Inside the hard business of selling DIY rape kits

After Madison Campbell was sexually assaulted, she had an overwhelming feeling of not wanting to be touched by anyone, she remembers.

After Madison Campbell was sexually assaulted, she had an overwhelming feeling of not wanting to be touched by anyone, she remembers.

She didn’t want to tell her friends what happened, she didn’t want to talk to the police, she didn’t want to leave her dorm room ever again. In the hours that followed the crime, which occurred while she attended a study abroad program at the University of Edinburgh in 2016, she walked to a nearby pharmacy to buy black dye for her blond hair, and spent the following days and weeks rewatching Westworld.

Years later, it wasn’t just the assault that haunted her—it was the fact that she had no evidence it ever happened. “I had no text messages, no photos saved. I didn’t save my clothes. I didn’t save anything. And so it would have been my word against his,” she told Quartz. “It’s really disgusting to me that I didn’t feel like I can get any sort of justice because I had I had nothing to prove that it happened.”

To change that, the now 25-year-old, Las Vegas-based entrepreneur founded a company to make the one thing she wishes she had right after she was attacked: A rape kit that she would be able to take at home.

In 2019, together with co-founder Liesel Valdya, Campbell founded MeToo Kit, a company named after the #MeToo movement that had raised her awareness about how tragically common her experience was. The kit included a bag for clothing and a container for saliva, cheek, and genital swabs. “Swab. Spit. Seal,” read the prototype packaging.

But rather than being welcomed, Campbell’s innovation raised concerns and even outrage among legal and medical experts, as well as many survivor organizations. Accused of profiting from rape and selling victims on false hope, the company has received cease and desist notices and legal threats. Yet its founder remains convinced of the need for a more private alternative to the traditional forensic examination.

How rape evidence is collected

Rape is far too commonplace. Nearly half a million people in America are victims of rape or sexual assault, and one in five women will be raped or suffer an attempted rape in her lifetime.

Still, reporting it is rare, with an estimated 23% of rapes and sexual assaults ever reported to the police. Accountability is even rarer: Fewer than 1% of rapists are ever convicted, and even less than that incarcerated.

Despite the high prevalence of rape in our culture, there is little understanding about how a survivor should report a rape, or how the process of pursuing justice works.

