Everything you need to know about ransomware

I. How it worksII. The targetsIII. Case study: WannaCryIV. Are ransomware attacks getting worse?V. The future

The US is coming out of a particularly intense spate of ransomware attacks. Last month, hackers shut down the Colonial oil pipeline, causing gas prices to spike. This week, similar cyber attacks disrupted operations at the meatpacking plants of JBS SA, while the public was made aware of earlier hacks on the transportation authorities in New York City and Martha’s Vineyard. Hackers made at least $18 billion during a crime wave in 2020, according to an estimate from Emsisoft.

To the general public, these attacks may seem like random disruptions to various industries. But to the people launching these attacks, they are anything but random.

I. How it works

What is ransomware?

Ransomware is a type of malicious software that withholds access to a user’s systems or data until the user pays a ransom. It’s often designed to spread throughout a connected network of computers, such as a hospital or company. It can affect organizations, such as governments or companies, as well as individuals.

How does ransomware get on your computer?

Like many types of malware, ransomware can infiltrate a system when users download suspicious materials, follow links, click ads, or visit an unsecure website.

How do you prevent a ransomware attack?

For the average person, it’s important to update your software whenever there is one available. That will often patch vulnerabilities the software’s maker has discovered.

For companies and organizations, here are some suggestions from Harvard Business Review:

- Have (and review) an incident response plan so that, in the event of an attack, it’s clear who is responsible for what actions.

- Make sure your company’s cyber insurance policy covers ransom.

- Turn on multi-factor authentication for all company accounts, including service accounts and social media accounts. Put strong spam filters in place.

- Establish a communication channel on a secure texting app so that senior management can communicate in the event of a cyberattack that takes down company email systems.

- Train and educate employees to identify suspicious emails and links.

- Consider hiring a reputable forensic firm to undertake a “prophylactic threat hunt” to find weaknesses.

- Assess the cybersecurity programs and protocols for your key vendors.

- Test back-up systems regularly and make sure they’re separate from other company systems.

What can happen as the result of a ransomware attack?

According to the Berkeley Information Security Office, a ransomware attack can result in:

- Temporary or permanent loss of sensitive or proprietary information,

- Disruption to regular operations,

- Financial losses incurred to restore systems and files, and

- Potential harm to an organization’s reputation.

Who are the hackers, and what do they want?

Ransomware hackers can be criminal groups or those with ties to nation-states. Most just want money: 86% of such attacks are financially motivated. DarkSide, the group that hacked the Colonial oil pipeline in May, took the unusual step of posting a statement on its website stating that it didn’t mean to cause chaos, it just wanted cash. Others, however, are after sensitive data that they can then sell on the black market, or actually are out to cause chaos.

How much do hackers ask for in ransom?

For individuals, the ransom is often a few hundred or thousand dollars, or sometimes cryptocurrency like bitcoin. For companies and governments, it’s often in the millions of dollars. That’s a big price tag—but not paying the ransom and rebuilding IT systems can sometimes cost much more.

Should victims pay the ransom?

The US government suggests that people and organizations subject to ransomware attacks not pay the ransom. It emboldens other would-be hackers, and the victims might not get their data back anyway. The person who pays could also be fined by the government (pdf) for paying a “sanctioned” person or group.

It’s easy to say in the abstract that companies shouldn’t pay ransoms, but for any individual organization, that’s a hard choice. Often, it’s much cheaper to pay off a hacker than it is to recreate your company’s IT infrastructure from scratch. And as hackers have become more professional, more victims have been willing to pay in order to get operations back online.

II. The targets

These are just a few of the victims of notable hacks in the past few years. They were subject to ransomware and other kinds of digital attacks.

Major hacks in the US

- Federal

- A 2015 breach of two federal agencies, likely by Chinese hackers, gave the hackers access to sensitive information on 21 million Americans.

- In 2016, Russian hackers infiltrated servers at the Democratic National Committee.

- In 2020, Russian agents hacked nine US government agencies.

- The group behind the 2020 SolarWinds attack was reportedly at it again in May 2021. The group, called Nobelium, “target[ed] government agencies, think tanks, consultants, and non-governmental organizations,” according to Microsoft.

- Local

- Atlanta was hacked in 2018. It refused to pay the ransom and ended up having to spend $17 million reconstructing its IT system.

- Baltimore’s 2019 hack ended up costing $18 million to get the city’s computer network back online.

- A 2019 ransomware attack affected 22 towns in Texas.

Infrastructure hacking incidents

- Power companies. The 2017 ransomware Petya affected power companies in the Ukraine, as well as entities in Denmark, Russia, India, Spain, France, and the UK.

