Spewing sewage into the ocean is bad: toxic algae and man-sized jellyfish edition

Once a swampy backwater of fewer than 20 million people, the Pearl River Delta—the southern swath of mainland China above Hong Kong—now has three times that population. Tens of millions more humans in the Pearl River Delta means many more toilets a-flush, pumping a steady gush of human waste into the South China Sea.

Once a swampy backwater of fewer than 20 million people, the Pearl River Delta—the southern swath of mainland China above Hong Kong—now has three times that population. Tens of millions more humans in the Pearl River Delta means many more toilets a-flush, pumping a steady gush of human waste into the South China Sea.

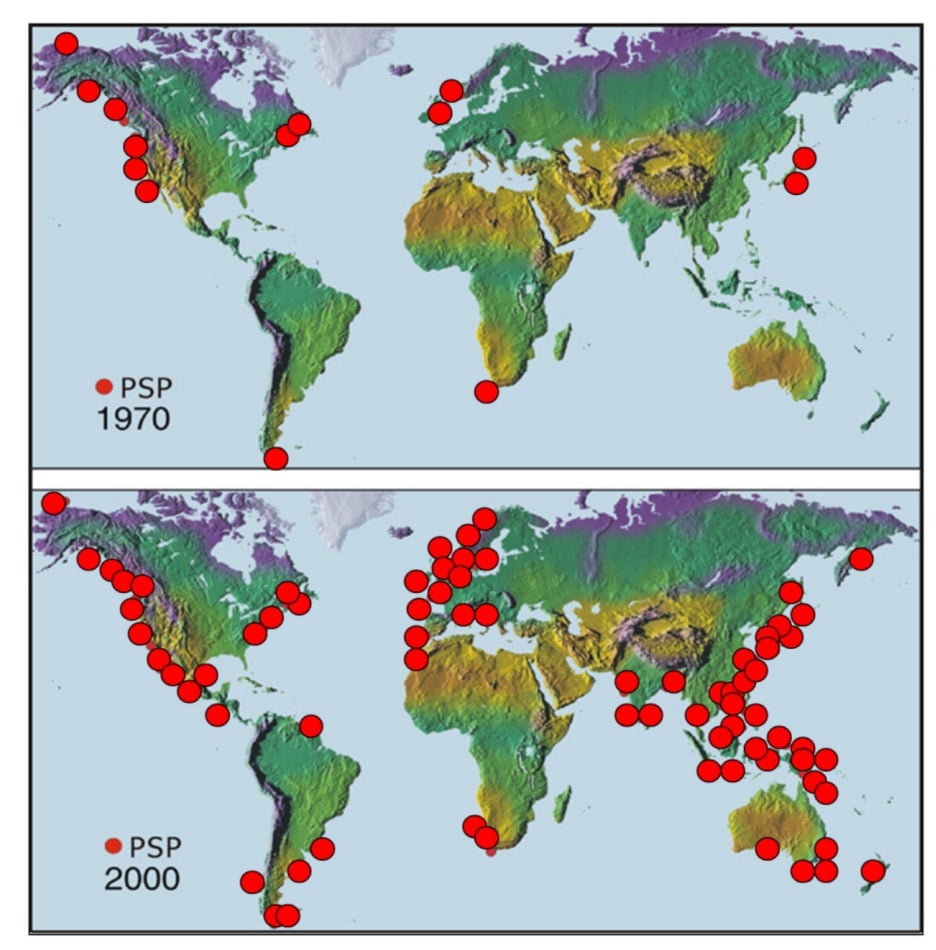

That’s gross—but not necessarily for the reasons you might think. That nutrient-packed sewage is an all-you-can-eat buffet for algae. And since some of those can be toxic to humans, sea mammals, and fish, these algae blooms are a big headache for Hong Kong officials, reports the South China Morning Post (paywall). They’re not the only ones. Scientists are increasingly worried that the causes behind algae blooms are wreaking permanent change to surrounding ecosystems.

