Taser stun guns have a big design problem

Kimberly Potter, the 26-year police veteran who fatally shot Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in Minnesota on April 11, has been charged with second-degree manslaughter. Prosecutors will be tasked to prove to the courts that she was negligent in drawing and firing her Glock pistol instead of her Taser stun gun when subduing the 20-year old.

Kimberly Potter, the 26-year police veteran who fatally shot Daunte Wright during a traffic stop in Minnesota on April 11, has been charged with second-degree manslaughter. Prosecutors will be tasked to prove to the courts that she was negligent in drawing and firing her Glock pistol instead of her Taser stun gun when subduing the 20-year old.

A widely scrutinized body-cam video shows Potter yelling “Taser! Taser! Taser!“ before firing a bullet into Wright’s chest which killed him on the scene. Beneath what appears to be another appalling accidental shooting actually belies a complex, systemic issue at the core of America’s problematic, hyper-aggressive policing philosophy. This ethos is ultimately reflected in the design of standard tools law enforcement officers carry and how they use them. It’s bigger than an industrial design problem, but it’s certainly part of the issue.

How could a veteran cop—who even served as a training officer—mistake a stun gun for a pistol? Many speculate that it has something to do with the physical similarities between the two objects Potter allegedly mixed up. Both the Taser and the gun, for instance, are held via a pistol grip. It’s a form in tools such as power drills, gasoline pump nozzles, and even the now ubiquitous body thermometers at Covid-19 check points. “It’s ergonomically simple and it’s an ideal shape for a trigger finger to depress a button,” explains Pascual Wawoe, director of the undergraduate product design department at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena.

