norway as authorities concluded it was safe to eat.

Lotte Group

Perhaps no one knows the world of pain that can be inflicted by a Chinese boycott as well as South Korea.

In 2017, it saw tourism, video games, and a major conglomerate targeted after the country decided move ahead with plans with the US to build the anti-missile system Thaad, which was opposed by Beijing.

The South Korean retailer Lotte, whose land swap deal provided a site for the system, was particularly hard hit. It was ordered by authorities to close a large number of outlets of its supermarket chain, after Chinese consumers initiated a boycott of the company. In 2019, the company said it would sell its food production facilities in China, following its supermarket chain Lotte Mart’s earlier decision to make a full exit from the country.

In December, China approved the first South Korean video game in four years raising hopes of a thaw. Post-pandemic tourist arrivals to South Korea will show just how much of warming there will be.

Japanese cars

Many Japanese carmakers, including Toyota and Nissan, routinely see their joint ventures with Chinese entities among the top 10 spots (link in Chinese) in the country’s auto industry in terms of sales.

But in 2012, as tensions between China and Japan were running high over their disputed Senkaku Islands [called Diaoyu islands in China] in the east China Sea, anti-Japan protests swept across a dozen Chinese cities. Many protesters called for a boycott of Japanese brands ranging from cars from Toyota to electronic goods from Sony.

The outrage against Japanese goods led to one of the ugliest episodes ever in the history of China’s consumer boycotts: a man in the city of Xi’an who was driving a Toyota had his skull smashed by a protester with a bicycle lock. The attacker was sentenced to 10 years in jail, while the injured man was left with lasting disabilities (link in Chinese). Internet users coined the term “U-shaped lock,” a reference to the weapon used to attack the car owner, as a metaphor to describe excessive nationalist sentiment.