- Transportation systems. New York City’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority and the Martha’s Vineyard ferry system were both subject to ransomware attacks in 2021.

- Healthcare systems. In 2017, BitPaymer ransomed the UK’s National Health Service for US$200,000. In 2019, New Jersey’s largest hospital network paid $670,000 to regain access to its digital systems.

- Schools. In March 2021, remote classes in public schools in Buffalo, New York were shut down due to a ransomware attack.

- Libraries. People couldn’t borrow or return books in St. Louis in 2017 after a ransomware attack shut down computers at the library’s 16 branches.

- Financial institutions. In 2019, hackers stole $7 million in cryptocurrency from Singapore-based exchange DragonEx.

- Police departments. An Illinois police department paid the ransom that shut down their computers in 2017, but did not disclose how much.

Company hacking incidents

- Banking, financial services, and insurance (BFSI) were the industry most targeted by cyberattacks in 2020, facing 60% of the total threats globally. Manufacturing and pharma companies have also become popular targets.

- In 2017, global shipping company Maersk was hacked by a cyberweapon called NotPetya, shutting down operations. Though the hack did come with a ransom message, Wired notes, “NotPetya’s ransom messages were only a ruse: The malware’s goal was purely destructive.”

- An Iranian hacker stole scripts, celebrity contact information, and unreleased episodes of Game of Thrones by infiltrating HBO’s network in 2017.

- Sony was hacked and its emails and other information released in 2014 because of its film The Interview, about the assassination of Kim Jong Un.

