Asia’s most popular messaging app is censoring itself in China

Line, a popular messaging app used throughout Asia and beyond, is blocking a list of 535 words for its Chinese users.

Line, a popular messaging app used throughout Asia and beyond, is blocking a list of 535 words for its Chinese users.

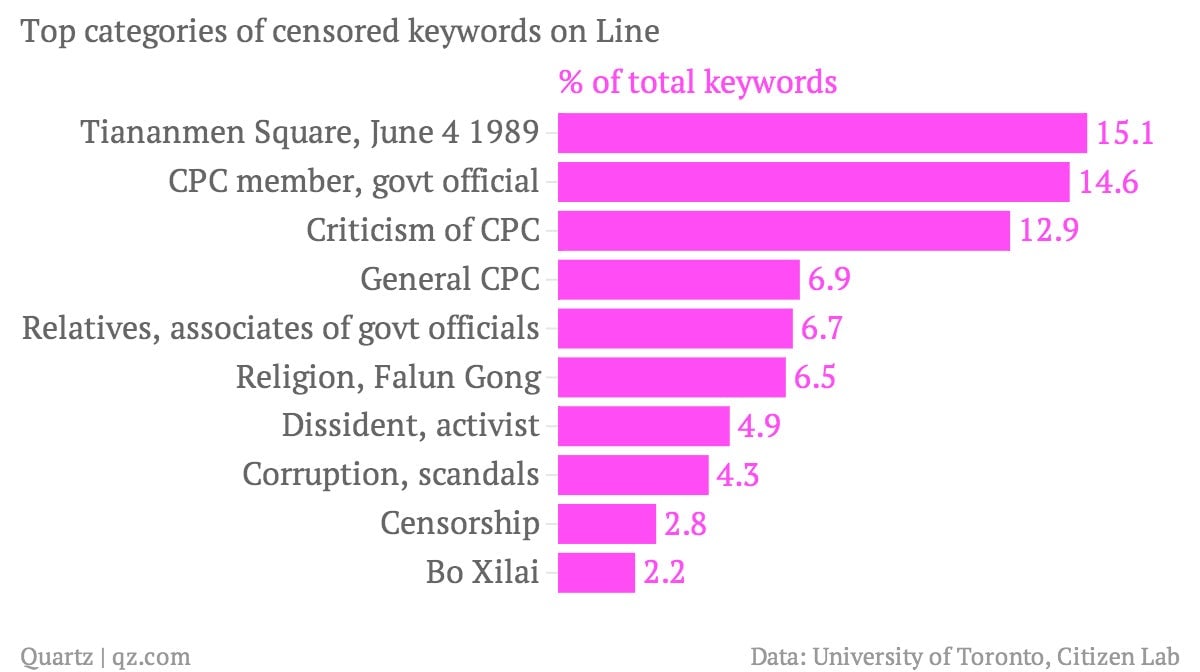

Researchers at the Citizen Lab of the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs reported this week that the Japanese app has added some 300 words to an existing list of sensitive keywords that are banned in China, ranging from the Beijing’s violent crackdown on protests around Tiananmen Square in 1989 to phrases associated with “prurient interests.”

With 400 million registered users, Line is one of the world’s most used chat platforms, second only to WhatsApp and WeChat, its main rival in China. In November, Citizen’s Lab found that the messaging platform had enabled a censoring function for phones registered to Chinese numbers.

In response to the researchers’ latest report, Line said only that it “had to conform to local regulations during its expansion into mainland China.” The company, owned by a Japanese subsidiary of South Korean internet firm NHN, was not immediately available for comment when contacted by Quartz.

But the inclusion of words related to older and low profile scandals suggests the company might not always be following a set of clearly defined regulations, but is also self-censoring on its own accord—a common practice among Chinese media and tech companies.

The list of keywords includes those related ex-Chinese official Bo Xilai, whose scandalous downfall openly discussed on Chinese social media and traditional news media. References to rumors in 2011 that former Chinese leader Jiang Zemin had died are also on Line’s ban list. ”The fact that some of these censored incidents are not high profile seems to indicate that they have been added by Line as a pre-emptive, preventative measure,” the researchers said.

Moreover, there’s little overlap of Line’s blocked terms with those of other popular chatting platforms operating in China, which means that messaging platforms in the country censor not only widely but inconsistently and perhaps arbitrarily.

Only 45 words on Line’s 535-word list matched a similar data set of barred words on Skype in China, which operates with a Chinese partner called TOM. And only 19 of Line’s keywords matched that of Sina UC, a platform owned by the Chinese portal Sina.

Overlap between Sina and Skype was also low—only 138 out of over 4,000 keywords, or 3.2%, were on both lists. According to the researchers, this ”suggests that no common keyword list is provided to companies operating chat programs in the Chinese market.”