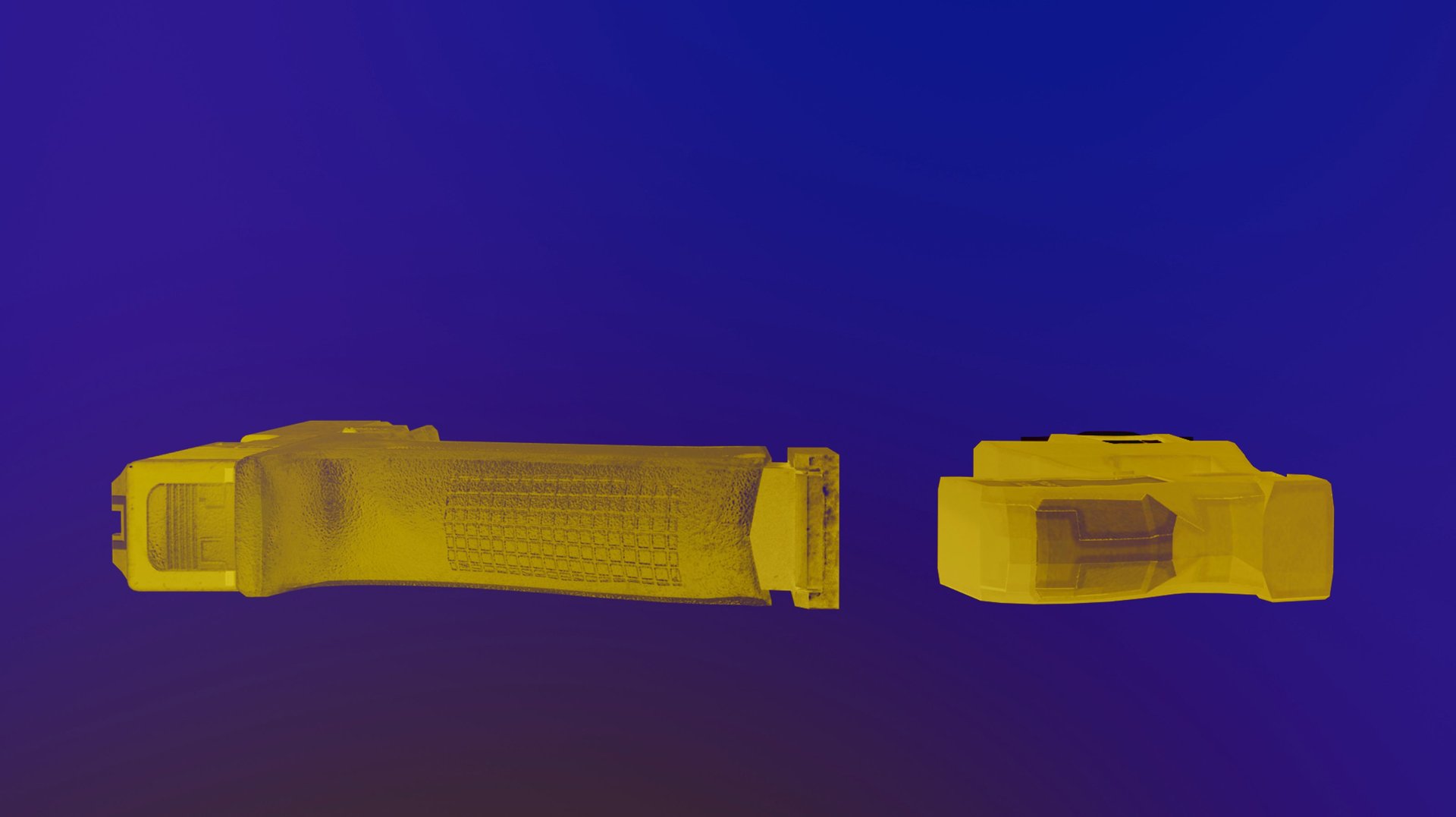

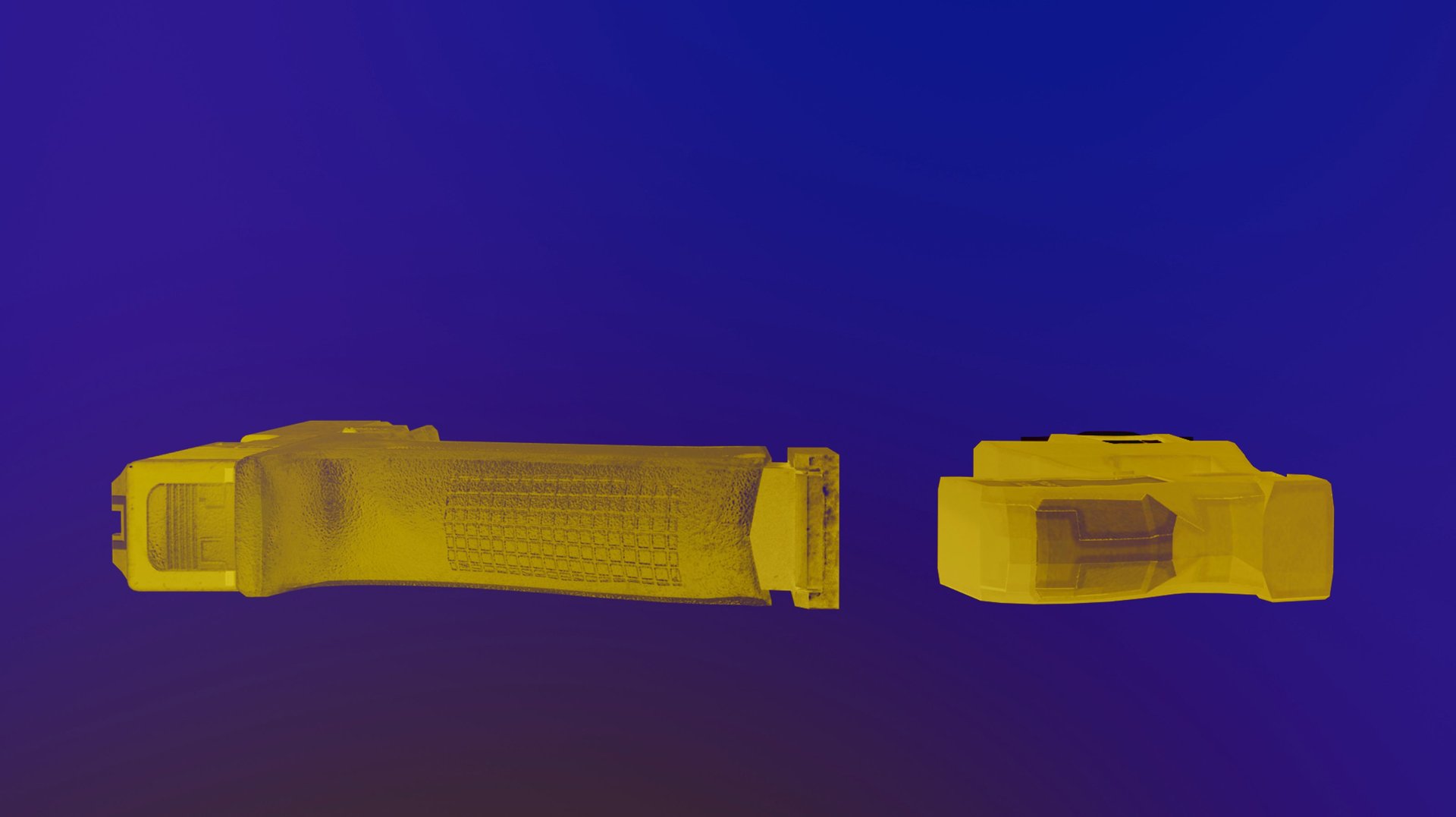

Tasers have a different grip and weight than guns

Axon Enterprise, the manufacturer of the Taser brand stun guns used by most police departments in the US, told Reuters that they’ve worked to incorporate differentiating features such as developing a different grip and making them a different weight than firearms. Most of their Taser models—but not all—come in bright yellow to contrast with the black color of police hand pistols.

Many experts, including Wawoe, believe that’s not enough. “A better solution would not look like a handgun or shouldn’t feel like one,” he argues. Maria Haberfeld, a professor of police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice concurs that it’s partly an industrial design problem. “The Tasers and guns are indeed too similar in their shapes and should definitely be designed differently to minimize the confusion aspect that can occur during stressful situations,” she tells Quartz.

Cases when a cop confused a Taser for a gun are rare, but they do happen. According to the Star Tribune’s research, there have been 11 court filings that involves a police officer accidentally firing the wrong weapon since 1999—the year when Taser International introduced its first pistol-shaped model called Advanced Taser M26. Of those instances, three people died. The company changed its name to Axon in 2017.

The most commonly cited reason for the error is lack of training. “You cannot control what people will do during the traffic stop,” Haberfeld explains. She says recruiting qualified officers and training them is key. “Reinforcing their communication and tactical skills with more frequent and scenario-based approach [drills] needs to be introduced in a much more frequent manner.”

But experts also contend that the design of Tasers also needs a major rethink.

