Why your next sweater should be alpaca, not cashmere

Of all the party animals at February’s New York Fashion Week, the alpacas may have been the best-behaved. The lovable, long-lashed camelids mixed with the media at a party where the Peruvian Trade Commission promoted the use of their fiber.

Of all the party animals at February’s New York Fashion Week, the alpacas may have been the best-behaved. The lovable, long-lashed camelids mixed with the media at a party where the Peruvian Trade Commission promoted the use of their fiber.

Those alpacas arrived right on time. The widespread ubiquity of cashmere, the wool spun from soft under-hairs of Asian cashmere (or Kashmir) goats, is no longer sustainable. Sure, cashmere has gotten cheaper since making the leap from luxury to mainstream in the 1990s, but the quality has declined with the price.

In much of the world, sweater weather won’t be here for several months. But production for this autumn’s collections is already underway, and the fashion industry is onto alpaca. Brands such as Louis Vuitton and Versace have already showcased the fiber on runways in Paris and Milan. Numbers on this year’s alpaca sales aren’t yet available, but some designers say their alpaca yarn orders are on wait lists, as mills in Europe and Asia rush to buy up Peru’s supply.

“Especially in the last two years, we have seen an increase in alpaca consumption,” Alejandro Salazar, the sales manager for Michell CIA, the world’s largest supplier of alpaca yarns, tells Quartz. His colleagues are currently preparing orders for clients in Europe, Korea, Japan, and the US, Salazar says, adding that newer customers, including large chains such as Banana Republic and Polo, will have yarns sent directly to factories in China to be knit into sweaters that will hit stores in September.

Like cashmere, alpaca is a natural fiber that looks and feels luxurious, and it can be equally, if not more, durable. And although it’s cheaper than cashmere, the Incas placed a higher value on the fiber than silver or gold—which isn’t really surprising to anyone who has cozied up in a coat or sweater made from the stuff.

Alpacas come in range of more than twenty naturally gorgeous colors, from inky black to warm chestnut and snowy white, and their wool is lofty, soft, and warm. Costello Tagliapietra and Edun took the fabric to another level for fall, brushing woven alpaca to fur-like effect. Those sweaters and coats look and feel every bit as luxe as any cashmere competitor.

The alpaca boom is not only good news for Peru, which exports some $175 million of alpaca fiber each year, and for those of us who get to wear the clothes; it’s also good for the planet. Here are some reasons to choose an alpaca sweater this fall over one made from cashmere:

The cashmere we know today is not sustainable

Simply put, cashmere is environmentally catastrophic. Grasslands in China cannot support the hungry goats required to keep stores stocked with piles of cashmere, and they’re turning into icy deserts.

Prior to the 1990s, cashmere was a rare luxury, but as the fiber has grown cheaper over the last two decades, the demand for ultra-soft, lightweight, candy-colored cashmere sweaters has skyrocketed. (You can buy a 100% cashmere pullover today at Uniqlo for less than $90, and a blended cotton-and-cashmere version for less than $10.)

Goat herds have exploded accordingly. In Mongolia—the second largest provider of the world’s cashmere behind China—the goat population quadrupled from 5 million to 20 million between 1990 and 2009. The majority of those goats reside in the steppe, high plains that are susceptible to extreme cold.

Although those low temperatures help goats to grow the soft down we know as cashmere, unusually harsh winters in recent years have decimated the herds. In the winter of 2009-2010, one of Mongolia’s worst in 30 years, the country lost nearly a fifth of its livestock. The World Bank granted $1.5 million for workers to pile goat carcasses into mass graves.

Ninety percent of Mongolia is already at risk of turning into a desert, and many hypothesize that over-grazing is compounding the effects of climate change in a process that is already underway. Between 1994 and 1999, the Gobi Desert increased by an area larger than the Netherlands.

Because goats are hardier than sheep, herders tend to shift their livestock mix towards goats as land becomes more arid. But that adds to the problem by further damaging the ecology; the goats’ sharp hooves destroy topsoil and grasses and they nibble plants close to their roots, destroying the native grasses. It’s a vicious cycle.

And herded animals aren’t the only creatures in the area. Those former grasslands are also home to endangered snow leopards, wild horses, and Tibetan antelope—all of whose survival have been threatened by the cashmere industry

The environmental footprint of an alpaca is far lighter than a cashmere goat’s—literally

Alpacas live largely in highlands of the Peruvian Andes, for now a less fragile ecosystem, where their soft, padded feet are gentle on the terrain and they graze without destroying root systems. (For a glimpse of alpacas—reputed to be placid, affectionate, and curious as cats—check out this livestream of a Martha’s Vineyard alpaca farm.)

The kind of population boom that cashmere goats have seen seems less likely for alpacas. In spite of fluctuating demand for their fiber, Salazar says the animals’ population in the Andes remains relatively steady. If anything, he worries that the herds will decline as the current generation of alpaca herders and breeders ages, their children are more interested in finding work in the city than continuing their parents’ work. For this reason, Michell owns and operates a breeding ranch and education center to help sustain Peru’s alpaca population.

Alpacas are also more efficient than goats. An alpaca drinks less water than a goat and can handily grow enough wool for four or five sweaters in a year. It takes four goats the same amount of time to produce sufficient cashmere for a single sweater, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Alpaca makes it easy to quit cashmere

None of this would matter to clothing connoisseurs if alpaca products themselves didn’t measure up to cashmere. But they do, especially as cashmere’s quality has declined. After Mongolia’s cashmere industry privatized in 1990, breeders began crossbreeding their herds and focusing on quantity over quality. So goats produced more cashmere by weight, but the fiber became shorter and coarser. The result? A sweater that’s less soft, and more likely to pill. (And what’s the point of buying a fancy sweater if it’s going to look and feel cheap?)

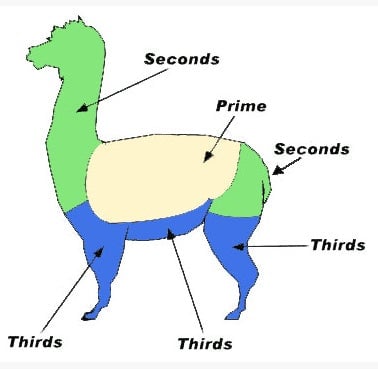

While an alpaca fiber has an overall larger diameter (read: coarser texture) than a cashmere fiber, after animals are shorn, experts hand-sort the wool by staple length and diameter, ranging from prime, downy-soft baby alpaca (those finest of under-hairs, not actually shorn from baby alpacas) to the more robust guard hairs found on animals’ legs and undersides.

Just as certain parts of a cow produce prime cuts, so do specific sections of an alpaca produce prime fibers—and that’s how alpaca yarns are sold. A sweater made of classified “super baby” alpaca can rival its cashmere counterpart when it comes to softness, and outdo it when it comes to strength.

A sweater costing $150 to $200—pretty standard for 100% alpaca—may seem expensive, but it can be a good investment. Whereas cashmere fibers over four centimeters in length are considered long, alpaca fibers commonly measure between eight and twelve centimeters—so are far less likely to pill, and longer-lasting. And with consumers in the US generating about 14 million tons of textile waste each year (about 385,000 tons of clothing are tossed annually in the UK), it’s better to buy a single great, durable sweater than a pile of highly replaceable ones.

Unlike cheap cashmere, alpaca feels stylish and substantial. Knowing that it’s also relatively sustainable might be the ultimate luxury.