Why are steel prices so high when iron ore prices have crashed? Because: China

In the global metals market, a seeming contradiction is playing out.

In the global metals market, a seeming contradiction is playing out.

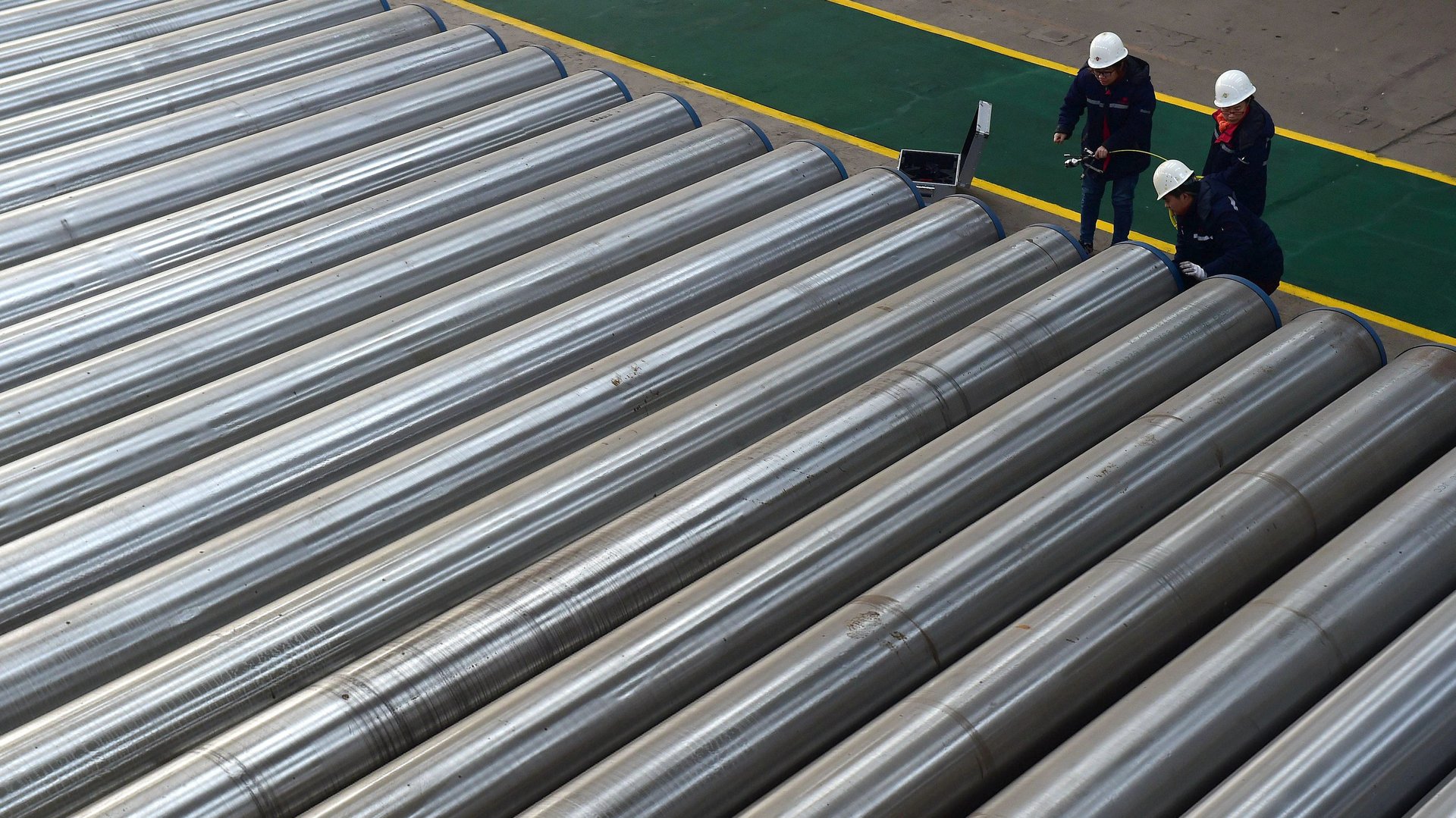

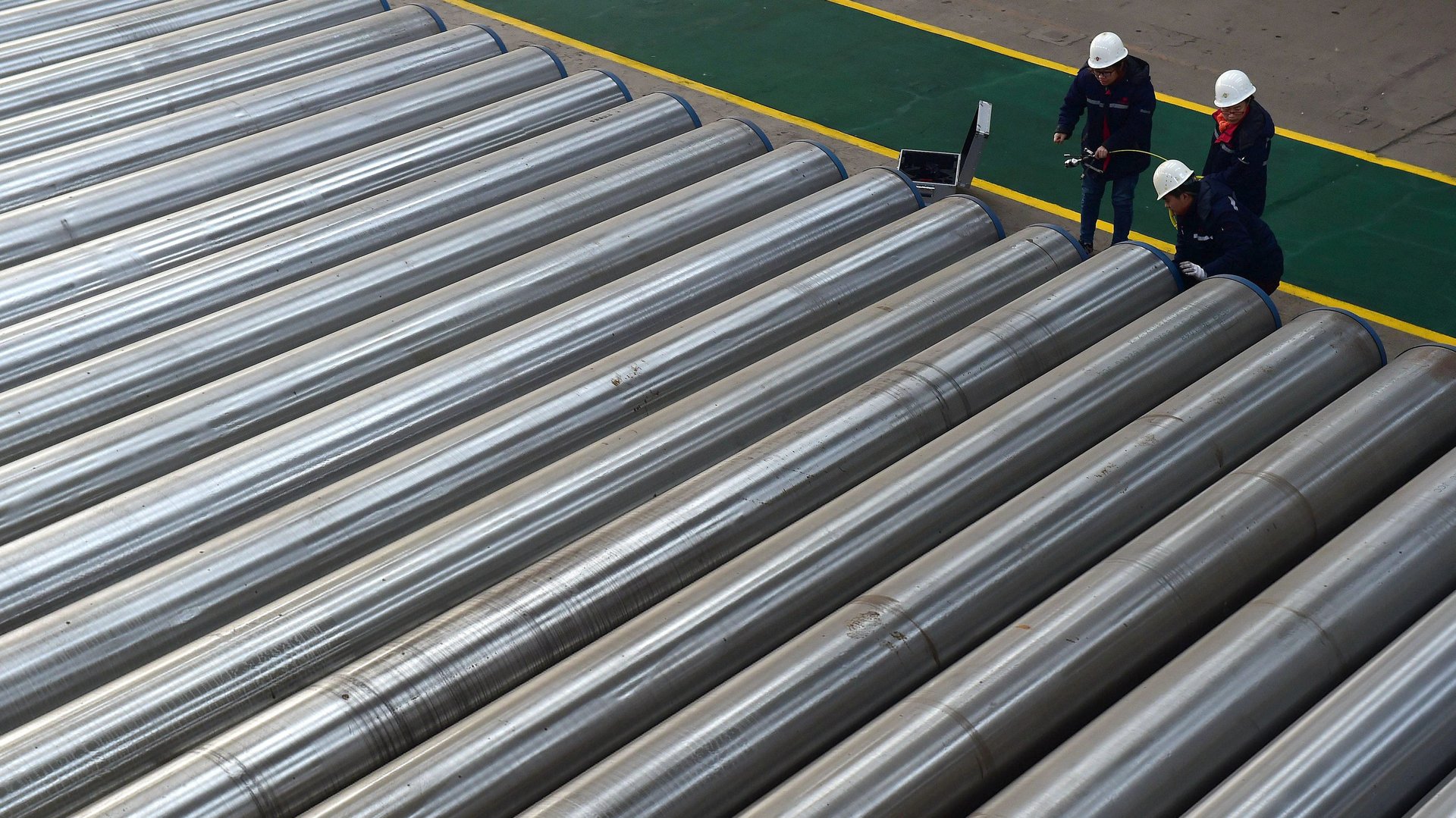

The price of steel has climbed all year; according to one index, the futures price for one ton of hot-rolled coil steel is roughly $1,923, up from $615 last September. Meanwhile, the price of iron ore—the most important ingredient of the steel business—has sunk more than 40% since the middle of July. The demand for the steel is soaring, but the demand for iron ore is in decline.

A number of factors account for the high prices of steel futures—among them, tariffs imposed by the Trump administration on imported steel, and the pent-up demand in manufacturing after the pandemic. But China, which manufactures 57% of the world’s steel, also plans to shrink its output this year, and that is simultaneously acting on the markets for both steel and iron ore.

China is cutting back its steel production

In a declared bid to curb pollution, China is scaling down its steel sector, which produces between 10% and 20% of the country’s carbon emissions. (Aluminum smelters in the country are facing similar restrictions.) China has also raised tariffs on steel-related exports; beginning Aug. 1, for instance, the tariff on ferrochrome, a stainless steel ingredient, doubled from 20% to 40%.

