There’s still only one way for authoritarians to control the internet

The Cuban government briefly shut off the entire country’s internet on July 11 in an effort to disrupt historic nationwide protests that were being coordinated and live-streamed using the island’s nascent mobile data network.

The Cuban government briefly shut off the entire country’s internet on July 11 in an effort to disrupt historic nationwide protests that were being coordinated and live-streamed using the island’s nascent mobile data network.

Internet shutdowns are a well-worn tactic by authoritarian regimes over the past decade. After Egypt blocked the web during Arab Spring protests, embattled dictators have repeated the tactic in Syria, Myanmar, Uganda, Eswatini, and most recently, Cuba. Full shutdowns, however, represent a worst-case scenario for any regime: In addition to disrupting protesters, they also disrupt the economy and make it harder for the government itself to operate. They are a censorship method of last resort.

The fact that dictators still find themselves downing the entire national internet a decade after the Arab Spring shows just how much they’ve struggled to censor the web in more targeted ways, according to Doug Madory, director of internet analysis at the network observation company Kentik. “People are so wiley, and there are so many good tools to evade censorship now, that you’re back to square one,” he said. “The only option if you really want to shut off [specific websites or apps] is you’ve got to shut everything off.”

In moments of crisis, authoritarian regimes have had to admit that they can’t fully control the web. For that reason, the blackouts offer a source of optimism: They show how devilishly hard it still is for a dictator to censor the internet. People living under oppressive regimes have kept just ahead of censors, and a slew of free digital tools designed to evade firewalls will keep things difficult for dictators for the foreseeable future.

How dissidents evade web censorship

The single greatest tool for evading internet censorship is a virtual private network (VPN), which helps web users disguise where in the world they’re browsing the web and what content they’re accessing.

An authoritarian regime can block traffic to specific websites or apps easily enough. The Cuban government has spent the past several days cutting off all web traffic between the island and the servers that run encrypted messaging apps like Signal, Telegram, and WhatsApp.

But VPNs have allowed Cubans to access those apps indirectly: Instead of trying to connect with WhatsApp’s servers directly, a Cuban protester using a VPN could connect with a server somewhere in Norway, for example, which would then connect with WhatsApp’s server and act as a proxy, sending information back and forth between WhatsApp and the user.

Because there are so many VPNs, and because those VPNs use so many different proxy servers around the world to mask web traffic, it’s virtually impossible for any government to block every VPN all the time. Even in China, which has invested steeply in its online censorship operation, it’s still possible (although difficult) to use a VPN to evade the country’s Great Firewall.

“People are getting more savvy about how to evade these types of censorship,” said Madory. “Ten years ago it wasn’t that common that people would have a VPN on their phone, but in a lot of these places, like Iran, where people are used to a lot of internet censorship, it’s become quite normal. People know what VPNs are and they use them quite a bit.”