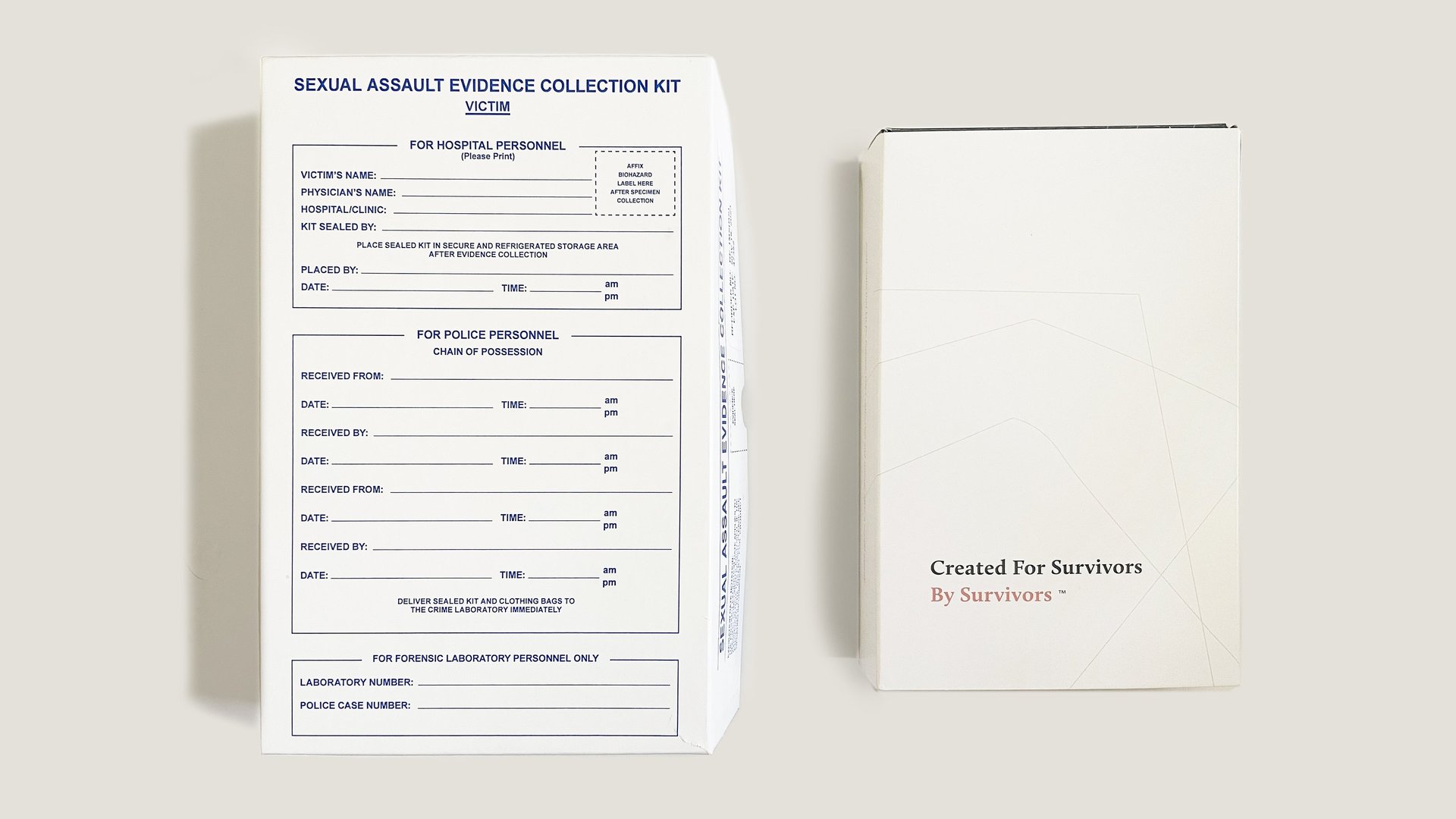

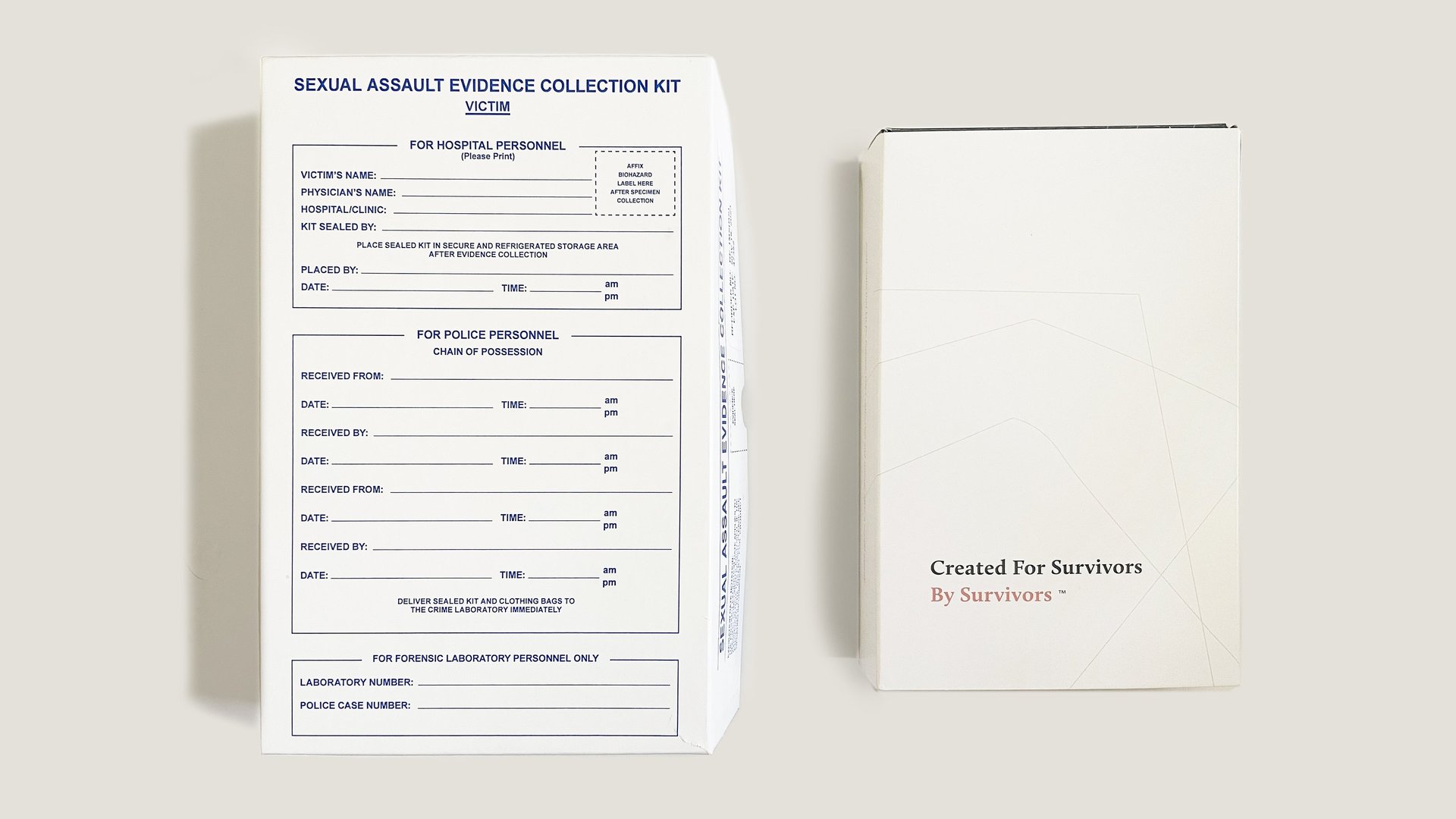

Of the many difficult steps required, one that can be especially traumatic is the sexual assault medical forensic exam, known as rape kit exam. It is typically performed in a hospital or clinic by a trained forensic nurse, who collects evidence of the assault from the body of the victim. It can take several hours, including breaks for the survivor.

Although less than 10% of rape cases ever end up in court, collecting forensic evidence is important to assembling a criminal case. Yet many women don’t report the rape within the three-day window, after which the evidence is usually no longer valid.

But what if a woman could perform the exam on herself, perhaps guided remotely by a nurse, and collect the evidence?

A DIY, at-home rape kit

In August 2019, MeToo Kit joined Alchemist Accelerator, a company investing in the development of early-stage startups. The startup incubator cut the first check to the company, whose first order of business was to figure out a financially sustainable model that didn’t make victims pay for the kits. One idea was that institutions such as universities might want to buy them, and give them to their students both as a way to increase reporting of assault and as a dissuading mechanism—perhaps, thought Campbell, knowing that every woman on campus had a DIY rape kit in her dorm might stop potential rapists.

To check whether colleges might be interested in purchasing the kits for students, Campbell mailed several of them introducing her product and the idea. One email, she says, was sent to the University of Michigan. From the university, her email made it into the hands of Michigan attorney general Dana Nessel.

Although the company was based in Brooklyn, New York, Nessel filed a cease-and-desist notice against the company, accusing it of misrepresenting the product and misleading victims into thinking the DIY kits were sufficient to collect all rape evidence.

New York’s attorney general followed, including another at-home rape kits maker in its notice, PRESERVEkits (the company has since closed). Other states’ attorneys general also questioned the product. Forensic and medical experts blasted the kit, and so did many survivor associations, and women’s rights groups. A group of members of Congress signed a letter expressing concerns about the product.

The accusations were multifold and started right with the name, which was seen as an appropriation. “This company is shamelessly trying to take financial advantage of the ‘Me Too’ movement by luring victims into thinking that an at-home-do-it-yourself sexual assault kit will stand up in court,” said Nessel in presenting her cease-and-desist letter.