“We expect China’s crude steel production will fall over the long term,” says Steve Xi, a senior consultant at research firm Wood Mackenzie. “As a heavy-polluting industry, the steel industry will remain a key sector in China’s environmental protection work in the next few years.”

The production cuts, Xi observed, are resulting in lower iron ore consumption. Some steel mills, he said, even dumped part of their iron ore inventory, setting off alarms in the market. “The panic extended to traders, and has resulted in the slump we are seeing.”

Mining companies are adjusting themselves to China’s new production targets as well. “The increasing likelihood of stern cuts to steel output in China in the current half year, as affirmed by China’s peak industry body in early August, is testing the bullish resolve of the futures markets,” a vice president at BHP, the Anglo-Australian mining giant, wrote in a late August note about the outlook for 2021.

China’s squeeze of the world’s supply of steel suggests that shortages of many products will continue until the post-pandemic demand and supply stabilize. Car companies, for instance, are already trying to cope with a crunch in the supply of semiconductor chips; a Ford executive told CNBC that steel, too, is now part of a “new crisis” of raw materials.

In 2019, the US made 87.8 million tons of steel, according to the World Steel Association—less than a tenth of China’s 995.4 million tons of output. So while American steelmakers are now making more steel than they have since the 2008 financial crisis, it’ll be a while before they can fill the shortfall that China’s cutbacks will create.