US states and cities are already making big plans for the $1 trillion infrastructure bill

The US Congress and president Joe Biden have signed off on a $1.2 trillion infrastructure deal. Now states and cities must decide exactly how it will be spent.

The US Congress and president Joe Biden have signed off on a $1.2 trillion infrastructure deal. Now states and cities must decide exactly how it will be spent.

Over the next five years, most of the money will trickle down to states and cities through funding formulas and competitive grants, it will be up to these local authorities to plan and execute specific projects. Various sums are earmarked for different purposes: roads and bridges, ports, broadband.

Many of these projects don’t yet exist. But in some places, public officials are already prioritizing projects the federal money could fund right away. Some infrastructure is already under construction, while other is “shovel-ready,” planned but awaiting funding. Analysts expect these projects to see the most immediate benefit.

“State and local leaders who are ready to hit the ground running will be in the best position to maximize this federal funding,” says Joseph Kane, a fellow at Brookings Metro studying infrastructure.

Roads, bridges, and highways are first in line. State and local transportation authorities, arguably, have the most projects ready for federal funding. But the bill is much bigger than repairing roads. Officials across the country are starting to plan for how the funding can support new infrastructure projects to usher in a new generation of railways, ports, public transit, natural resource areas, and more.

Regional transit takes the train

Amtrak, America’s national passenger rail service, is set to receive a large share of the bill’s $66 billion investment in railroads. It has announced plans to possibly expand service to 160 more cities. Among these is a longstanding hope for an intercity train connecting Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana’s two most populous cities. Plans have been in the works since 2014 when a study mapped out the exact route and estimated cost. The proposed line has garnered public support since then, but hasn’t had sufficient funding until now. While the infrastructure bill didn’t explicitly prescribe train lines that should be built, Baton Rouge and New Orleans were named in the text as an example of the “city pairs” that would benefit from interconnection.

California is hoping to use some of the new funding to make incremental progress on its regional bullet train project that has been ongoing since 2008. The plan to build a train from San Francisco to Los Angeles has been hampered by schedule delays and cost increases. As of now, construction has only begun on a segment of the train in the Central Valley, but plans for the entire system have been approved, and the California High-Speed Rail Authority has identified specific competitive grants in the bill that it is prepared to compete for.

