This is how we make sure we never lose a plane again

Malaysia Air flight 370’s disappearance is more disturbing to the public than previous airline disasters because the all-pervasive smartphone has created a consumer expectation for accurate location. If a consumer can instantly know his or her exact location and that of family members, friends and even pets on a smartphone map, why is the location of Malaysia Air 370 still a mystery?

Malaysia Air flight 370’s disappearance is more disturbing to the public than previous airline disasters because the all-pervasive smartphone has created a consumer expectation for accurate location. If a consumer can instantly know his or her exact location and that of family members, friends and even pets on a smartphone map, why is the location of Malaysia Air 370 still a mystery?

Consumers are correct to wonder–there is, in fact, a technical solution that would make it much less likely that we would lose track of airplanes. In light of this disaster, systems that stream cockpit voice conversations and flight data to the ground have emerged into public view as an alternative to today’s blackboxes. This solution matches the consumers’ expectation to instantly know location.

This would be an entirely new system with a long lead time to go from concept to installation on the world’s airline fleets. The lead time would be even longer because it is not currently in deliberation by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), an agency of the United Nations that governs civil aviation. If commercial aircraft were outfitted with flight data and voice recorders like some US military planes have been for more than a decade, flight 370 would no longer be a mystery.

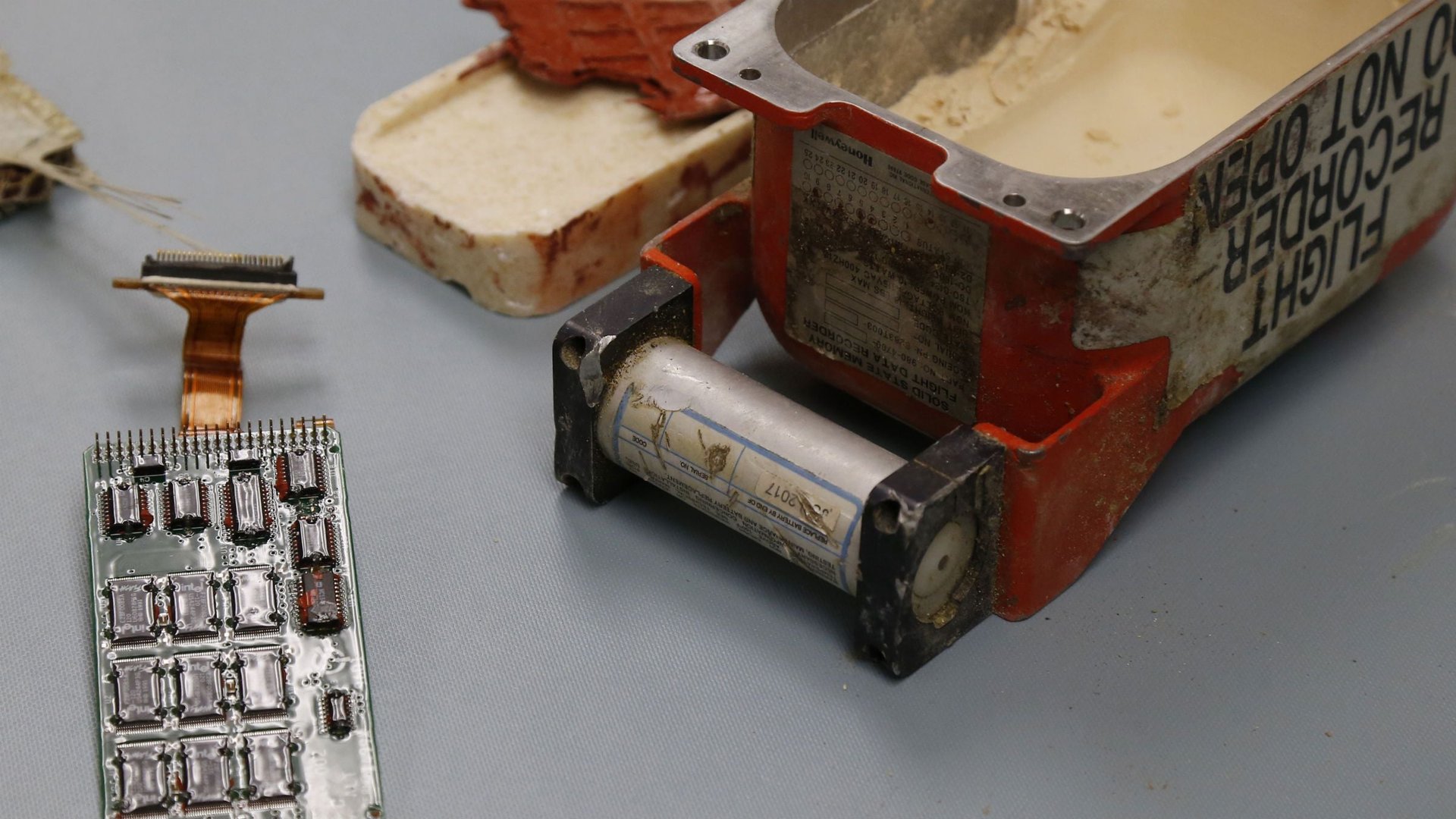

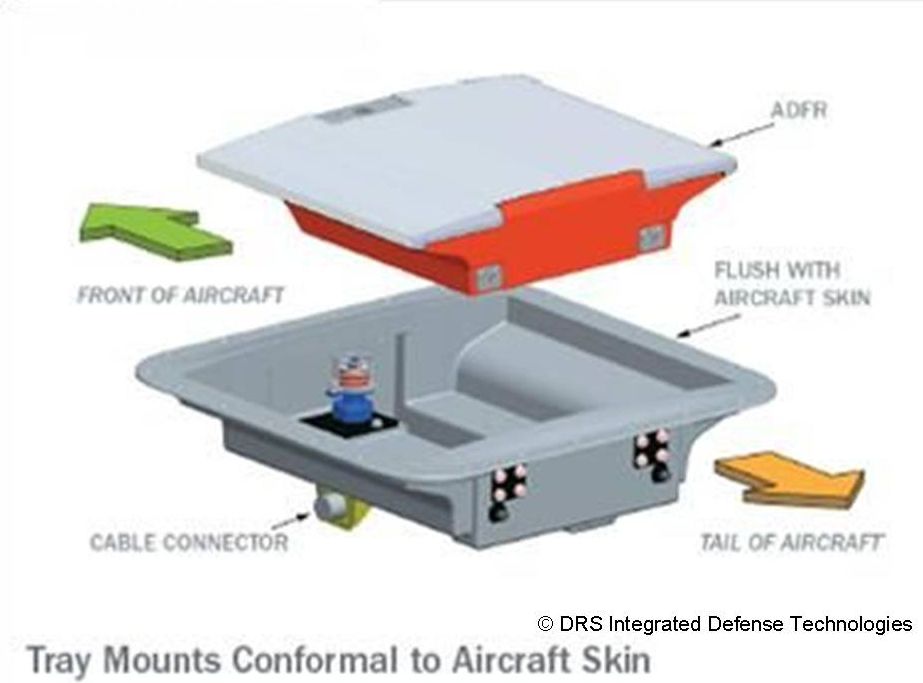

The military version of blackboxes called Automatic Deployable Flight Recorders (ADFR) do the same job as those used in civil aircraft with one major difference: on impact the ADFR separates from the aircraft. Mounted flush into the skin of the aircraft’s tail, the ADFR is an airfoil. Upon release, it enters the aircraft’s slipstream, flying it away from the crash. It its buoyant, so should it land in water, it will float. Upon separation from the aircraft the ADFR initiates an Emergency Locator Transmitter ELT sending a satellite signal with the aircraft’s country of registration, the tail number and the location where the ADFR was released. Using the ELT signal, search and rescue teams can locate and retrieve the flight recorders. Rightfully so, authorities have focused public attention on bringing closure to the families of the victims.

But behind the scenes the aircraft manufacturers, airlines and transportation regulators around the world should be focused on what happened in order to protect the safety of the 3.3 billion passengers forecasted by the International Air Transport Association IATA to fly in 2014. But they can’t; not until the flight data and voice recorders are recovered, if ever.