MeToo Kit was accused of selling false hope, giving victims the misleading belief that a DIY kit would stand as evidence in a court of law, or that DNA evidence collected from their body is all they need to prove the rape happened. Medical professionals raised concerns that by encouraging victims to self-administer the test, they would be dissuaded from seeking medical attention, including psychological support.

“A forensic exam is something that takes a […] skill set to do well. And we know this because you can look at the data that shows the contrast between evidence that’s collected by a general provider who was handed a kit and told to do this, in contrast to the evidence that’s collected by a sexual assault nurse examiner,” says Mariá Balata, who directs advocacy at Resilience, an Illinois-based rape survivor support organization.

Balata notes that alongside evidence collection, victims are offered counseling, guidance, and assistance—all of which can be as or more important than the examination itself.

On top of it all, MeToo Kit was a for-profit startup. It was backed by venture capital. It had sleek branding. This added a whole different dimension to the controversy—it wasn’t just that the kit wouldn’t collect admissible evidence, and might prove counterproductive. It was that the company was going to make money out of it. “It seems implausible that a company would look to profit from a sexual assault, while also risking the loss of justice for victims, but that is exactly what MeToo Kit Company is doing,” Day One, a sexual assault prevention organization, said in a statement in 2019.

“It is concerning that there are profits to be gained from someone’s sexual assault” says Balata. “There’s all kinds of ways in which these funds could better be used or to invest in prevention work.”

From MeToo Kit to Leda Health

Campbell was undeterred. She continued to believe the kit was one way to improve the system of reporting rape, one that even those who criticize her admit is faulty. It might be especially useful for young women or victims who don’t feel comfortable reporting, for instance out of fears related to their immigration status, she says. “The 77% [of victims] nationwide, 90% of folks on college campuses not reporting—that seems like a large population that needs something different,” she says.

