The US is delaying China’s dreams of a domestic chip supply chain

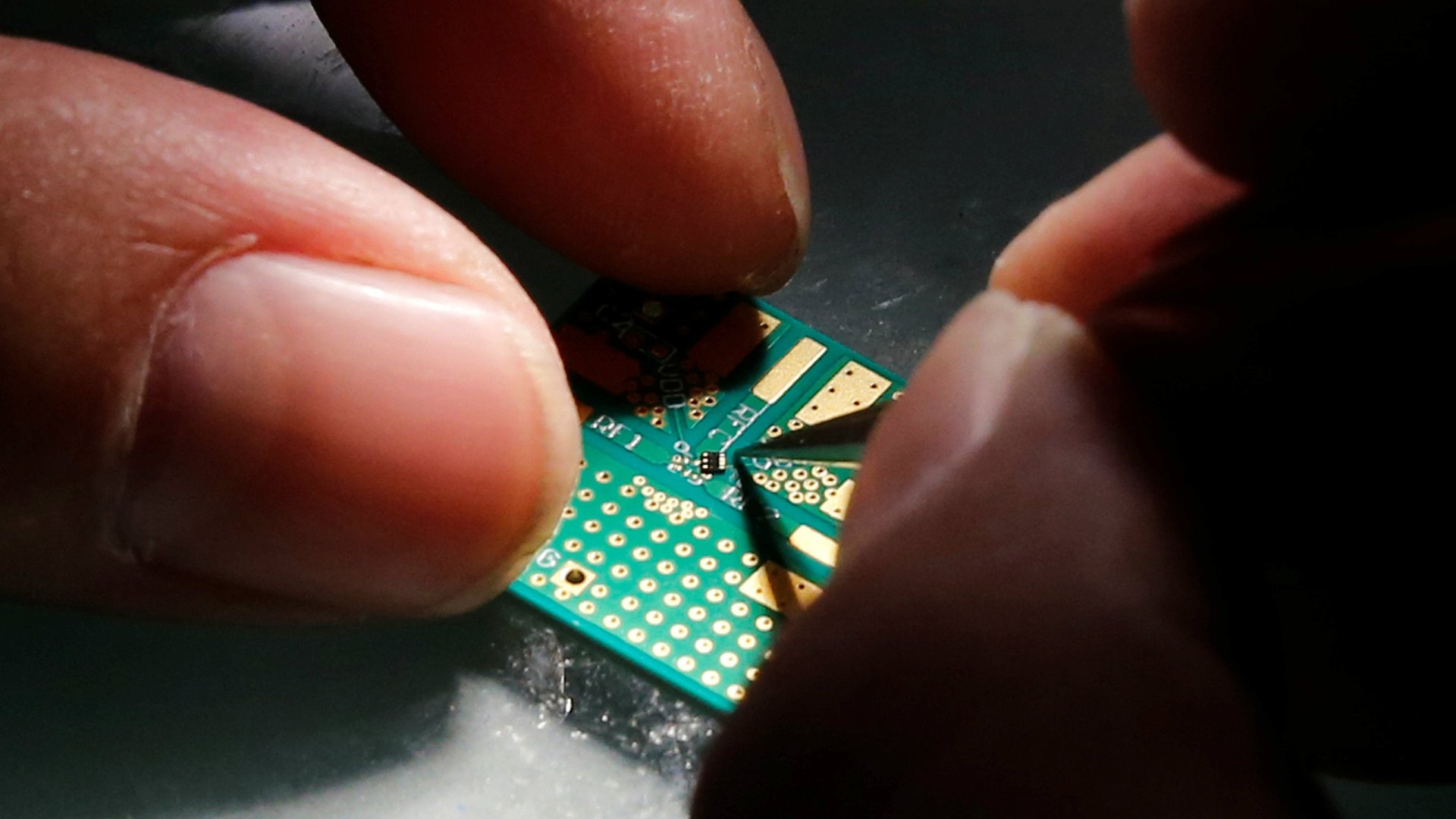

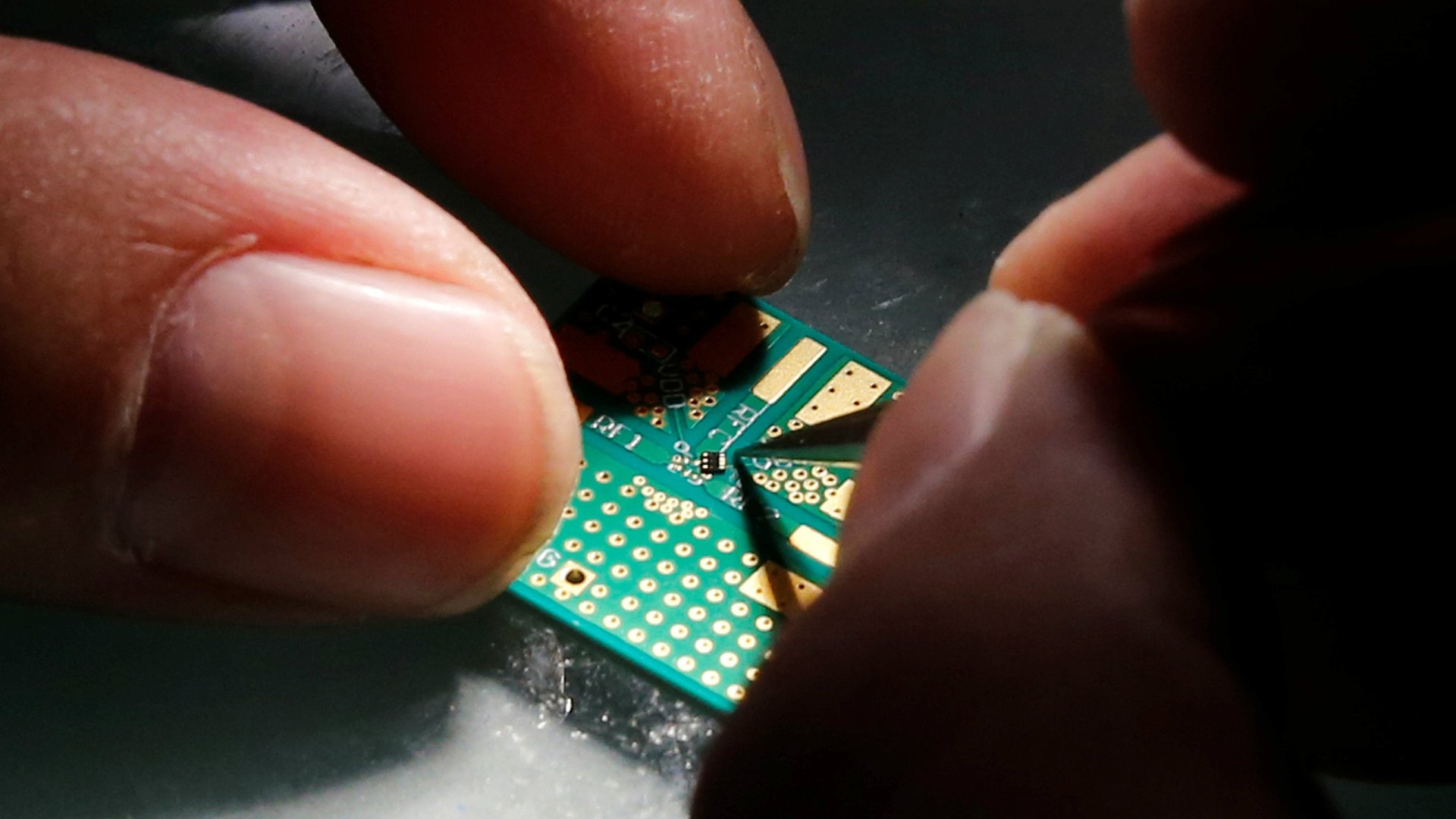

Well before the current chip supply chain crunch, Beijing has been trying to build out a local supply chain for semiconductors—its biggest import item.

Well before the current chip supply chain crunch, Beijing has been trying to build out a local supply chain for semiconductors—its biggest import item.

Tens of billions of dollars of government support (pdf, p. 9) later, China’s chip processing ability is still at least a decade behind the most advanced players. And some of its semiconductor champions in the making are already faltering. On Friday, Tsinghua Unigroup, which began defaulting on its bonds a year ago, said it had accepted a bid from a consortium of state-backed investors to become its strategic investor, which will likely mean ceding control of key assets.