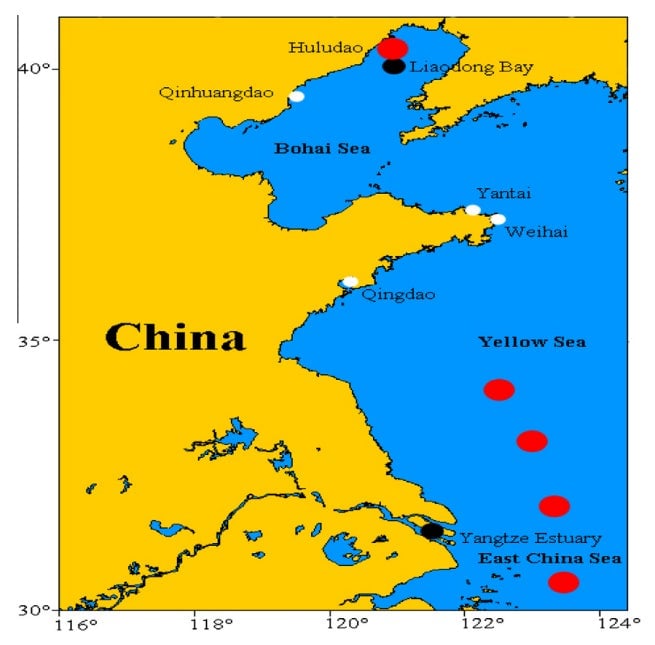

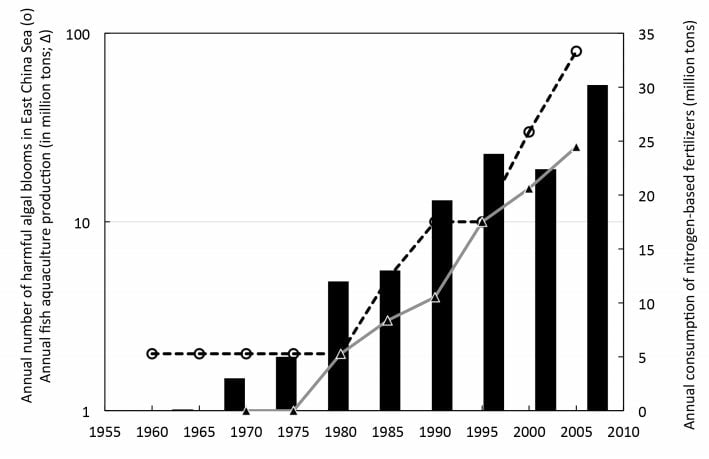

In fact, all along China’s coasts algal blooms are bursting more often and more intensely. It’s not surprising; as China’s coastal provinces have powered the country’s economic juggernaut, their populations surged from 243 million in 1952 to more than 700 million (pdf). The agriculture and aquaculture needed to feed these teeming masses add still more organic matter to the streams of waste spilling out of China’s big deltas—the Pearl River, Yangtze and Yellow—and into the sea. Because this waste is packed with nutrients such as phosphorous and nitrogen, which provide a cornucopia for algae gluttony, big algal blooms appear to track with booming coastal populations and economic activity.

In July 2013, the biggest algal bloom ever recorded in China covered 28,900 square kilometers (11,158 square miles) of the Yellow Sea—meaning more than three New York City metro areas of ocean was carpeted in green muck—requiring Qingdao city officials to bulldoze 7,335 tonnes (8,085 tons) of beached scum. A similar incident almost shut down the sailing competition of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games. The army dispatched 15,000 soldiers to remove 1 million tons of algae, costing more than $100 million (pdf, p.9).

The algae’s effect on fish populations varies. Some algae are toxic, killing valuable fish—a big worry for commercial fishermen as well as for China’s fish-farming industry, which contributes more than two-thirds of global aquaculture output. For instance, a particularly nasty ”red tide,” as one type of toxic algae is called, killed 80% of Hong Kong’s fish farm stock in 1998.

But the algae that don’t kill fish make them stronger—or fatter, at least. And more plentiful. As little fish chow down on more algae and grow their populations, big fish chow down on more of those little fish—exploding the food chain.

Then come the “dead zones.” As dying fish, fish excrement, and algae sink to the bottom of the ocean, they strip the water of oxygen. (See this fantastic infographic for more.)

Most aquatic life can’t live in water so O2-scarce. But as we’ve discussed before, jellyfish can. Once they appear, jellyfish tend to settle in, keeping fish from returning by eating their food and polishing off their eggs. Scientists think this is a major factor behind explosions of the moon and lion’s mane jellyfish—as well as the man-sized Nomura’s jellyfish—off China’s coasts. Some warn that if nothing changes, this jellyfish takeover could change China’s marine ecosystem for good (paywall).