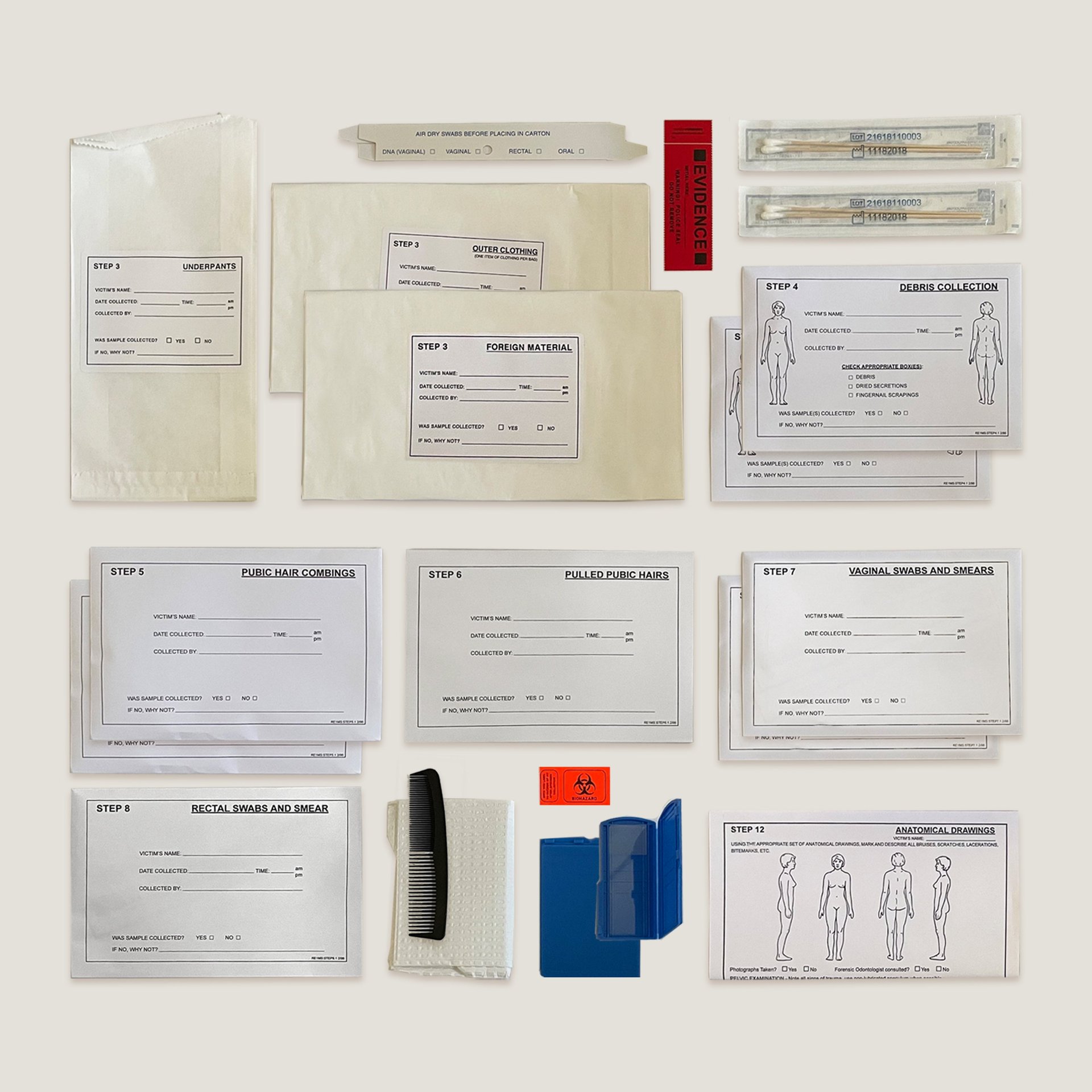

She absorbed a lot of the criticism, realizing her naiveté—as a startup founder, and one working in such a sensitive space—had led her to make mistakes. In early 2020, the company’s name was changed to Leda Health, after the Greek myth of Leda, who was raped by Zeus, and created a new design, incorporating some of the feedback, as well as new insight from forensic nurses, into the kits.

Since the beginning, getting funding was easier through venture capital and private funds than through government grants and non-profit avenues, which Campbell said aren’t enough to fund innovations like hers. So far, the company has raised over $2.2 million from a range of private and institutional investors. “When you look at the nonprofit space for sexual assault survivors, there is not a single dollar that can be spent on anything other than critical services,” Campbell says.

The journey to funding wasn’t easy, but one thing unexpectedly helped Leda Health’s case: Covid-19.

Prior to the pandemic, despite the founder’s conviction, the expert consensus seemed to be that there was no way for DIY rape kits to rise above the many challenges they presented. Their forensic value, in particular, was criticized in part because the chain of custody of evidence might be compromised.

But in April 2020, with a shortage of medical personnel and hospitals discontinuing non-essential services, Monterey County in California occasionally began accepting self-administered rape kits. The evidence was collected under the remote guidance of a forensic nurse, and specific custody requirements ensured the evidence would be valid.

Although it was a temporary protocol, it showed an opening. At-home rape kits could potentially be accepted by the police—because they had been.

Are at-home rape kits helpful, or dangerous?

Still, the controversy on whether a DIY kit could and should exist, and if it could be helpful for victims or detrimental to their health, is very much alive.

“Companies that promote and sell do-it-yourself sexual assault kits are undermining the necessary steps law enforcement must follow in order to properly investigate and prosecute these heinous crimes,” Lynsey Mukomel, press secretary to Michigan attorney general Nessel, wrote in an email to Quartz. “Our message to survivors is clear: You are not alone. There is support out there to help you that won’t be found in an at-home kit.”

The International Association of Forensic Nurses (IAFN), is strongly opposed to at-home rape kits. “As forensic nurses, our primary concern is the patient’s health. These at-home kits provide no healthcare benefit,” reads the IAFN website on a page dedicated to warning against their use. In March 2020, the IAFN, while acknowledging the pandemic had reduced the likelihood of seeking medical care after a sexual assault, rejected the idea that at-home rape kits could be a solution.