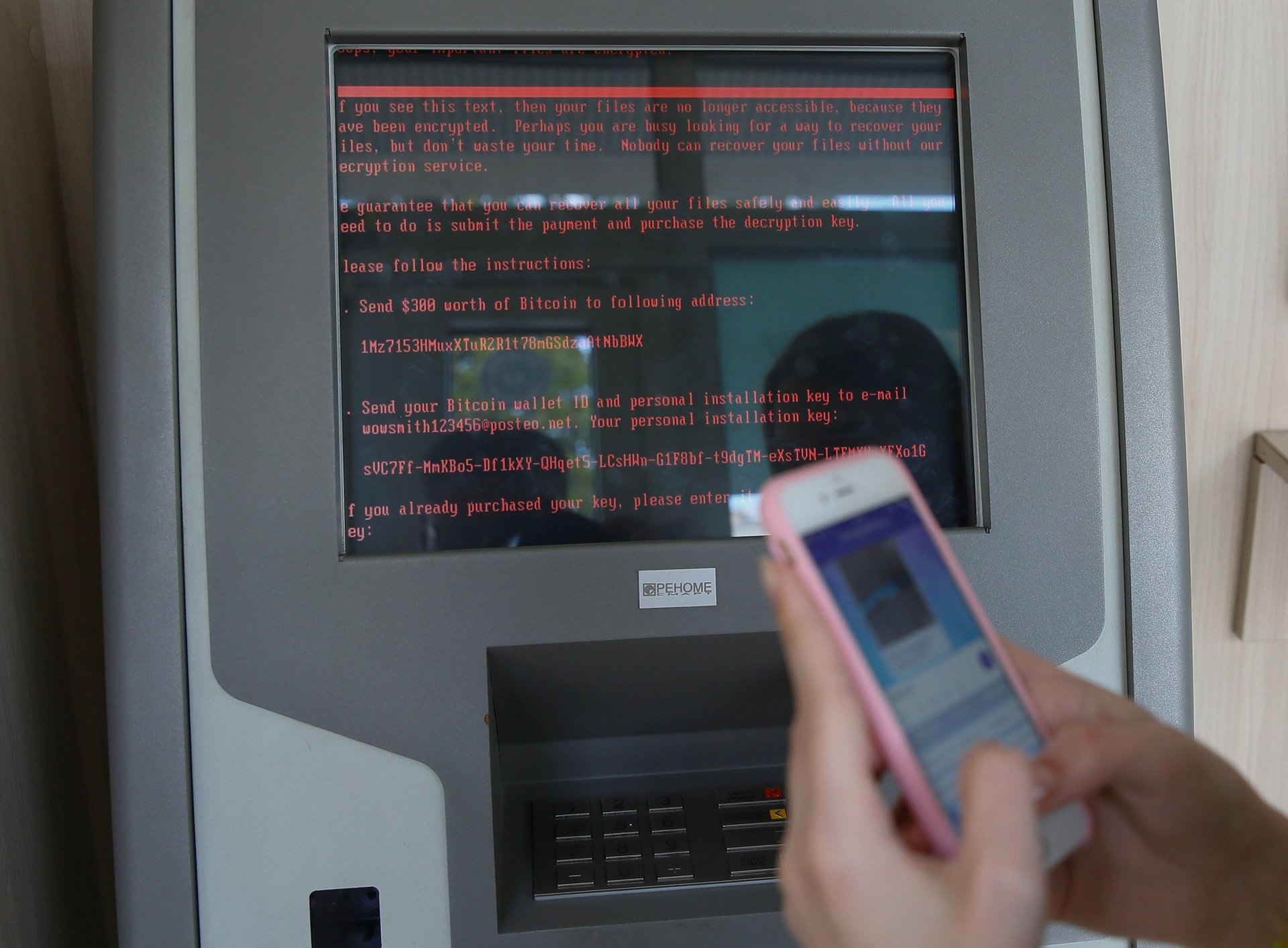

III. Case study: WannaCry

In 2017, the world got a sense of how global—and destructive—a ransomware attack can truly be.

The ransomware, called WannaCry, was a worm—it started from a single computer and spread to others. “It attempts to exploit vulnerabilities in the Windows SMBv1 server to remotely compromise systems, encrypt files, and spread to other hosts,” read a report (pdf) from the National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center. The malware was based on EternalBlue, a hacking tool created by, and then leaked from, the US National Security Agency (NSA).

Affected users would open their computers only to find that their files were encrypted, along with a message asking them to pay between $300 and $600 for the keys to get them back. The group behind it called itself the Shadow Brokers and was later found to be linked to the North Korean government.

The effect was profound for its scope and severity. WannaCry spread across 74 countries to an estimated 45,000 systems. In the UK, 16 NHS organizations were affected, locking doctors out of patient records and reportedly forcing emergency rooms to send patients to other hospitals. The hack also impacted governments, railways, and private companies.

In just two weeks, the hackers made about $140,000 in bitcoin. Microsoft released patches to fix the vulnerability, but users were slow to update their software. Networks continued to be hit through at least 2018. Earlier this year, the US Department of Justice formally charged three North Koreans for the WannaCry hack, along with several others, but none have faced legal consequences, as North Korea does not extradite its citizens to the US.

IV. Are ransomware attacks getting worse?

Ransomware attacks aren’t new—they’ve been around since at least the early 2000s. But they are getting worse. Here’s what “worse” means:

- More frequent attacks. Between 2018 and 2019, the number of ransomware cases reported to the FBI increased by 37% (pdf), according to a report by the US Treasury. Things have only deteriorated since then: The number of attacks grew 150% between 2019 and 2020. “By any measure, 2020 was the worst year ever when it comes to ransomware and related extortion events,” acting deputy attorney general John Carlin told the Wall Street Journal.

- Higher ransoms. Yes, ransoms are getting higher, according to the US Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency, which on its website notes: “The monetary value of ransom demands has increased, with some demands exceeding $1 million.”

- More targeted attacks. Most hacks can be broken down into one of two categories: opportunistic or targeted attacks. In opportunistic attacks, hackers send malware to any number of systems, hoping that some will have inadequate digital security to allow the malware to infect it. Targeted attacks, however, are much more surgical in choosing their victims—usually bigger companies or critical infrastructure. According to the blog Cyberark, “These attackers are very creative, often going to great lengths to understand a victim’s technology stack so they can identify and exploit vulnerabilities, while pinpointing the most valuable data to encrypt and hold for ransom.” This process, which some hackers call “big game hunting,” can take months.

- More sophisticated methods. The methods hackers use to introduce malware have continued to evolve with the security methods to block them. But hackers’ threats have also gotten more sophisticated. Some warn that they will publish stolen data or elicit fines from regulators if the intended victim doesn’t pay up.

V. The future

Experts consider ransomware to be a rising threat. As MIT Tech Review notes, this is at least in part due to years of inaction from the federal government, which didn’t make it a particularly high priority among its overall cybercrime response.

That now looks like it may change. In April, the US Department of Justice created a task force to deal with ransomware attacks “to make the popular extortion schemes less lucrative by targeting the entire digital ecosystem that supports them,” according to WSJ. In response to the Colonial Pipeline hack, the Biden administration has upped the ante. It created a specialized process to address the attacks and considers hackers to be a national security threat on the same priority level as terrorism, according to Reuters.

It’s unlikely that ransomware attacks will ever completely go away. As the world is increasingly digitally connected, hackers will find new targets and new ways to evade security protections. But they may become less popular, either because a new hacking method has proven to be more effective, or because the consequences for committing these crimes are too severe to be ignored.