Climate change ensures New York City’s first flash-flood emergency won’t be its last

New York City and the surrounding region saw torrential downpours and massive flooding from the remnants of Hurricane Ida on the night of Sept. 1, prompting the National Weather Service (NWS) to issue its first-ever flood flash emergency for the region.

New York City and the surrounding region saw torrential downpours and massive flooding from the remnants of Hurricane Ida on the night of Sept. 1, prompting the National Weather Service (NWS) to issue its first-ever flood flash emergency for the region.

Even as a weakened tropical depression, the storm buffeted has the US East Coast with tornadoes, high winds, and flooding after devastating New Orleans several days earlier. New York and New Jersey saw more than six inches of rain in a few hours. Central Park broke a record set only weeks earlier for the most rainfall in an hour, with 3.15 inches.

The region has never seen anything quite like it. The National Weather Service sent its first flash flood emergency alert for northeastern New Jersey at 8:40pm, and another for all five New York City boroughs roughly an hour later. On Twitter, New York’s NWS branch confirmed that these two instances were the first time it had ever sent a flash flood alert with “emergency” status. Unlike warnings, emergencies indicate an imminent and “severe threat to human life and catastrophic damage” and people should seek shelter immediately. At the same time, tornado warnings were issued for the Bronx and cities in Westchester county, instructing people to seek shelter, often below ground, even as flooding threatened to inundate underground shelters.

Unfortunately, the warnings were accurate. The fast-moving storm left people little time to prepare, leaving many stranded on roads. At least 23 people have died as a result of the storm according to NBC New York, some of whom drowned when water rose in their basements. Streets and subways were inundated under multiple feet of water, leaving drivers stranded on the roads and temporarily halting service on more than a dozen subway lines in three New York City boroughs. As of Sept. 2, more than 84,000 people are without power.

Is climate change fueling storms like Ida?

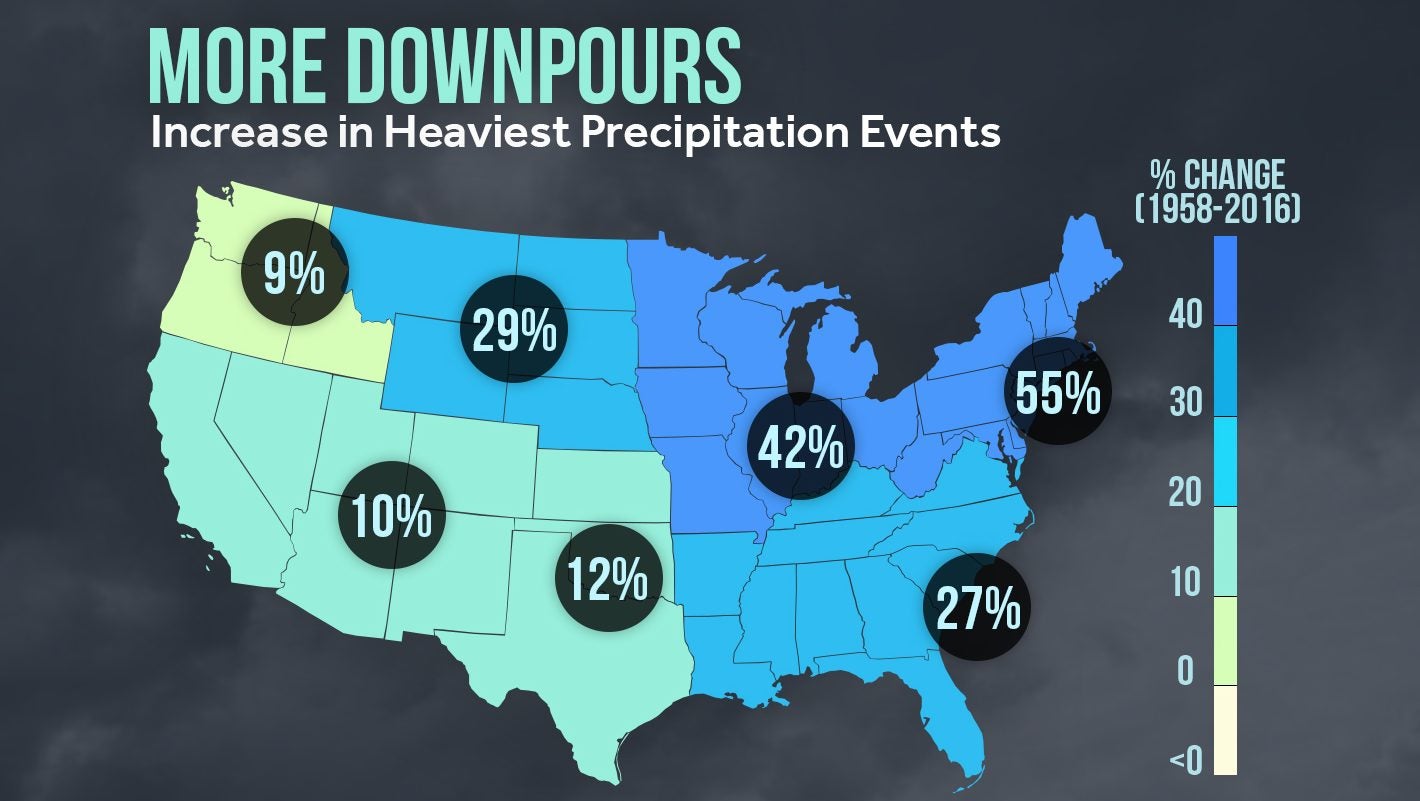

Climate models predict intense storms like Ida will become more frequent. What was once a 100-year storm is now happening once every 30 years, says Climate Central meteorologist Sean Sublette. Weather data already reflects intensifying storms. Between 1958 and 2016, researchers recorded intensifying rainfall across the eastern US, according to the US Global Change Research Program, a federal initiative.

Rising temperatures accelerate evaporation leading to more rainfall and then flooding, says Sublette. Although it will take time to understand exactly how climate change contributed to the most recent storm, climate models are predicting more events like Ida. “In a warming climate, the water cycle is supercharged, so the heaviest rain events are getting heavier,” Sublette wrote by email. “A warmer atmosphere means more evaporation, so more water is available for precipitation.”

The northeastern US has already seen a consistent barrage of storms and flooding this summer. This latest storm comes weeks after Henri, and about two months after tropical storm Elsa caused flash flooding around the city, a pattern scientists have linked to climate change.

Could New York have prepared for this storm?

In May of 2021, New York City government released its first-ever stormwater resiliency plan, acknowledging the continued impact that that these floods will continue to have throughout the city. Most of the plan involves long-term policies such as improved emergency response procedures and infrastructure investments to mitigate flood risk.

But that will have a limited impact on the immediate future. Multiple storms are overwhelming the city’s water management system, despite billions of dollars of new investment to fortify roads, buildings, and subways following the devastation of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. That storm left 285 dead and $19 billion in damage to New York City (pdf).

Hurricane Ida was just the latest example. Flooding was worsened by the fact that the ground was already completely soaked from Tropical Storm Henri, which moved through the city less than two weeks before.”The soils were already highly saturated, river levels were already elevated, plus the fact that in the New York metro area there is a ton of concrete,” said Steve Bowen, a meteorologist who assesses the impact of natural catastrophes at Aon, a risk mitigation firm. “It’s infrastructure that’s just not capable of withstanding that volume of water from the sky. It was a lot of really bad things that all came together at the same time.”