Even post Covid-19, RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), the largest anti-rape organization in the US, continues to be against them. “The evidence collected through [at home rape kits] is generally not admissible in court, so RAINN does not endorse them,” Erinn Robinson, a spokesperson for the organization, told Quartz.

However, the Academy of Forensic Nursing (AFN), the other main forensic nursing organization in the country, considers the idea of DIY kits a welcome innovation. “I look at this and think that’s a great idea,” says AFN’s former president Diana Faugno. “I think if we incorporated some telemedicine and we’re able to speak directly to the patient, and if that’s what they wanted, we can help them with the collection and offer treatment,” she says.

There are several reasons Faugno believes it’s worth working on DIY kits to make them acceptable as evidence. One is that they could help solve an overlooked capacity issue. “If we had all of those women and men who were sexually assaulted come into hospitals and report a sexual assault and expect an evidence collection kit, we would be overwhelmed,” she says.

But Faugno also puts the issue of reliable evidence collection into context. “As a forensic nurse, I get a lot of evidence handed to me by the patient in a plastic bag. Whether it’s clothing or q-tips that she got from the hotel she was in, I always accept that evidence,” she says. “That’s part of the kit. So I don’t think the police would not accept a [DIY] kit—they’re used to that,” she says.

She considers the argument that the evidence wouldn’t be valid in court less important, too. “Every case would determine what evidence would be admitted and what evidence would not,” she says. In the few cases that end up in court, Faugno notes, even professionally collected evidence may not be accepted, or be irrelevant because in most cases the perpetrator claims the sexual encounter was consensual but doesn’t deny it occurred. Further, she said, victims might use the kits for civil proceedings, or to help get disciplinary measures enforced at institutions like universities.

Fundamentally, the questions raised about the DIY kit are part of a bigger issue—about trust in women. Considering how many rape cases are essentially come down to “she said, he said,” disqualifying self-collected evidence seems like just another way to question the victim’s intentions, and truthfulness.

A controversial business model

Although the pushback against the at-home rape kits continues (in January, Utah state legislators introduced a bill banning them), Leda Health has moved forward. Currently, no kits are in use, but new prototypes have gone out for review to get feedback from survivor advocates, healthcare professionals, and legal experts, and are being updated to incorporate their feedback.

