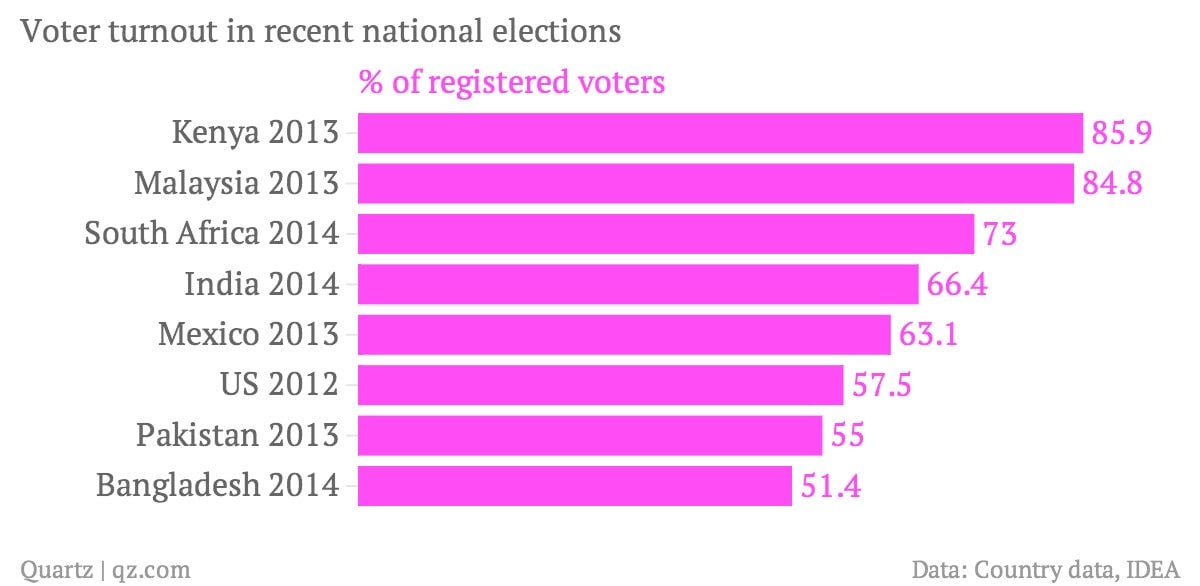

Here’s how India’s record-setting voter turnout compares to the rest of the world

Voting closed May 12 in India’s massive general election, with 540 million voters—66.4% of those eligible—going to the polls, according to the Election Commission. This was a new record for India, and up from 58% in 2009. The impressive turnout handily beat the previous high in the 1984 election after prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated. Her son Rajiv was elected with 64% of voters going to the polls.

Voting closed May 12 in India’s massive general election, with 540 million voters—66.4% of those eligible—going to the polls, according to the Election Commission. This was a new record for India, and up from 58% in 2009. The impressive turnout handily beat the previous high in the 1984 election after prime minister Indira Gandhi was assassinated. Her son Rajiv was elected with 64% of voters going to the polls.

South Asia’s recent elections have all been marked by high voter turnout, relative to expectations and historical figures. In neighboring Pakistan, turnout was 55%, significantly higher than 35% in 1997, as a sign of the populations’ defiance of growing pressure from religious fundamentalists. About 58% of registered voters are believed to have participated in Afghanistan’s recent election, despite Taliban threats.

Higher voter turnout is often linked with voters’ belief in the political process and a desire for a change of government. Research shows a correlation between a high turnout and anti-incumbency, in India and the US.

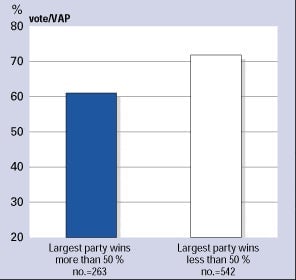

Other factors, including literacy rates, population size or average income, have a limited impact on voter participation rates, the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance found. But the group cites one “clear link” to high voter turnout—the competitiveness of electoral politics in a political system, a factor this Indian election certainly had plenty of. In a situation where the largest political party was expected to win more than 50% of the vote, turnout was, on average, 10 percentage points lower than it was not:

In contrast to India’s high turnout, and that of other recent elections in emerging markets, voter participation in developed nation elections is declining. In Europe, for example, it has dropped by 10 to 15 percentage points since the 1980s. Just 57.5% of eligible US voters turned out for the last presidential election, and just 53.8% of Canadians voted in the last federal election, perhaps due to “disillusionment or indifference,” the Conference Board of Canada notes.

There may be no shortage of skepticism about what a new Indian government can actually accomplish, but at least indifferent voters were scarce.