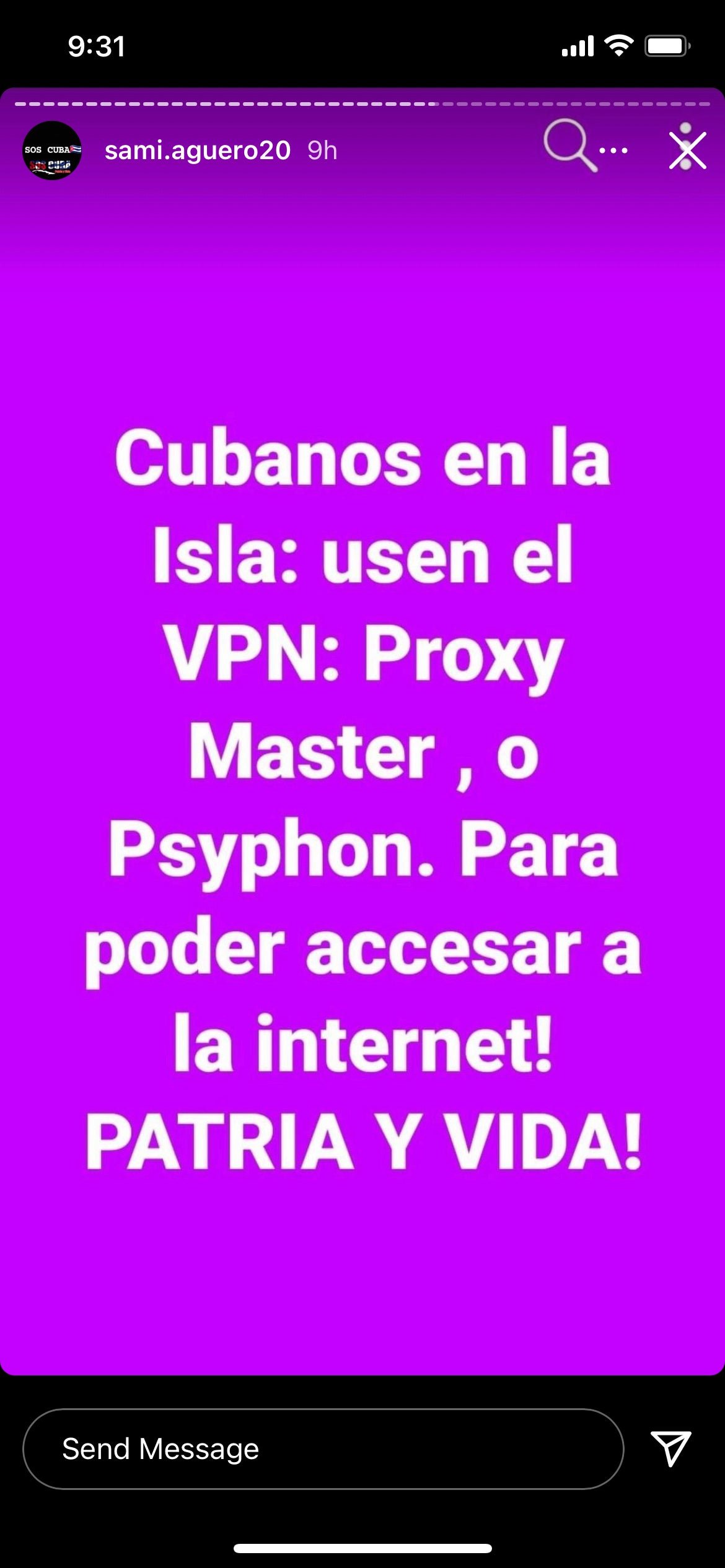

In response to censorship, Cuban web users have begun to spread the word about VPN smartphone apps like Psyphon, Proxy Master, and Ex-pressVPN.

On July 11, as protests erupted across Cuba and videos and images of the demonstrations gushed onto social media platforms, the Cuban government faced the most visible challenge to its power in its 62-year history. The regime turned in desperation to the nuclear option: a full, national internet shutdown.

How Cuba turned off the internet

Shutting off the web is relatively simple in Cuba. There is only one undersea cable connecting the island to the rest of the web-browsing world, and all traffic that travels across that cable is controlled by the state-run telecom operator ETECSA. The government also owns all the ground stations capable of communicating with satellites that can beam internet down from space (which puts a damper on any plans for Elon Musk to fly a satellite over Cuba and deliver uncensored internet to all).

With that level of monolithic control over the infrastructure that runs the internet, Cuban authorities can simply cut power to the network, or write a few lines of code that instruct it not to let any traffic in or out. They blocked all internet traffic for the country for about half an hour on July 11, and have since appeared to block the web in certain restive areas, in addition to throttling the speed of web traffic and attempting to block certain apps and sites.

But the Cuban regime, like many authoritarian regimes before it, seems to be finally coming to terms with the full threat of an internet-connected population that is learning to use the digital tools at its disposal to evade censorship. The government is now grasping for ways to control the network it hoped would help grow the Cuban economy without expanding opportunities for dissent.

Last month, Cuban journalist Yoani Sánchez quoted a telling line from a 2020 communist party summit in Havana, delivered in a keynote address by outgoing dictator Raúl Castro. “We have talked about the benefits and dangers of using the Internet and social networks for dozens of years,” Castro said. “There is no place for naivety at this stage or unbridled enthusiasm for new technologies, without first ensuring information technology security.”