The best and worst countries at middle management

Led by Stanford’s Nicholas Bloom, researchers have spent a decade collecting survey data from managers to try and explain why certain companies and countries produce so much more. Good management plays a huge role. About a quarter of the productivity gap is explained by how managers do their jobs, according to a new NBER paper presenting the most recent results.

Led by Stanford’s Nicholas Bloom, researchers have spent a decade collecting survey data from managers to try and explain why certain companies and countries produce so much more. Good management plays a huge role. About a quarter of the productivity gap is explained by how managers do their jobs, according to a new NBER paper presenting the most recent results.

The survey doesn’t measure inspirational leadership, great dealmaking, or innovation. But it does measure the behaviors most directly tied to getting more and better work done.

The survey asks managers whether they monitor employee behavior and output and use that information to improve. It asks if they set targets and take action if the targets aren’t met. And finally, the survey asks whether companies promote and reward people based on performance (rather than tenure).

The survey was designed because Bloom and his colleagues noticed that there was very little hard data on managerial ability, despite its importance. It was also a response, in part, to the way that management is usually taught, with case studies that typically focus on successful executives at big companies and rely heavily on anecdotes.

The survey is double-blind, and targets senior level middle managers, who have a full overview of management practices but aren’t detached from daily operations. The full list of questions asked is available here. (pdf)

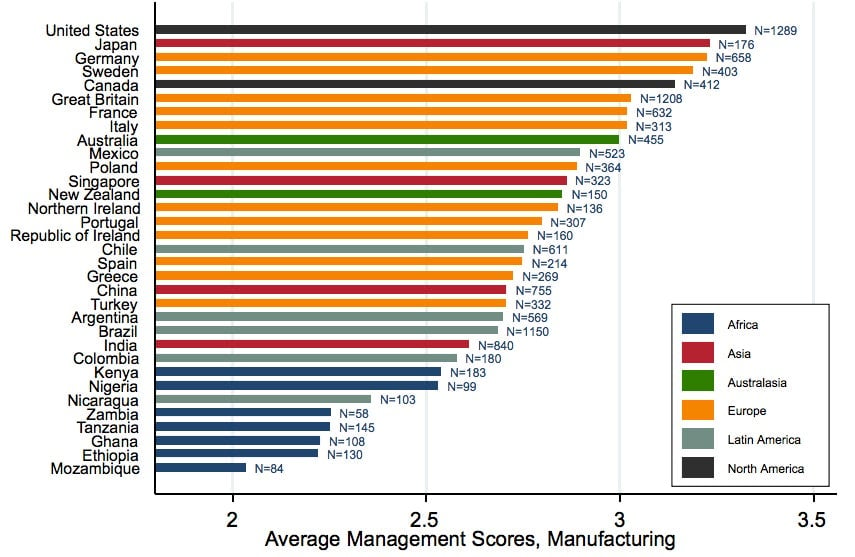

Here’s the most up to date ranking of the average scores of manufacturing managers on the survey questions (each response gets a score ranging from 1, the lowest, to 5, the highest), including survey data through April 14th. United States managers come in first, as they do in the hospital and retail sectors, as well. The rankings closely approximate national income and productivity ratings:

The US doesn’t lead everywhere. The country is nearer the middle of the pack for schools, where the UK and Sweden come in front.

A key difference between the highest and lowest scorers is that a country like India, for example, has a much higher percentage of firms with very low management scores. It means that a lot of resources are going to poorly managed plants. In contrast with the United States, it takes a long time for poorly managed firms to shrink or exit the market.

One of most important conclusions is that management practices can change. The authors offered free consulting help on the key deficits measured in the survey to Indian manufacturers. Where firms accepted the offer, they were able to significantly boost management scores, profits, and productivity in a relatively short time compared to a random set of control firms.

In just about every country, managers at subsidiaries of multinational companies scored consistently high. That’s an indication that country specific problems can be overcome, and good practices spread.