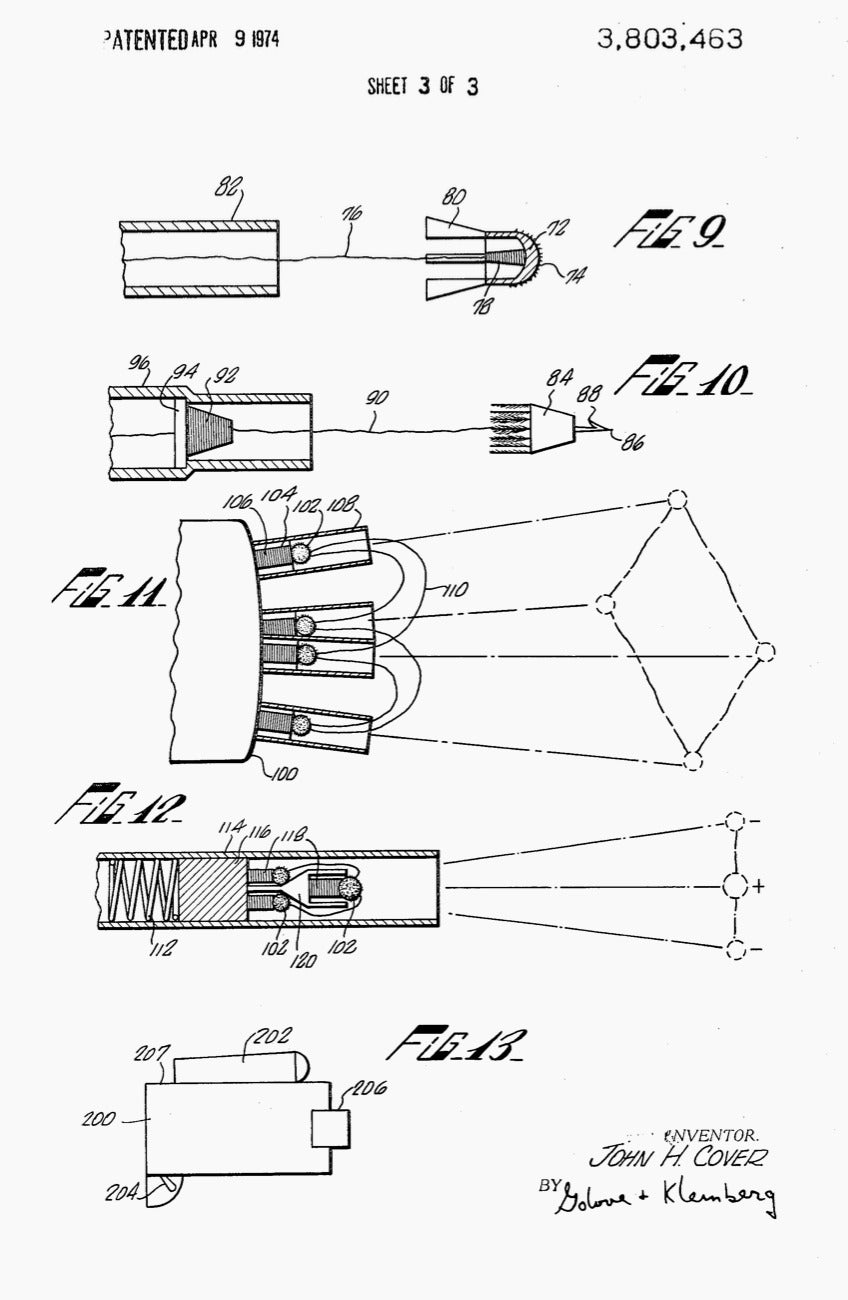

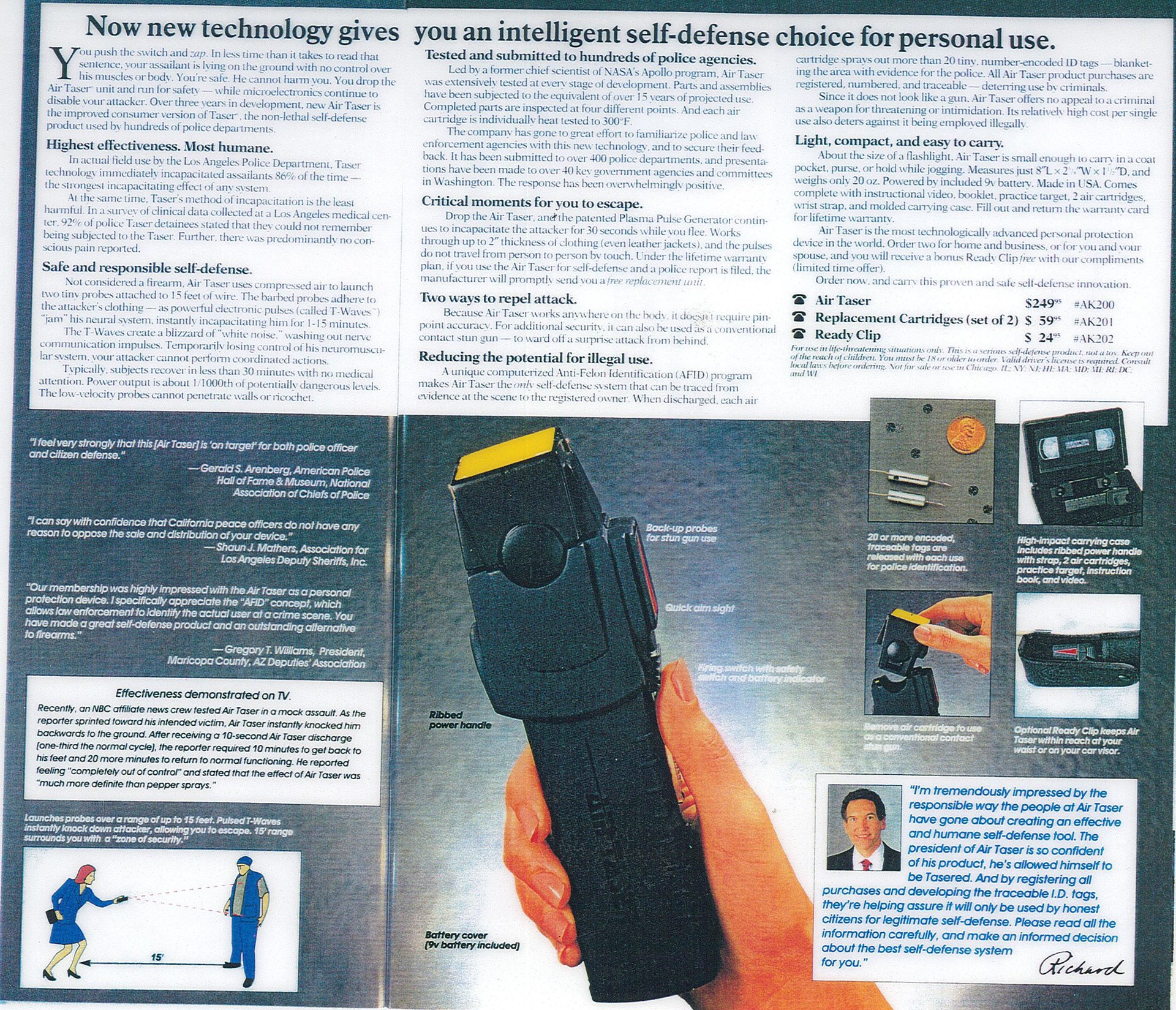

The history and evolution of Tasers

Tasers didn’t always look like guns. When physicist Jack Cover first introduced his invention in 1974, the “weapon for immobilization and capture” as he called it in his patent application looked more like a flashlight. Named after his favorite childhood novel, “Thomas Swift Electric Rifle” (Cover apparently added an “A” later because he “got tired of answering the phone ‘T-S-E-R’”), police officers celebrated the device as another tool that could help them apprehend suspects without having to fire a gun. “The general principle of escalation of force by law enforcement consisted of the following continuum: verbal control, hand control, handcuffs, mace, batons, and finally firearms,” wrote William C. Plouffe in the Encyclopedia of Race and Crime. “The huge gap between the use of the baton and the use of a firearm presented problems for law enforcement.” After he solved an engineering issue, replacing gunpower with compressed nitrogen, Cover’s Taser guns became particularly popular for marshals aboard airplanes.

Over the course of their evolution, stun guns have also resembled TV remote controls, pen lights, tubes of lipstick, or even electric shavers as seen in a 1995 entry in the Sharper Image catalog.

In 2019, a “Spiderman-like lasso” restraint device called Bolawrap was proposed as an alternative to stun guns.

In the late 1990s, Tasers eventually mimicked the shape of handguns, as we know them today because the pistol-grip, “L-shape” design had been found to be the most intuitive. “We design things as extensions of our own bodies,” explains Glenn LaVertu, an industrial design professor who studies the role of design and technology in the US gun control debate. “Guns, drills, thermometers, Tasers, and a whole host of other tools are meant as an elongation or surrogate of ourselves.”

LaVertu says the L-shape became a classic among industrial designers because it’s essentially an extension of our hands. “Power tools with a grip ensure that the user has a strong hold of the tool so that it can perform its task efficiently,” he explains. “The same is true for firearms with the additional need to maintain accuracy during the firing and an ability to hold a control the gun as the ignition kicks-back. Other objects with this L-shape perform different tasks but all have the same design concern in mind: aim and control.”