China’s finding out that spending lots of cash can’t quickly build semiconductor self-reliance, especially as the US doubles down on measures such as export blacklists that create bottlenecks up and down the chip manufacturing chain. Last year the US placed China’s largest chipmaker SMIC on the commerce department’s “entity” list, which limits its access to US components, including designs and software, after earlier doing the same to smartphone and telecom equipment maker Huawei, which crippled its chipset design unit.

“Two rounds of export control measures under the Trump administration in 2019 and 2020 have prevented Chinese chipmakers, as well as global foundries that cooperate with Chinese firms, from accessing US-made semiconductor production equipment and software,” wrote Australia’s Lowy Institute think tank in July. “These blockades have seriously constrained China’s ability to pursue technological advancement in the industry.”

The troubles of China’s chipmakers

China’s Made in China 2025 industrial strategy set a goal of having the country supply 70% of its own chip needs by that year. To accelerate the development of the chip industry, China in 2014 set up a state-backed $22 billion integrated circuit investment fund. In addition, many provincial governments established chip-focused funds. In 2020 alone, Chinese chip firms received around $35 billion investment, reported TechNode.

Tsinghua Unigroup, controlled by the prestigious Tshinghua University, was supposed to illustrate how generous subsidies and state determination would help China achieve self-reliance in semiconductors. But its efforts to use its deep pockets to acquire and invest in existing chip firms—which is how it broke into the industry in the first place—have been stymied by US national security concerns deepened in part by the Made in China 2025 plan.

For example in 2015, a plan to buy a 15% stake in Western Digital was abandoned over news that the US intended to examine the transaction for national security risks. Similarly, a $23 billion overture to US chip giant Micron the same year also faced such concerns. Though it continued with other acquisitions, such as its $2.6 billion purchase of French smart chip components maker Linxens in 2018, the US moves slowed its efforts to piggy-back on leading companies with developed businesses. Then it began running out of money.

Last November, it defaulted on a $450 million bond, and by January it had defaulted or cross-defaulted on bonds worth $3.6 billion. The company had 200 billion yuan ($31 billion) in debt as of June 2020, but its cash and cash equivalents stood at only $8 billion in that period, according to its filings and Reuters.

“The group over-leveraged its prestigious name and generous government support…[its] subsidy-fueled fast growth and failure to deliver the high promise of technological progress are emblematic of the major problems of China’s semiconductor sector,” Xiaomeng Lu, director of geo-technology at risk consultancy Eurasia Group, told Quartz in September. A court-led bankruptcy restructuring process had begun in July, at the request of one of its creditors.

On Friday, Tsinghua Unigroup announced that a consortium led by state-backed investors JAC Capital and sister fund Wise Road Capital, which focus on investments in chips and other emerging technologies, would become strategic investors in Tsinghua Unigroup, but provided few other details. A court still has to approve the plan.

Tsinghua Unigroup, JAC Capital, and Wise Road Capital didn’t reply to requests for comment.

Tsinghua Unigroup isn’t the only chipmaker facing financial difficulties. In February, Hongxin Semiconductor, based in Wuhan, began laying off workers, according to Chinese business publication Caixin, just four years after it was founded with a plan to invest $19 billion.

Meanwhile, the US is considering tighter trade restrictions on SMIC, according to the Wall Street Journal, to close loopholes that are allowing some US components for chipmaking to still be sold to it. The company has gained strategic importance due to US actions, securing a $2.2 billion in investment (pdf) from two state chip funds last year.

Money will still flow to chipmakers

Despite these cautionary tales, money will still flow to the sector, which is drawing new players all the time. After all, heavy subsidies coupled with policy determination yielded good results for China’s electric vehicle adoption. Chinese policy lender China Development Bank said in March that it had raised around $30 billion for a new fund focusing on semiconductors.

And certainly heavy investment contributes to the US’s leading position in semiconductors–in 2018 it accounted for 60% (pdf, p. 13) of global semiconductor R&D of $65 billion.

In fact, as stricter government regulation has made investors wary of internet companies, the sector could look even more attractive, despite the massive investment needed and high chance of failure.

“With the recent government regulatory tightening over platform companies, some investors are moving their bets to politically safe areas such as semiconductors, electric vehicles, and biotech. Overcrowding in the chip sector is a significant risk,” said Eurasia Group’s Lu.