The 2009 Air France flight 447 disaster emphasizes the importance of acquiring the blackbox data quickly. For nearly two years the flight recorders were held in Davey Jones’ locker, 13,000 feet below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean until a team from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute using sophisticated equipment located and recovered them.

It took another month for a preliminary report to surface about how the passengers and crew of flight 447 met their fate and another year for a final report to be released citing pilot error due to instrument malfunction. The recommendations to prevent another such disaster were the replacement of the air speed indicators and pilot training. Meanwhile, based on IATA estimates about 6 billion passengers flew between the date of the Air France flight 447 disaster and the preliminary report.

Not all of course flew on the affected aircraft, the Airbus 330, but no one knows how many aircraft were at risk of pilot error due to inaccurate or inoperable air speed indicators. In response to Air France Flight 447, the ICAO convened a working group comprised of 120 of its members including state investigation authorities, regulators and aircraft manufacturers that is deliberating ADFRs and other measures to reduce the predicted radius of a water crash to six nautical miles.

The glacially slow innovation cycle of aircraft safety in this case is presumably due to the necessity to reach consensus within the large international ICAO membership representing the public and private sectors of the air transportation industry. Flight recorders carry a treasure trove of information. Two hours of the pilot and copilot’s conversations, the pilots and aircraft controllers’ conversations, and the ambient cockpit sounds are all continuously recorded. The ICAO recommends that about one hundred flight parameters are recorded like GPS, altitude, positions of the flaps and rudder and engine data. But aircraft manufacturers have added as many as a thousand parameters on newer evermore digital large aircraft, so investigators have a rich source from which to piece together the cause of a crash.

Did terrorists or a rogue pilot take control? What caused the flight’s communications systems to suddenly stop transmitting? Was the disaster caused by pilot error or equipment failure or both? If Malaysia Air flight 370 had an ADFR these questions would be answered. And the answer to most the pressing safety questions would now be in development by accident investigators: do aircraft manufacturers’ urgently need to make repairs to aircraft or do airline pilots urgently need to be trained?

The cost of adding ADFRs to new aircraft and retrofitting aircraft now in service is not available at the time of publication. Since aircraft manufacturers build both military and civilian aircraft, costs for civilian versions of the ADFR’s should be easily derived. Compared to mustering air forces and navies and contracting with under sea recovery experts, the economics of ADFRs could be quite favorable.