College athletes have long been influencers. Now they’re getting paid like them.

When America’s college athletes could begin profiting off their personal brand for the first time this summer, Lauren Burke was ready.

When America’s college athletes could begin profiting off their personal brand for the first time this summer, Lauren Burke was ready.

The 22-year-old rising senior on the University of Texas softball team had made a name for herself on the field and off. During the pandemic year’s shortened 2020 softball season, Burke racked up a monstrous .453 batting average, ranking second in the Big 12 conference.

But it’s likely that most of her fans know her from TikTok. Burke, who mainly posts about softball and fitness, has 400,000 followers on TikTok and nearly 100,000 on Instagram. Burke’s first-ever video — of her and a teammate at batting practice — garnered 1.2 million views. Those are follower counts to which many full-time content creators aspire.

But until recently, college athletes could not monetize their social media presences like typical influencers. The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) has historically limited its athletes’ ability to make any money at all — even side businesses unrelated to their athletic pursuits. After a series of court rulings against it, including a unanimous one by the Supreme Court, the NCAA changed its rules on July 1, allowing collegiate athletes to monetize their fame, known in the business as names, images, and likenesses (NIL), for the first time.

“Student-athletes are going to be some of the best influencers and content creators out there because of the assistance we have within the university, [and] the fans and supporters that we have too,” Burke said. “They’re gonna be really good at what they do.”

College athletes have long been social media influencers, and now they can get paid like them too. Expect some to get paid better than the pros.

A long time coming

The NCAA, the organization in charge of college sports in the US, was under mounting pressure ahead of the NIL rule change. The decision marks a major concession in a drawn-out debate about the amateur nature of US college sports, a multibillion-dollar industry that has, until now, denied athletes the opportunity to make money beyond their scholarships—whether they are obscure benchwarmers or household names.

In the last decade, the dissonance between college athletes and the universities that profit off of their success had become increasingly apparent. College coaches are the highest-paid public employees in most states, earning $9.3 million in the case of Clemson football coach Dabo Swinney, by far the highest-paid in South Carolina. Yet numerous reports have found that some college athletes — even some star players — have even gone hungry or homeless while playing. Since then, unionization efforts at a few schools — starting with Northwestern University’s football team — have attempted to gain rights for student-athletes but have come up short because the National Labor Relations Board deemed college sports outside of its purview.

NIL revenue “always represented a third way for the NCAA,” said Galen Clavio, an associate professor and director of the National Sports Journalism Center at Indiana University. “The [NCAA] could start to allow athletes some degree of compensation without having to go through the likely legal hassle of directly paying athletes.”

The recent decision came in the waning days of June—before 14 state laws went into effect on or around July 1 that allowed athletes to profit off their NIL whether the NCAA liked it or not. A dozen more are already signed into law and will take effect in the coming years. And many other states, as well as Congress, have introduced NIL legislation for college athletes. Many supported the state bills solely so their public universities wouldn’t lose a competitive advantage in recruiting.

On June 21, 2021, the US Supreme Court also affirmed a district court decision that the NCAA violated antitrust rules by limiting education-related benefits schools can provide to students, a unanimous decision that could lead to further rulings on the side of college athletes. Ultimately, the NCAA rules change was a belated attempt to level the playing field once the decision was largely out of the organization’s hands.

The NCAA still does not allow colleges and universities to pay athletes like professional sports leagues pay their players—with salaries and benefits—but the new changes will allow college athletes to solicit endorsement deals, sell their own merchandise, and make money off of their social media accounts.

Student-athletes are getting paid

In early hours and days after the rules changed, a flurry of college athletes posted about brand deals and other business ventures. They range widely in style, pay, and renown: Fresno State women’s basketball players Hanna and Haley Cavinder signed with Boost Mobile, Alabama defensive end Ga’Quincy “Kool-Aid” McKinstry is selling a non-fungible token (NFT) through SkyBox Sports, and Iowa men’s basketball player Jordan Bohannon is signing autographs through a partnership with a local fireworks store.

“Student-athletes understand these platforms much better than a lot of the professionals now getting paid to manage them,” said Kenon Brown, an associate professor at the University of Alabama, “and I think it’s coming into the spotlight with these endorsements that you’re seeing.”

Though most athletes are likely looking at much smaller deals with local businesses, top athlete influencers like the Cavinder twins or Louisana State University gymnast Olivia Dunne, who has 4 million followers on TikTok, could command endorsement deals in the millions of dollars from major brands. Last week, Alabama football coach Nick Saban said that sophomore quarterback Bryce Young, the team’s presumptive starter, is already receiving nearly seven-figure offers for NIL deals. “And it’s like, the guy hasn’t even played yet,” Saban said. “But that’s because of our brand.”

