The US child tax credit is making a dent in hunger

After the first payments of the US child tax credits were released, there was a drop in the number of families with children reporting they didn’t have enough to eat and trouble paying household expenses, according to a new Census Bureau Household Pulse survey.

After the first payments of the US child tax credits were released, there was a drop in the number of families with children reporting they didn’t have enough to eat and trouble paying household expenses, according to a new Census Bureau Household Pulse survey.

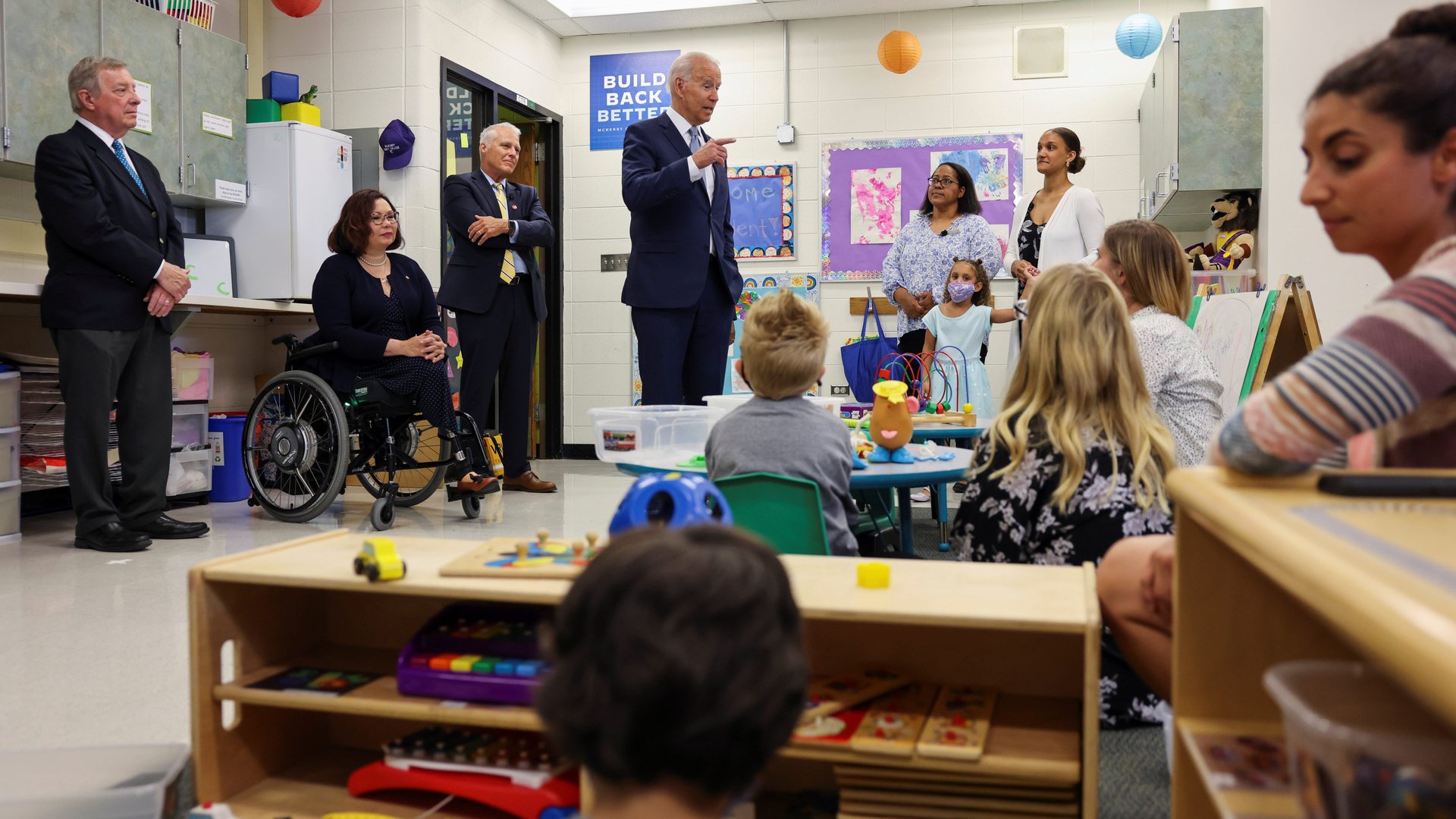

Last month, the Internal Revenue Service began issuing half of the temporarily expanded child tax credits—up to $3,600 annually for children below the age of six and up to $3,000 for those ages six to 16—via monthly payments, to help ease the financial burden on families and to help alleviate poverty. One study found the tax credits could cut the overall child poverty rate by 45%. The IRS will deliver the remaining amount between January and April 2022.

About 35 million eligible families have received the first monthly payment.

Overall, the decline in the share of adults in households without enough to eat was largely driven by families with children that received child tax credit payments. They saw a nearly a three percentage point decline between the surveys conducted before and after the arrival of the first checks. In households without children, and therefore without the additional income, hunger rose.

The decline in the share of adults in households struggling to pay expenses also declined 2.5 percentage points. Those without children saw a slight increase.

The data was collected from July 21 to Aug. 2, and about 6% of the 1.04 million households that were sent surveys responded.

The US child tax credit is being spent on food and childcare

What did respondents spend the cash on? At a time when the price of groceries has been rising, about 47% of respondents spent the payment on food. And 17% of those with at least one child under age five spent their payment on childcare.

Governments in different countries have reported handing out cash can be more effective at reducing poverty than providing services or goods like food or housing. A 2017 study from Stanford University, using data from countries in Latin America, Africa, and Asia, found cash transfers, lead to improved education and health outcomes, as well as reduce poverty. There was also no increase in tobacco and alcohol consumption. The researchers found cash transfers could change what families decide is a serious investment, such as schooling. And when money is given for a specific purpose, people and organizations will use it for that.

The extra economic relief for working families appears to already be working, but given that it is only in effect for a year, lower poverty rates may be short-lived.