How the Olympics could get canceled

It’s crunch time for the 2021 summer Olympics.

It’s crunch time for the 2021 summer Olympics.

The games, which are scheduled to take place in Tokyo and other parts of Japan from July 23 to Aug. 8, were already postponed for a year due to the coronavirus. Now, they may be pushed back again, or canceled altogether, as Covid-19 cases continue to rise, not just in Japan, but also across southeast and east Asia.

Opinion polls show that the Japanese population and Japanese firms largely favor postponing or canceling the games, and even some Olympic officials don’t sound confident. But today (May 21), International Olympic Committee Coordination Commission chairman John Coates sought to reassure them. “It’s now clearer than ever that these Games will be safe for the people participating and safe for the people of Japan,” he said. Meanwhile, Tokyo 2020 organizing committee president Seiko Hashimoto confirmed that the number of foreign athletes, staff, media, and members of the “Olympic family” have been reduced by more than half, from 180,000 to 78,000.

Things could still change. And there are important financial, political, and institutional factors at play, as well as historical precedent: The games have only ever been canceled in wartime. Here’s what we know so far.

Who runs the Olympics?

The Olympic Games are a partnership between four main players:

- The International Olympic Committee (IOC), which oversees the Olympic movement and directs funds to organizing bodies.

- The National Olympic Committees (NOC), of which there are 206. They select the athletes that will attend the Olympics, nominate host cities, and promote the Olympics at home.

- The Organizing Committees for the Olympic Games (OCOG), which are formed by the host country’s NOC to organize and run the Olympics. OCOGs report to the IOC.

- The host country and host city, which pay for the bids and finance new infrastructure and public services like extra security and border control officers.

Who gets to cancel the Olympics?

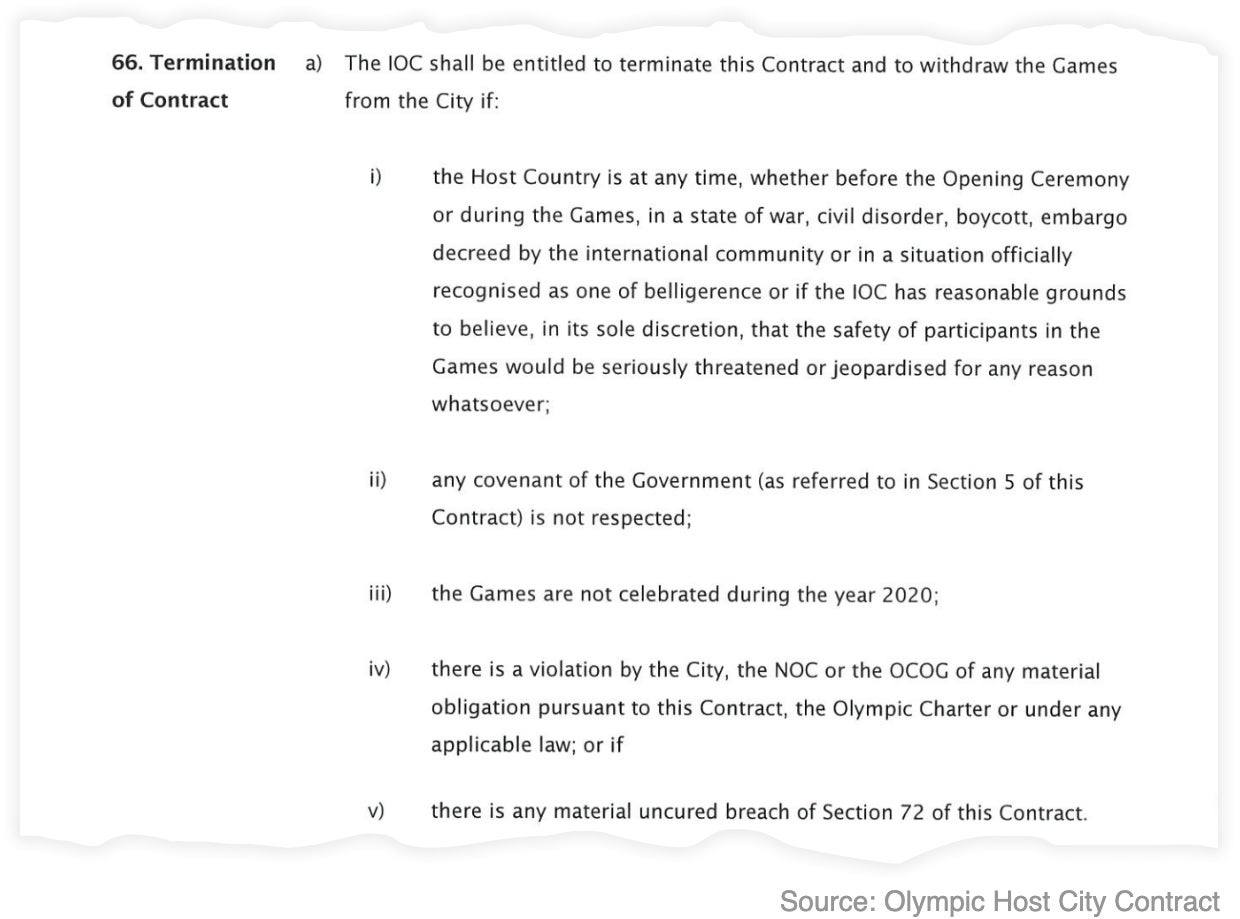

According to the host city contract (pdf, p. 72), only the IOC can cancel the games. Clause 66 gives five reasons for which the Olympics could be canceled. The most relevant one states that the IOC can terminate the contract if it has “reasonable grounds to believe” that “the safety of participants in the Games would be seriously threatened or jeopardized” by attending.

