Heads up, New York: A near-invincible skin bacterium has invaded your gyms—and your homes

It was just 15 years ago that USA300, a nasty strain of Staphylococcus aureus, first began ravaging the skin of team athletes and military recruits. By 1999, around 127,000 people were hospitalized in the US for infections caused by USA300 and other antibiotic-resistant strains of staph. By 2005, that number had more than doubled, hitting 278,000, prompting public health experts to dub the problem an epidemic.

It was just 15 years ago that USA300, a nasty strain of Staphylococcus aureus, first began ravaging the skin of team athletes and military recruits. By 1999, around 127,000 people were hospitalized in the US for infections caused by USA300 and other antibiotic-resistant strains of staph. By 2005, that number had more than doubled, hitting 278,000, prompting public health experts to dub the problem an epidemic.

Worse, unlike many “superbugs,” USA300 is virulent enough to spread outside hospitals, those traditional hotbeds of antibiotic-resistant staph. That’s why it often infects the flesh of young, healthy people. And with around two-thirds of USA300 substrains impervious to leading antibiotics, it’s potentially life-threatening — and has resulted in more than 1,000 confirmed deaths, according to US public health statistics.

How this freakishly tenacious superbug spreads remains mostly a mystery. But a new study (paywall) analyzing how USA300 mutations vary throughout northern New York City neighborhoods reveals some big clues to its persistence.

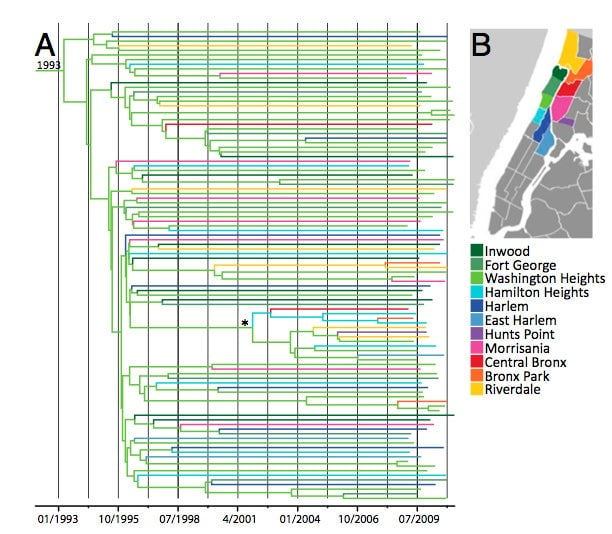

New York City, it turns out, is indeed a melting pot. People have been swapping USA300 substrains up and down northern Manhattan and the Bronx, including substrains from as far away as San Diego and Houston. This implies not only that the bacteria is constantly evolving, but also that it’s handily colonizing both communal areas, like gyms, and people’s homes.

In analyzing USA300’s genetic mutations, Dr. Anne-Catrin Uhlemann, a professor at Columbia University Medical Center and co-author of the study, says she had expected find substrain clusters in certain neighborhoods. Instead, USA300 substrains were so thoroughly jumbled, it was impossible to trace their spread.

The chart below shows the different branches reflect emerging USA300 substrains; the colors show the neighborhoods in which the scientists found those substrains:

The chart reveals another important pattern: when new USA300 started to evolve.

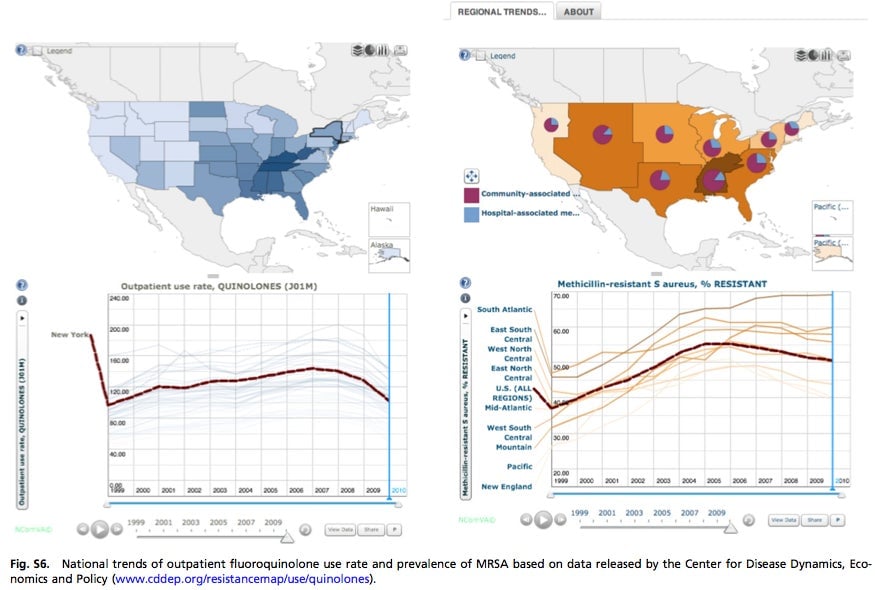

As you can see, branches started breaking off like crazy around the time of the 1995-2002 surge in US consumption of fluoroquinolone—often known as ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin—some 40% of which was for non-FDA-approved maladies. Because fluoroquinolone is secreted through sweat, its comes in contact with way more strains of bacteria than other antibiotics. And that, says Dr. Uhlemann, has given USA300 substrains ample opportunities to adapt.

But after they adapted, how did these new strains spread?

Again, their prevalence makes it hard to tell. Despite the study’s large sample, in only a handful of cases were the researchers able directly to connect an infection in one household to another elsewhere in the community, as you would with, say, the ebola virus, says Dr. Uhlemann.

“[With ebola] you have a case in one village and then the next village—you can almost draw a line from point A to point B to point C,” she says. ”But we’re seeing [USA300] all over—you can’t point to where it came from. It was probably introduced multiple times and then diversified.”

What Dr. Uhlemann and her colleagues did discover is that people from the same household tended to share colonies of the same substrain—a sign that they’re constantly reinfecting each other. They also found cases of multiple types of USA300 in a single household, which Dr. Uhlemann says suggests the presence of an outside reservoir, such as a gym.

There’s some good news in all of this for New Yorkers (and everyone else). Prevalence of antibiotic-resistant staph peaked in 2005, just after the US started kicking its fluoroquinolone habit: