China is hiding how bad income inequality is in the country

Last year, China released estimates of income inequality in the country after concealing the figure for years. Somewhat surprisingly, it wasn’t so bad—and was even a tad better than America’s, a country to which China often draws comparisons in terms of the costs of economic development and nation building.

Last year, China released estimates of income inequality in the country after concealing the figure for years. Somewhat surprisingly, it wasn’t so bad—and was even a tad better than America’s, a country to which China often draws comparisons in terms of the costs of economic development and nation building.

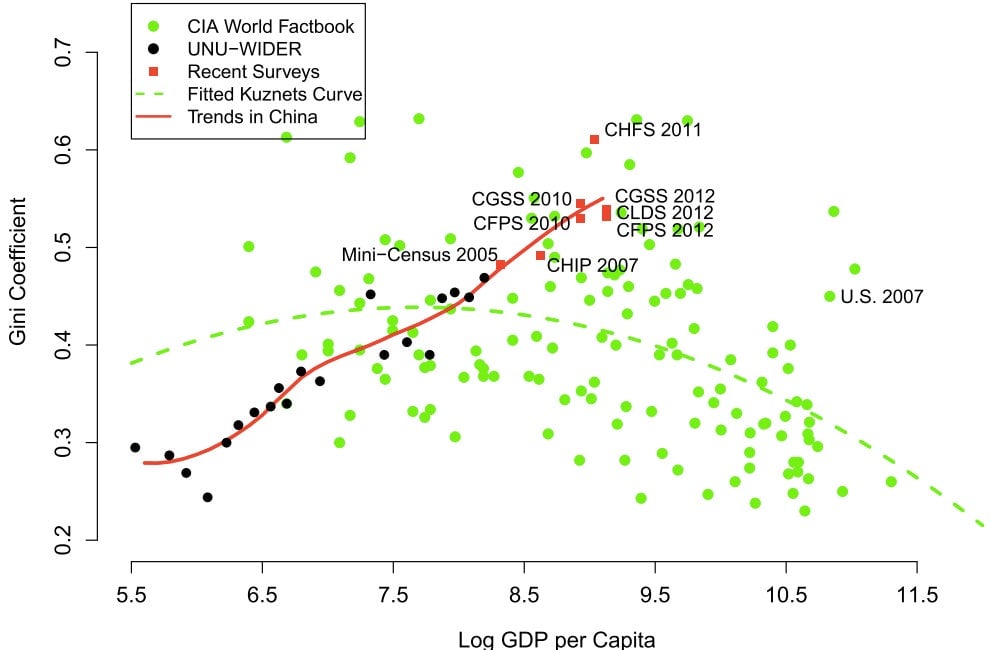

Turns out the gap between wealthy and poor Chinese may be much larger than the government has said and also a good bit wider than that of the US. According to a new study from the University of Michigan, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States (NAS), China’s Gini coefficient is now around 0.55. That’s higher than the official released number last year of 0.474 and higher than America’s most recently released number of 0.477. (The coefficient, a common measure of income inequality, ranges from 0 to 1, with 0 representing the most equal society.)

According to the NAS study, which examines data from a survey conducted across 25 provinces by Peking University’s Institute of Social Sciences, inequality in the country is high in the context of China’s own history as well as in comparison with other countries at similar stages of economic development. As recently as 1980, China’s Gini coefficient was 0.3 (though even that figure was high compared to other socialist states at the time).

Economists and development experts say that inequality typically increases during a developing country’s initial phase of growth and then declines. But in China, inequality has continued to grow even after the economy passed the point of development when the wealth gap usually starts to narrow. In 2002, GDP per capita reached $2,866, but the Gini coefficient remained high at 0.45:

Beijing stopped reporting the figure after it reached 0.41 in 2000, the point at which some researchers have argued it is likely to contribute to social unrest. And the official data finally released last year doesn’t show the indicator going beyond 0.5, the point when income inequality is considered very severe. (China only began releasing the numbers again after researchers estimated it could have reached as high as 0.61 in 2010.)

Holding back data may have been in the government’s interest, an attempt to avoid drawing attention to a reality that an increasing number of Chinese find frustrating. According to the study, a majority of respondents to a survey in 2012 ranked inequality above corruption and unemployment as China’s top problems.

The other reason why officials might want to hold back these numbers is that income inequality is, according to the study, the result of government policies. “The rapid rise in income inequality can be partly attributed to long-standing government development policies that effectively favor urban residents over rural residents and favor coastal, more developed regions over inland, less developed regions,” the authors wrote.