BlackRock’s Larry Fink is calling BS on Big Oil’s climate strategy

Big Oil and gas companies are under unprecedented pressure from shareholders, courts, regulators, and the public to cut their carbon emissions to help avert climate change. Many are choosing to hone their business in on the most efficient, high-yielding assets—rigs, drilling rights, refineries, pipelines, and the like—and sell off whatever’s particularly carbon-intense.

Big Oil and gas companies are under unprecedented pressure from shareholders, courts, regulators, and the public to cut their carbon emissions to help avert climate change. Many are choosing to hone their business in on the most efficient, high-yielding assets—rigs, drilling rights, refineries, pipelines, and the like—and sell off whatever’s particularly carbon-intense.

According to the energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie, a global firesale of at least $140 billion in oil and gas assets is ongoing. It’s driven by emissions concerns, long-term uncertainty about oil demand in a decarbonizing world, and a desire by many oil companies to pay off debt and raise cash for dividend payments and other shareholder benefits. Shell, for example, sold off nearly $1 billion in assets in Egypt in March and is reportedly considering the sale of up to $10 billion in assets in Texas.

That strategy is great for making an oil company’s balance sheet appear greener. But those assets don’t stop emitting when they trade hands from one owner to another, and a growing number of energy economists are concerned that they may instead become even harder to quash.