The neuroscience of Taser user error

Charles Mauro, a humans factors expert and president of Mauro Usability Science, was horrified to hear about the tragic events in Minnesota, that he believes, could’ve been avoided had there been better understanding of how the human brain processes information in high stress situations.

The shape of a Taser is similar to a gun

“This is not a new problem. It is very clear to me that based on an actual detailed understanding of how the human information processing system deals with objects in the real world, we learn that what may intuitively appear to be two products that are substantially different, in fact, aren’t experienced that way—especially under high levels of stress,” he explains. “This is very well understood in cognitive neuroscience.”

Mauro, who developed a neuroscience-based approach for design research and product testing, points to a classic human factors precept called “Just Noticeable Difference,” which measures how well the humans can detect differences between two like objects in a meaningful way. Without distinct differences, a user mistaking one object for another during high-stress scenarios are more likely to occur. It’s an error known as “slip and capture.”

The way Police carry guns and Tasers can be confusing

Beyond the shape of Taser guns, a policeman’s packed duty belt is also a contributing factor. “When you attach all manner of objects to a belt, it’s just straight up confusion theory that predicts that the response time is going to go down and confusion is going to go up,” explains Mauro.

Wawoe also thinks the placement of the stun gun vis-a-vis a service firearm needs to be swapped. Police officers in the US are trained to keep their firearm within easy-reach of their dominant hand and Tasers are placed on the side of the weak hand. Wawoe says switching their positions could make a profound difference. “I think that the lethal weapon should be the one that is the hardest to reach,” he argues. “To reach for a firearm, you have to make a very deliberate decision.”

‘I think a firearm should literally be a last resort,” says Wawoe who grew up in the Netherlands. “This is how the police in other Western industrialized countries they treat the firearm, for example. They literally use it as the last step; they don’t pull their guns in a traffic stop. But they also have the luxury of also knowing that the odds are extremely low that a passenger or a driver is armed,” he points out. That luxury doesn’t exist in the US where its Constitution establishes a right to own firearms.

Expert users make very different mistakes than beginners

And how could an experienced cop like Potter make such a blunder?

Mauro explains that it’s precisely expert users who make these types of missteps. He says, expert users make very different types of mistakes from beginners. “The most experienced users employ heuristics in their decision making. That means that they have so much experience that they are likely to take shortcuts.” In this case, it appears that Potter may have reached for an instrument that felt like a Taser without looking at it, trusting the number of times she’s done it successfully.

“The bottom line is that when it comes to evaluating products that are life-determining, human intuition is often inadequate,” says Mauro. “The underlying neuroscience often leads to counterintuitive solutions and insights.”

A clamor for better design and better-designed systems

Wawoe explains that good product design has to be “intuitive, obvious, and idiot-proof.” The more consequential or potentially life-threatening it is, the more scrutiny and testing it requires, he says. “Designers must anticipate the worst case scenario of a product,” says Wawoe. “That level of safety or ‘idiot proofness’ goes up with certain products like medical equipment or weapons, in this case.” Good designers, he argues, don’t just design the product, they also think through all the use case scenarios. Beyond finessing the shape of objects, it’s also about improving the system around it.

“It’s a systems problem,” Mauro observes, “[It’s] a combination of training, product design, learning about user biases… the pressure and stress of the situation has a dramatic impact on human information processing too.”

Mauro contends since its invention in the 1970s, that Tasers haven’t undergone sufficient user testing for such a widely-used weapon. “What I can say with clear confidence is that the development of these devices has not undergone any level of serious human factor science,” he points out.

Wawoe calls the pistol-shaped Taser’s form “lazy design.”

“The primary design objective for a Taser is to essentially make it easy to understand functionally by making it as close as possible to a handgun,” concurs Mauro. “It’s a mapping of one design on to another. Whenever you do that, you’re almost guaranteeing that you’re going to have a classification error.”