The question is: Legally speaking, does the pandemic at this stage represent a serious threat to participants’ safety?

No one knows for sure, according to Jeffrey Benz, former general counsel of the US Olympic Committee, who points out that the IOC is not alone in weighing this kind of choice because of Covid-19. In 2020, he adds, “everyone started looking at their contracts and whether they had provisions that governed force majeure that would govern pandemics. A lot of people discovered that they didn’t. The general rule is, you have to be very specific about identifying the kinds of things that would give you an excuse to not perform your contract.”

Who has to pay if the Olympics are canceled?

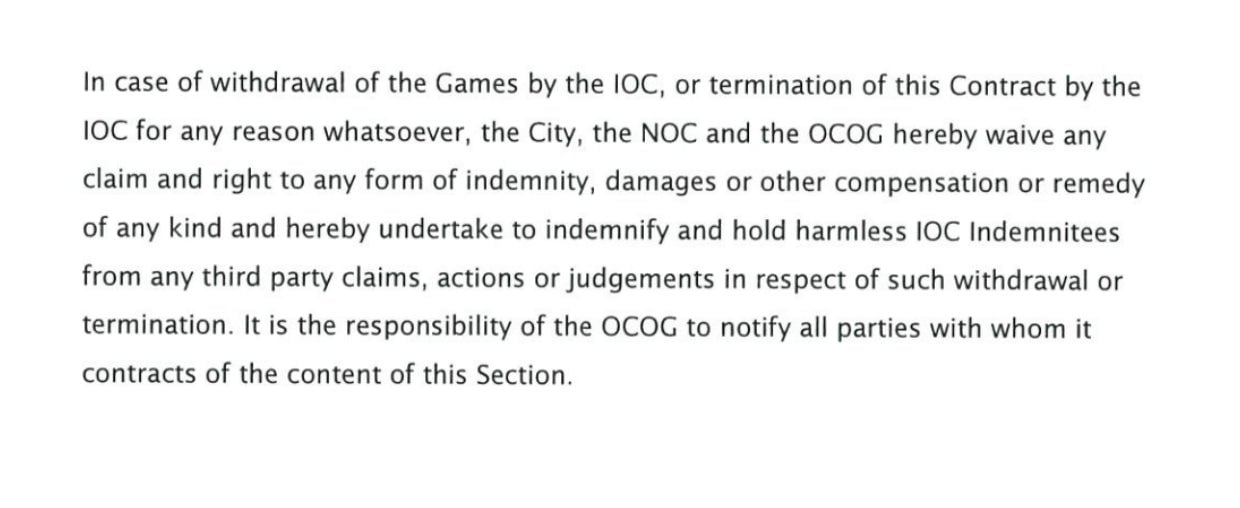

The host city contract is very explicit in answering the question of who pays for canceled Olympics. “If the IOC elects to terminate the agreement, the local folks on the ground end up holding the bag on any losses that flow to them later or any sunk costs that they have [incurred] organizing the games to this point,” says Benz. That includes the city of Tokyo, Japan’s NOC, and its OCOG.

But it’s not that simple. There are also costs associated with The Olympic Partners (TOP), a global sponsorship program managed by the IOC that gives sponsors exclusive global marketing rights and partnership opportunities in exchange for a financial contribution of $500 million. Current TOP companies include Alibaba, Toyota, and Dow (pdf, p. 16).

It’s not clear exactly how the payments schedule has been set up. But Benz argues that “if a lot of money has been paid upfront on the notion that there was going to be a return on investment based on sponsorship of the games, and that doesn’t happen at all, I would imagine there would be a need for the IOC to cure that, legally.”

Reuters reports that insurers could face a “mind-blowingly” large bill of $2 to $3 billion if the Tokyo Olympics were to be canceled.

Broadcasting rights and sponsorships are the money-making parts of the Olympics. Of the IOC’s revenue between 2013 and 2016 (pdf, p.6), 73% came from broadcast rights, and 18% came from marketing rights to TOP partners.

Sponsors make money across a four-year Olympiad, meaning the Summer, Winter, and Paralympic Games. So the key is whether the games take place, even in a limited fashion, says Benz. “As long as eyeballs are watching the events and being subjected to commercials at every suitable break, then the sponsors are getting a lot of what they bargained for.”

Is there a deadline for canceling the Olympics?

The first event of the 2021 Tokyo Olympics is scheduled to take place exactly two months from now, on July 21. How much longer could IOC officials potentially decide to cancel?

Last year, they postponed the games in late March. While there is no official cut-off date, the schedule is tight. Test and qualifying events are under way and some international athletes are already on the ground. Athletes have to quarantine for three days (pdf, p. 21) upon arrival, with some exemptions, and are being asked to keep their contact with other people “to a minimum” during the 14 days before they travel to Japan. “The pain point is increasing every day,” says Benz.

(In an email statement to Quartz, the IOC said it is “fully concentrated and committed to the successful delivery of the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020 this year, and working at full speed towards the opening ceremony on 23 July.”)

As difficult a decision as this is for IOC and Japanese officials, the people who could suffer the most are the athletes caught in the middle. Japan’s biggest sports star, tennis player Naomi Osaka, told the BBC she is “not really sure” the games should go ahead because “if people aren’t healthy, and if they’re not feeling safe, then it’s definitely a really big cause for concern.” Fellow tennis player Roger Federer recently told Swiss television station Leman Bleu that “what the athletes need is a decision: is it going to happen or is it not going to happen?”

While much remains up in the air, one thing is certain, says Benz: “It’s a situation unlike any the international Olympic family has found itself in the modern era.”