Why Joe Biden’s multibillion-dollar vaccine aid pledges are meaningless

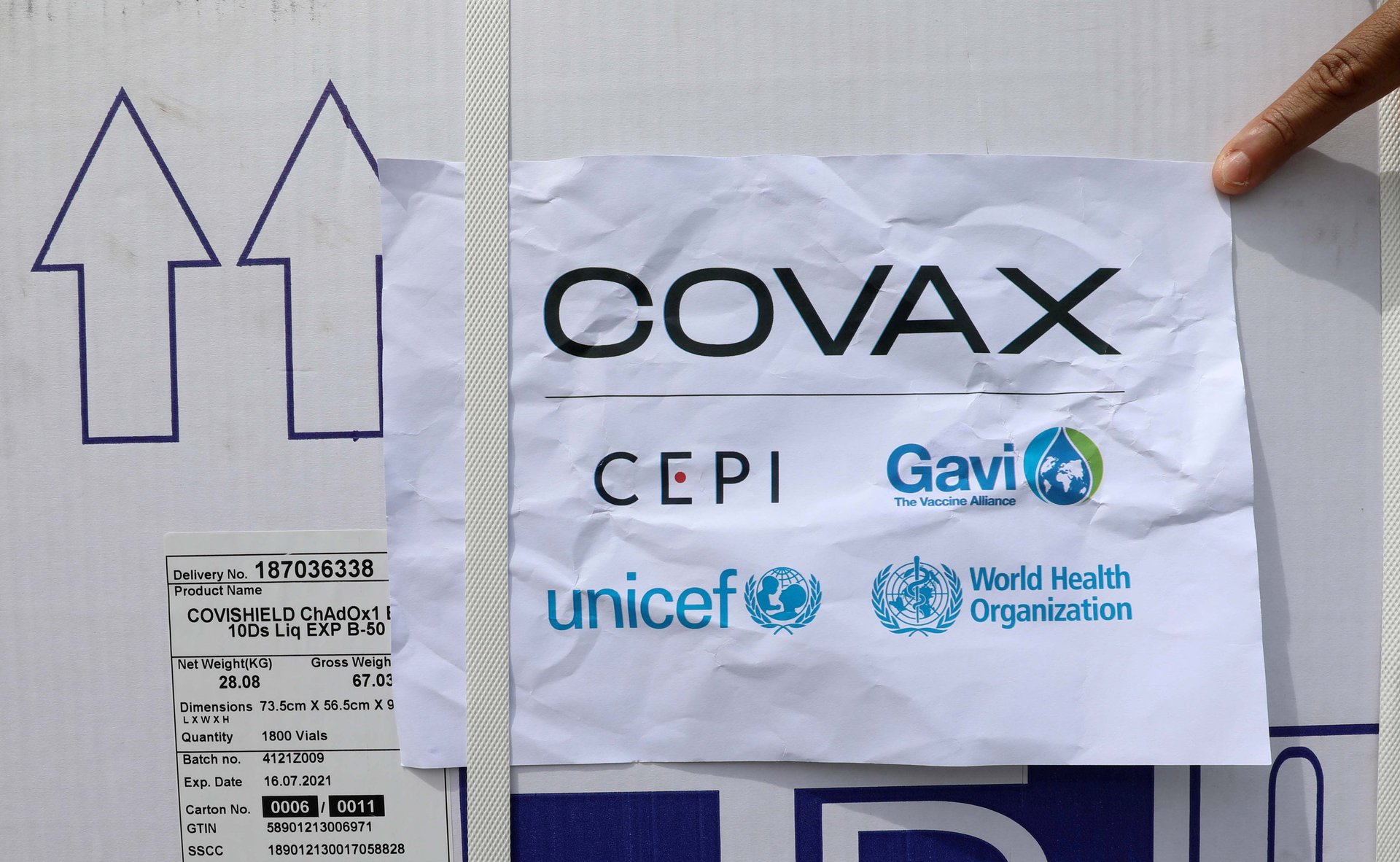

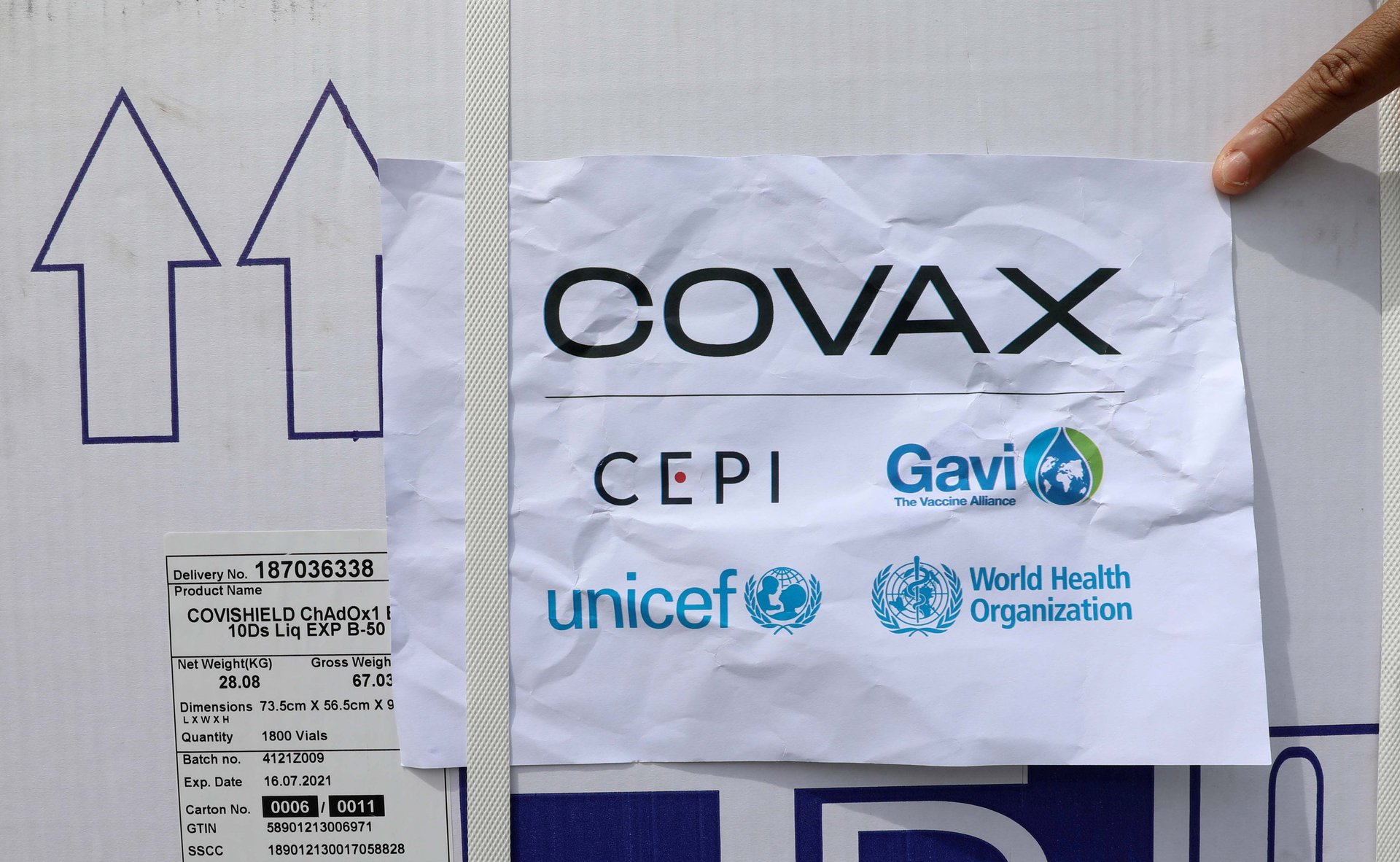

In February, weeks after president Joe Biden took office, he announced $4 billion in funds for Covax, a multilateral drive backed by the World Health Organization to pay for vaccines for developing countries. Last week, Anthony Blinken, the US secretary of State, headlined an online fundraiser to rustle up an additional $2 billion from private donors. “This isn’t just an opportunity,” Blinken said, “it’s an imperative.”

In February, weeks after president Joe Biden took office, he announced $4 billion in funds for Covax, a multilateral drive backed by the World Health Organization to pay for vaccines for developing countries. Last week, Anthony Blinken, the US secretary of State, headlined an online fundraiser to rustle up an additional $2 billion from private donors. “This isn’t just an opportunity,” Blinken said, “it’s an imperative.”

But the way the vaccine procurement process is set up, these donations are meaningless: a whole lot of cash that buys nothing. Worse still, these funds constitute a reprisal of the biggest mistakes of traditional foreign aid programs—the kind based on the quintessential American belief that money will solve everything.

For one thing, the dispersal of this money still will not allow poorer countries to secure vaccines—because there aren’t many vaccines to buy, at the moment. “The world’s wealthiest nations have locked up much of the near-term supply,” a new report authored by Duke University scholars points out. For their population of 1.2 billion, the wealthier nations have booked themselves 4.6 billion doses, so the manufacturing capacity of vaccine firms will be locked up for months to fulfill these orders.

Canada has been a particularly egregious offender. For its population of 37 million, it has struck agreements to buy up to nearly 400 million doses of vaccine. This includes 1.9 million doses from the Covax pool intended for poorer countries.