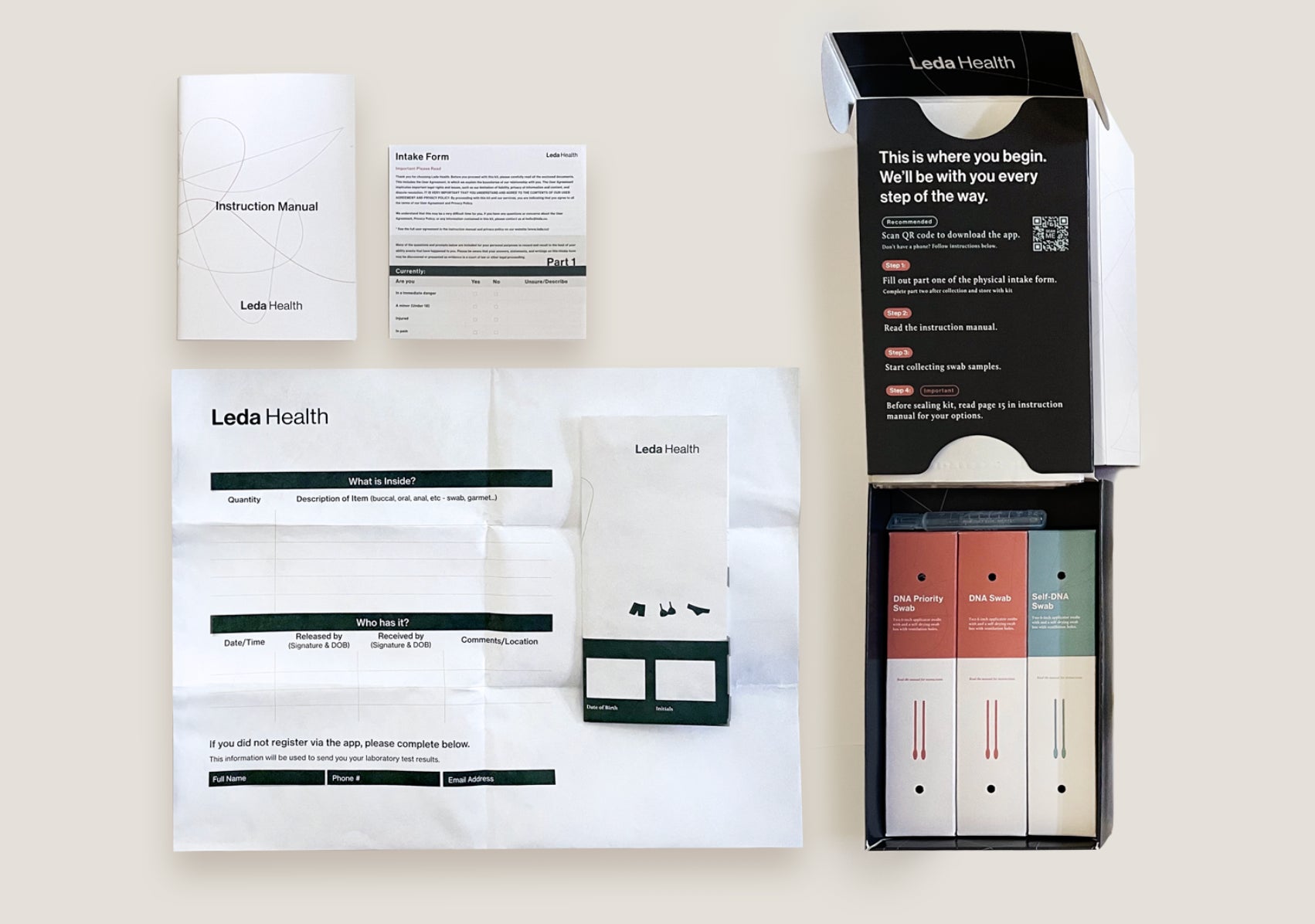

Like the previous MeToo kits, these new ones have a sleek design that stands out compared to the standard rape kits issued to hospitals. The box reads “Created For Survivors, By Survivors™”. Inside it, friendly step-by-step instructions explain how to use the various swabs and bags provided to preserve the evidence.

They are, in other words, a marketing-friendly product, and now just one part of the company’s offering—Leda Health has expanded its plans and is beta testing what is essentially a telehealth company for rape and sexual assault survivors.

“We really wanted to create a holistic healthcare solution,” says Campbell, listing the features that will be offered by Leda Health, which include emergency contraceptives, prophylaxis, and treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, and even personal support groups.

The company is focused on partnering with colleges and universities, which would pay for the services for survivors. Ideally, says Campbell, other institutions would follow, providing access to Leda Health for the disadvantaged communities—including immigrants and people of color—who tend to be overrepresented among rape victims. “The populations that need these services the most can’t afford them,” says Campbell.

Still, by expanding the range of services it provides, Leda Health could expose itself more to the criticism that it wants to profit from rape and sexual assault, even if not directly from survivors.

But by the same token, don’t all companies targeting specific healthcare needs profit from disease? Isn’t that the mandate behind a private healthcare system anyway—that the market will provide the financial incentive to pursue innovation?

Faugno, for one, thinks blaming a DIY rape kit company for profiting from rape while having no issues with other forensic product makers is unfair. “All the kits are from companies. Whether it’s from the hospital or Erowid [or] Forensics—they’re all making money on these kits,” she says.

For her part, Campbell says being a for-profit company has allowed her to move faster in creating a product she thought necessary, and expand the offering of Leda health. Because she isn’t funded by the same sources as nonprofits, she talks about her company not as a competitor of other organizations working with rape victims, but more as an ally that will eventually be able to support them.

“I really see the future as being alive and being able to say, we have this for-profit entity, we’re getting money from different sources, but it allows us to innovate,” she says. “You know, why not raise capital to solve the world’s biggest problems if we possibly can?”