To jumpstart your favorite cause, help early and then let the crowd take over

When it comes to turning a new idea into a success, the first drops of support—in the form of money, praise, or publicity—are the most important. And the faster they come, the better the idea will be at attracting more.

When it comes to turning a new idea into a success, the first drops of support—in the form of money, praise, or publicity—are the most important. And the faster they come, the better the idea will be at attracting more.

A new study shows how early public support, of a business, an individual, or even an idea, substantially boosts its appeal.

The research attempted to get to the bottom of a longstanding debate in sociology: whether success comes from people’s inherent abilities, or from some outside advantage: money, friends, race, or, in this case, the proverbial bandwagon.

Sociologists at Stony Brook University in New York set up a series of experiments to see whether they could trigger the public into supporting a project, or person online. ”People tend to give resources to people who already have them,” co-author Arnout van de Rijt told Quartz. “What we really wanted to do is to see how pervasive this tendency was, of ‘success breeds success.'”

To test it, van de Rijt and his colleagues put together a clever, but complicated, experiment.

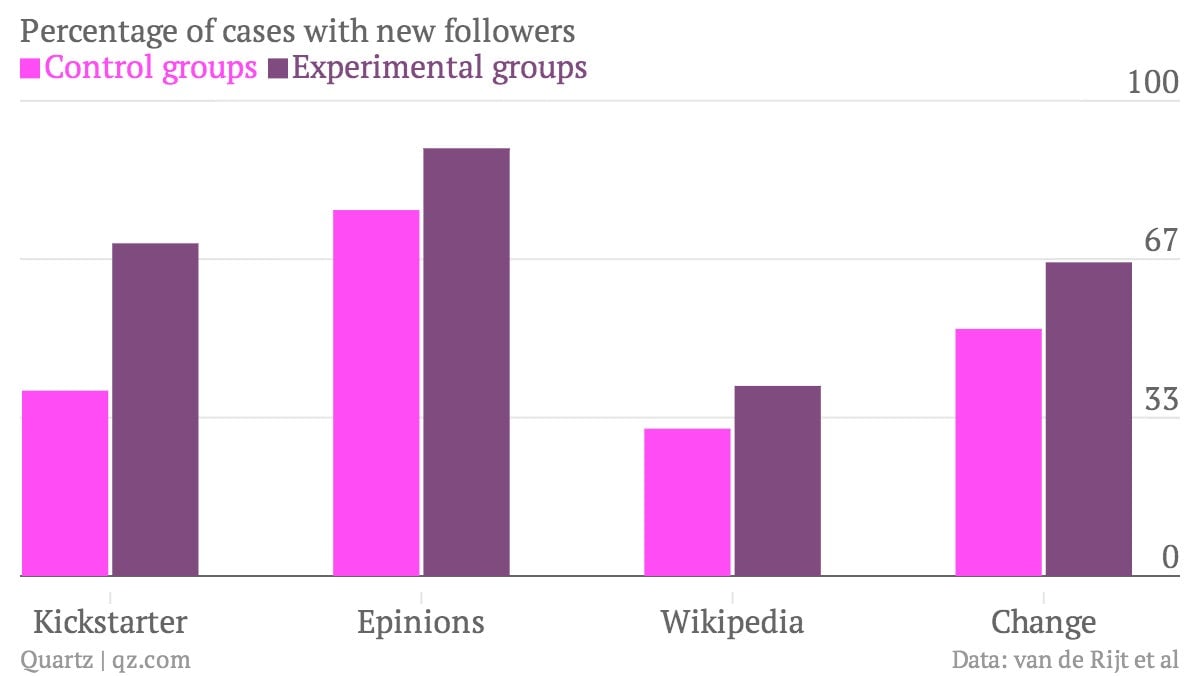

The team used the web as a laboratory for the ways people embrace and support new ideas, an imperfect comparison for real life, they admit, but one that is measurable. The team split their study of success into four different avenues: a sound business idea (Kickstarter.com), a source of knowledge (Epinions.com), good social standing (Wikipedia.org), and an idea deserving support (Change.org).

Then they rounded up their sample groups: nearly 300 Kickstarter campaigns with similar goals and timelines, close to 500 new Epinions reviews that the researchers judged as high quality, about 520 Wikipedia editors with similar rates of edit productivity, and 200 Change.org petitions that were still young enough to have fewer than 15 signatures.

Van de Rijt and his three co-authors randomly split the samples from each web service into two groups: Those who would receive the research team’s grant money, votes, and awards, and those who got nothing. They donated anywhere from 1% to 10% of a Kickstarter projects’ goal, handed out five-star ratings to chosen reviews reviews, gave productivity awards, and added 12 signatures to each petition they’d randomly selected for support. And then they watched.

All this support caused “people to jump on the bandwagon,” van de Rijt said. The Epinions, Wikipedia, and Change.org trials, which saw modest, but statistically significant favor towards the experimental groups.

The Kickstarter experiment was even more successful. Projects they supported were almost twice as likely to get supporters as those in the control.

In a followup experiment, the team tested how much impact shows of support beyond the first had on attracting more followers. By tracking Kickstarter donations that followed theirs, their results showed them that the subsequent donations had a diminishing effect on attracting support.

What this implies, says van de Rijt, is that you should diversify if you want to have the biggest impact. For example, if you want to encourage people to support a certain cause, you should find several charities that do similar work and make modest contributions to them all. (To trigger the effect, other potential donors need to see that you’ve made that first donation.)

“It’s really the first success that matters the most,” says van de Rijt.

Philanthropists, venture capitalists, and angel donors, could take lessons from his research, van de Rijt said, particularly because it encourages them to “do much more good by splitting up your money into smaller pieces rather than lump it together in one location.”