If these countries have any surpluses at all, they’re holding on to them. The US will have roughly 300 million extra doses by July, according to the report—enough to vaccinate several small countries that have been told to expect delays in their Covax vaccines. Yemen needs 60 million doses to inoculate its population, for instance; South Sudan needs 22 million, Mauritius just 3 million. Yet the Biden administration has announced no plan to donate its spare vaccines. “At the current rate,” the Duke report estimates, low-income countries “may not reach 60% coverage until 2023 or later.”

Trade, not aid

The Western custom of doling out money as aid has frequently been criticized for the way it works in practice. Often, the funds are “tied”—pre-committed to buy products from the country that disburses them. Developing nations struggle to progress from being recipients of charity to productive economies, in part because the global marketplace is stacked against them.

Thus the popular slogan “Trade not aid” is sometimes a free-marketeer’s credo, but it is also a call by activists from the Global South to make world trade fairer. Joseph Stiglitz, the Nobel-winning economist, noted that the US is guilty of erecting some of these barriers to fair trade. “Vietnamese catfish are not allowed to go by that name, as their low price undercuts American catfish,” Stiglitz once wrote in the Financial Times. “Steel imports from efficient producers in Asia are kept out of the US. As Russian aluminium entered the US, the US created a global cartel to limit the inflow.”

Covax holds a strong parallel to this situation. Nearly 100 developing countries petitioned the World Trade Organization to temporarily waive intellectual property protections on vaccines during the pandemic, so that they could manufacture generic vaccines domestically. The US, the UK, and the European Union have all blocked this move. Even without IP waivers, the US could fund and support temporary licenses for the vaccine to be manufactured in more places around the world, the authors of the Duke report wrote. That wouldn’t just boost the supply of vaccines; it would also help other countries acquire some of the technical know-how required to build their own vaccine sectors.

As it stands, the money poured into Covax only buys a drip-feed of vaccines for developing nations. And it ensures they stay dependent on the companies and countries of the West. When the next pandemic strikes, they will have to depend once again on Western benevolence, and then wait their turn until North American and European countries are satisfied that their own citizens are safe first.