Confusing NIL rules

Clavio, who serves on Indiana University’s NIL taskforce, a body advising the school on how it should handle these changes, said the NCAA had an opportunity to set standard rules across the board but deferred that responsibility to the states and individual universities to figure it out for themselves. “The NCAA had a chance to work on an actual solution and instead they punted and now essentially we’re gonna see the market largely create its own realities,” he said. “I think those realities could be vastly different from one school to the next or one state to the next.”

NIL rules vary from state to state and university to university. Some states and institutions, for example, do not allow student-athletes to do NIL campaigns while wearing school uniforms or colors. Burke, for one, said she has to choose between signing up for TikTok’s creator fund — a program that pays top creators per view — or cease wearing her Texas uniform in videos, which she doesn’t want to do right now.

This confusion has begotten new market opportunities for businesses eager to help athletes cash in on their fame, and take a cut of the action.

“There is a whole cottage industry based around the name, image, likeness marketplace and compliance education and supplemental services that are selling to schools and athletes and brands,” said Matt Brown, the author of the Extra Points newsletter, which covers off-the-field aspects of college sports. “Some are positioning themselves as experts in a space where it is impossible to be an expert,” because universities are still writing rules and laws are only now going into effect.

“Every single Division I college athlete has a NIL value greater than zero,” he said. “Anyone who tells you that athletes have no value is mistaken. However, it’s going to be a job like anything else and in order for an athlete’s value to be above a few hundred dollars, they’re going to have to put some effort behind it.”

Making a Cameo

Steven Galanis has been thinking about the NIL opportunity for college athletes since he co-founded his company Cameo in 2016. Galanis, now CEO, played hockey for Duke University, while his co-founder Martin Blencowe ran track at the University of Southern California. While around famous athletes at top universities, the pair saw the limits of college stardom.

“A lot of our best friends were these guys that had made so much money for their universities—people were wearing their jerseys, they were selling out stadiums, they were making more people apply to college,” he said. “And they made zero dollars on it.”

That, in part, inspired them to start Cameo, a $1 billion company that lets celebrities and influencers sell personalized shout-out videos to fans. Talent on the platform set their own prices and an appropriate response time. Saints quarterback Drew Brees charges $750 for a video, pop star Paula Abdul charges $449, and TV host Jerry Springer charges $135.

He thought the business model made a lot of sense for college athletes, who he never expected to get paid like pro athletes. “It was very clear that schools were never going to pay, so direct-to-fan monetization was the only way this was going to work,” he says. To do this, Cameo partnered with INFLCR and Teamworks, two NIL-focused software companies, at the end of 2020.

Sports are now central to Cameo. The company has quickly added college athletes to its legions of talent. More than 280 college athletes are fully onboarded with 200 more in the pipeline, Cameo said, adding that they have completed more than 1,500 videos for fans so far. Kentucky basketball’s Davion Mintz, Alabama softball’s Montana Fouts, Notre Dame football’s Kyle Hamilton, and Oklahoma gymnastics’ Ragan Smith are among the most popular early entrants. Cameo has also been pushing its Cameo for Business solution, a way to connect talent with small and medium-sized businesses for commercial opportunities.

Galanis said his pitch to college athletes, pro athletes, and nonathletes is the same. “You’re getting paid to be more famous,” he said. “That person [receiving the video] becomes a bigger fan than they ever were before.”

College athletes are ready

Burke has been preparing for the moment when she can make money off her NIL with the help of the University of Texas. The school has trained students for the NIL changes during the pandemic through its Leverage program, a series of classes aimed at helping students with personal branding, entrepreneurship, financial literacy, and, in the early days of NIL, compliance.

Brown, the University of Alabama professor, said that schools that help their students take advantage of their new earning power will be the biggest beneficiaries. Schools’ policies and attitudes toward NIL could factor into recruiting, after all. “Obviously, they can’t cut deals for them, but they can give athletes the tools necessary to take full advantage of these new opportunities,” he said. “The schools that succeed will be the ones that empower their student-athletes, not hinder them.”