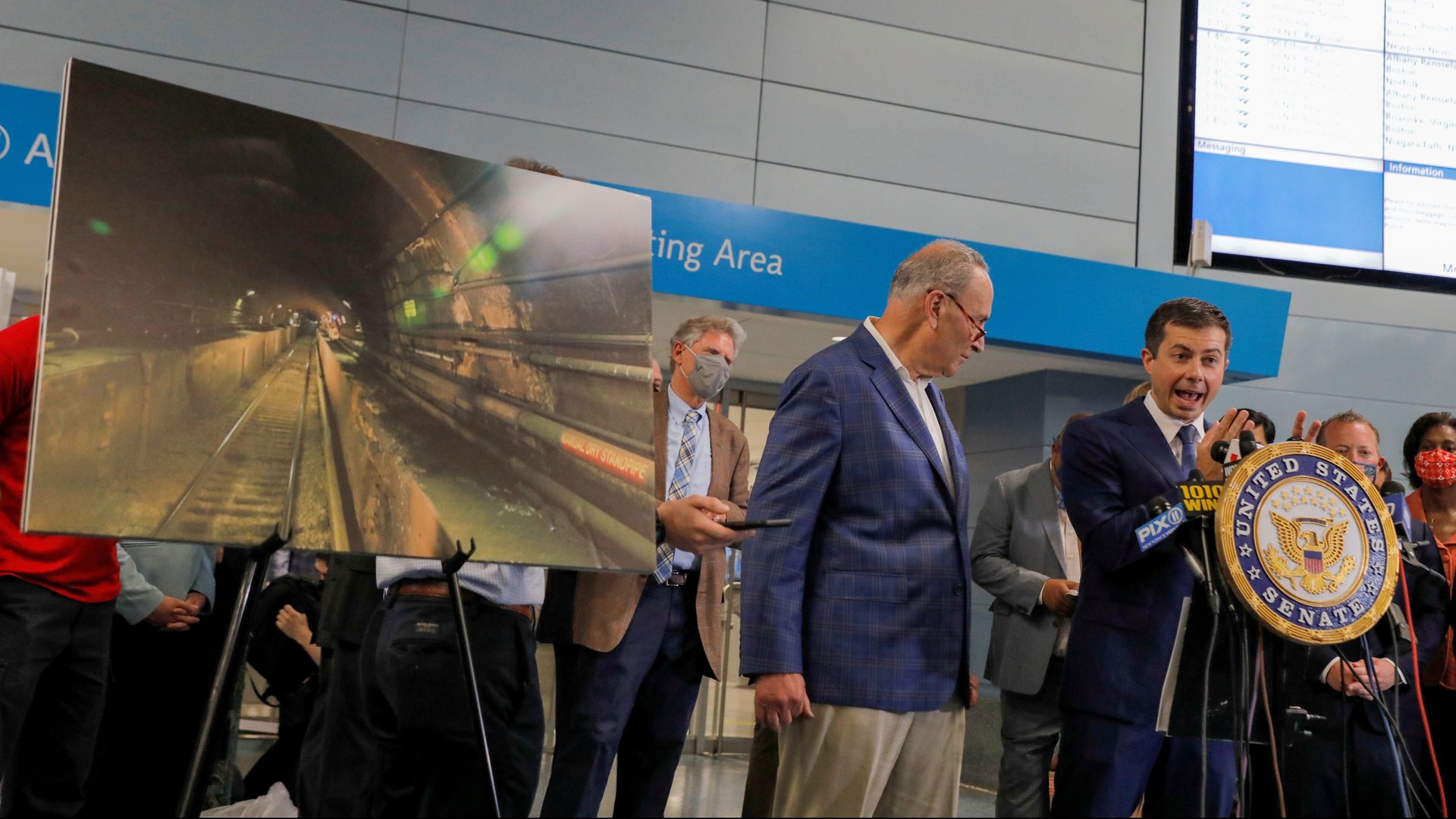

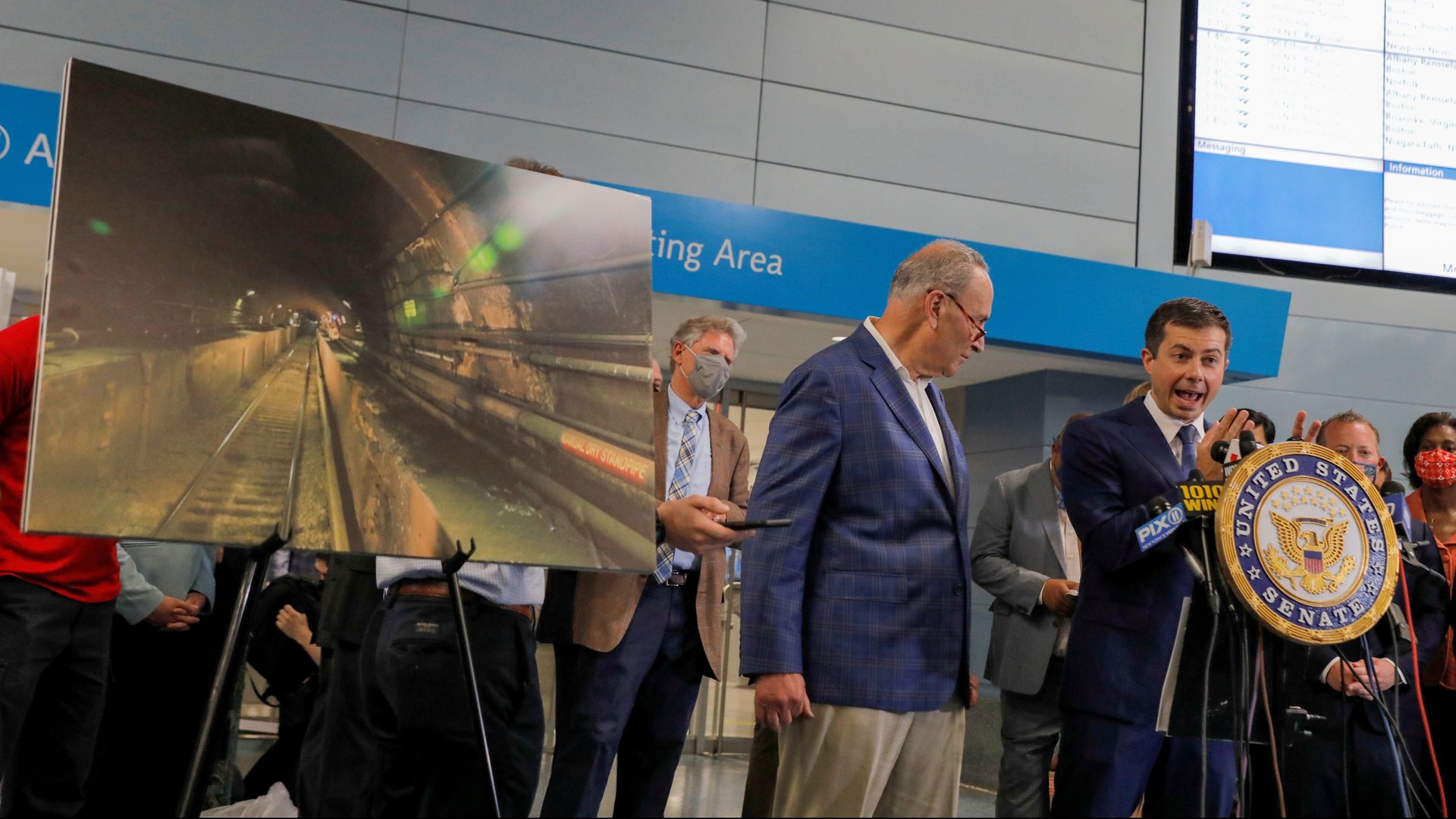

Urban rail transit is on the fast track

Austin is planning to use infrastructure funds to help build a new light rail transit system. Last November, voters overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure for a property tax increase to fund the initial stage of the $7 billion project that includes two new light rail lines, an underground tunnel, and expanded bus service. But the project will receive nearly half of its funding from the federal government, and the city has been vocal with the Biden administration about getting infrastructure bill funding since the beginning of the year. Mayor Steve Adler even spoke to transportation secretary Pete Buttigieg about the project.

Other places are using the bill to expand mass transit systems as well; Tampa, Florida wants to expand its streetcars line, which currently serves about 68,000 riders. New York City also has a laundry list of infrastructure projects for its subways, tunnels, and commuter trains that the area’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority expects will get a boost from new funding. They include a new tunnel from New York to New Jersey, and the biggest expansion of the subway system in 50 years.

Money is flowing into natural infrastructure

Eight billion dollars in the bill are dedicated to “Western water projects” to help states like California, Nevada, and Colorado shore up water systems depleted by drought. This includes $1 billion in funding for water recycling programs, which treat wastewater to make it safe again for consumption. A handful of US communities have established water recycling programs, and even more, like Los Angeles and its surrounding area, and Colorado Springs are developing plans for them. The southern California water treatment facility is still in its early stages, but once scaled up out could serve more than 500,000 households.

Other specific provisions in the bill for natural infrastructure include $24 million to support the restoration of wetlands near San Francisco. In Virginia, a federal program to restore the Chesapeake Bay has gotten a $328 million boost.