The problem with Big Oil’s divestment spree

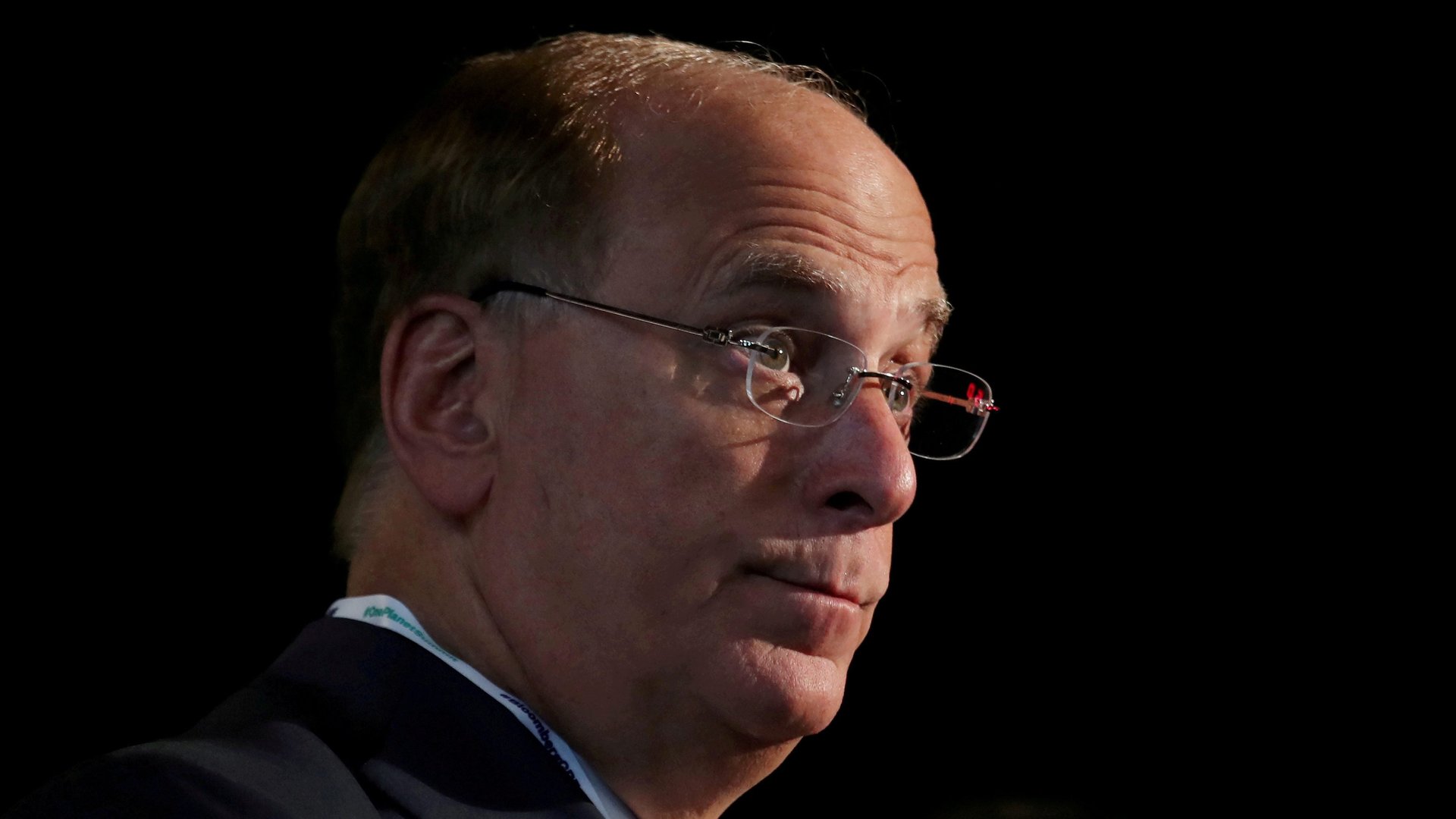

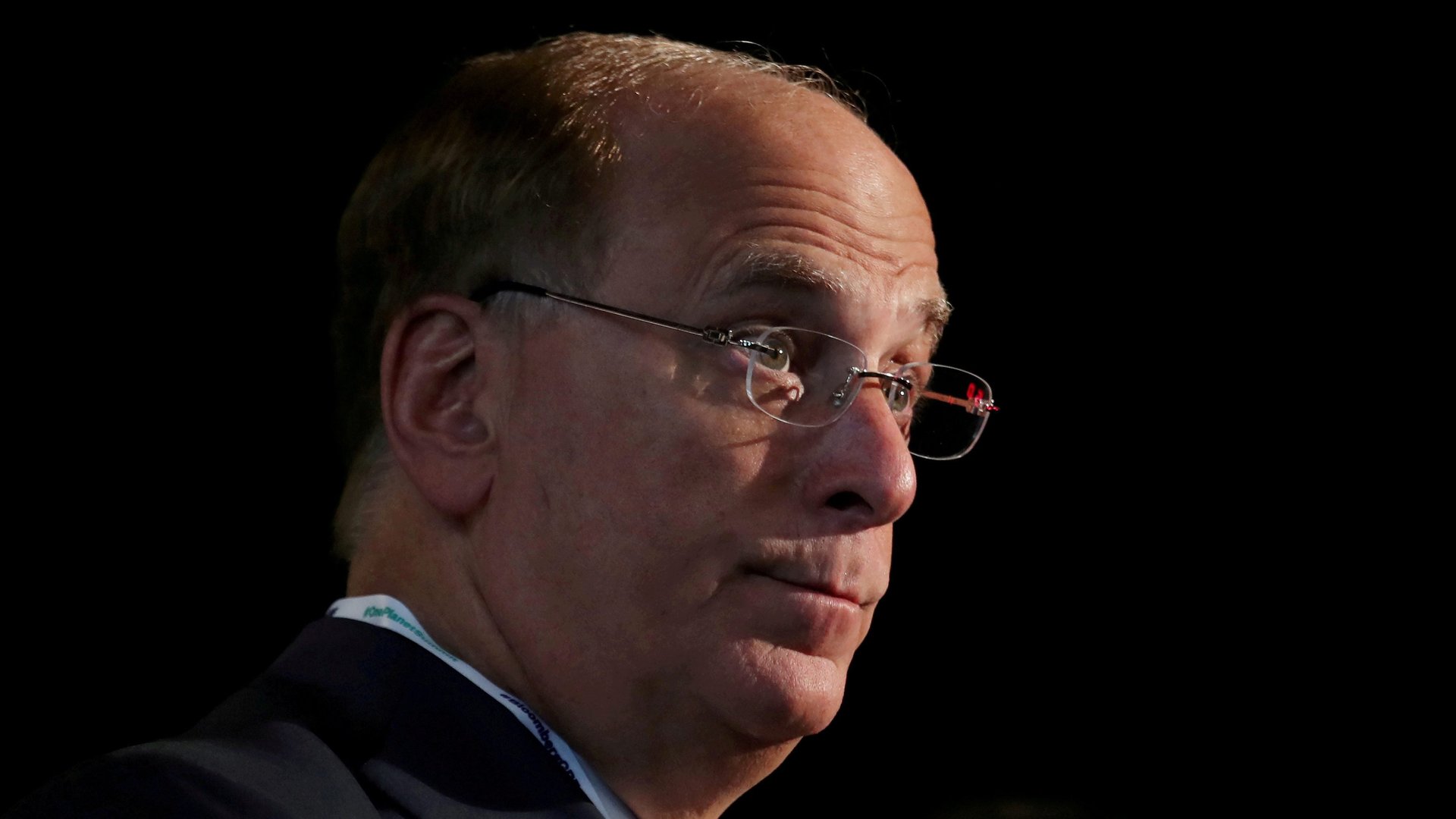

Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, is the latest to sound the alarm. Speaking to a gathering of G20 finance ministers in Venice on July 11, Fink cautioned that “divesting, whether done independently or mandated by a court, might move an individual company closer to net zero, but it does nothing to move the world closer to net zero.”

These assets are primarily purchased by either smaller private oil companies or state-owned enterprises like Saudi Aramco. Both groups face no obligation to disclose anything about their operations, forcing those emissions into the shadows. Small companies have less willingness and cash to keep up with the latest emissions-control hardware, and a far worse track record than majors on spills. State-owned companies, meanwhile, are typically willing to continue production even when the price of oil is low, meaning assets they own are more likely to be used long into the future.

Oil demand is still too high

Fink doesn’t place all the blame on Big Oil, though. Ultimately, he said, a bigger problem is that oil demand isn’t falling fast enough (not counting the pandemic dip). If policymakers and the public succeed in nudging Big Oil to divest without doing more to electrify the transportation sector and eliminate other sources of oil demand, Fink said, the effect will be to push the price of oil to $100 or more per barrel—which “will only sow greater economic inequality” and drive emissions even higher.