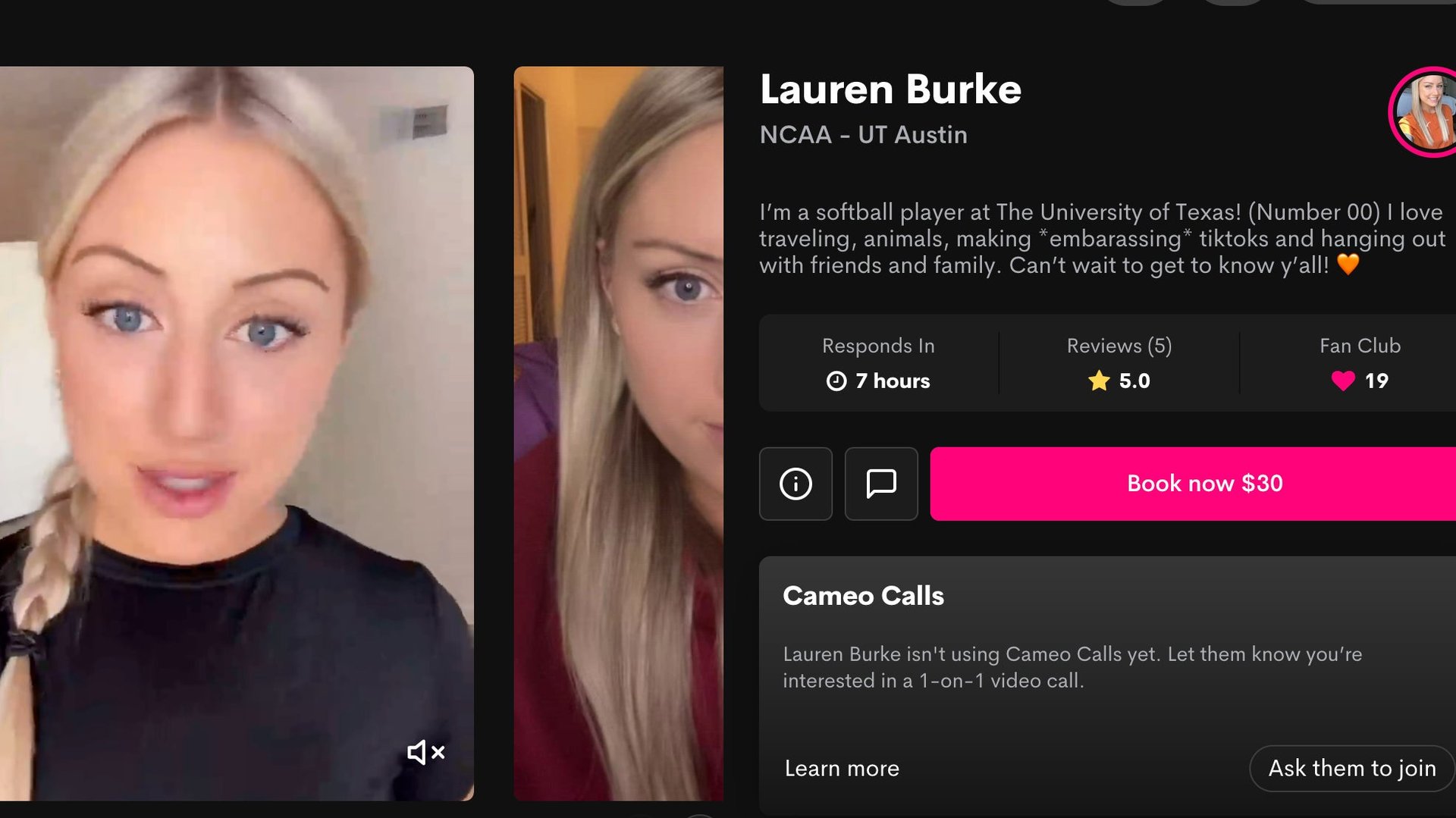

Burke, who took advantage of the university’s Leverage program, has already signed up with talent agency JS1, joined the athlete marketing platform OpenDorse, and inked a few brand deals most of which aren’t yet public. On Cameo, she’s charging $30 a pop for shout-out videos for fans and has already done one Instagram Stories campaign for the beauty retailer Vanity Planet for an undisclosed sum.

In our interview two weeks ago, Burke said these new rules are “completely life-changing” for many female athletes, especially ones without lucrative professional opportunities in their sport after college. “When people are hesitant about us making money, it’s difficult for me to understand that because I don’t have the opportunity to sign a multimillion-dollar contract post-college,” says Burke. “I don’t have that. I wish I did, but I don’t have that opportunity.”

Despite the growth of women’s sports in the US, which saw TV ratings soar during the pandemic, sports like softball do not offer much in the way of professional opportunities. Even start softball players like Jennie Finch and fellow Texas Longhorn Cat Osterman, household names due to their Olympic success, have limited options to go pro. The average salary in America’s premier professional softball league, National Pro Fastpitch, is reportedly $5,000, and the number of active teams in the league sometimes fluctuates from year to year.

But for Burke, the new rules mean a new kind of freedom. “It’s our name, it’s our image, and it’s our likeness,” she said. “We should be able to capitalize on it, profit off it, and represent whatever brands that we choose.”