Billionaire Wilbur Ross joins the market move back to SPACs

Billionaire Wilbur Ross has launched a special investment vehicle, which had been popular just before the financial crisis gripped the markets, to make opportunistic acquisitions. The prominent investor, who carved out a reputation restructuring troubled companies in the ’80s and ’90s and then launched his own private equity firm 14 years ago, has submitted a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission to form a so-called special purpose acquisition corporation (or SPAC). The deal marks Ross’s first SPAC, sources familiar with the matter say.

Billionaire Wilbur Ross has launched a special investment vehicle, which had been popular just before the financial crisis gripped the markets, to make opportunistic acquisitions. The prominent investor, who carved out a reputation restructuring troubled companies in the ’80s and ’90s and then launched his own private equity firm 14 years ago, has submitted a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission to form a so-called special purpose acquisition corporation (or SPAC). The deal marks Ross’s first SPAC, sources familiar with the matter say.

Otherwise known as “blank check” companies, SPACs are curious entities. They seek to raise money through the public markets, similar to how a private company like Alibaba or Twitter would raise money in order take itself public through an IPO. One fundamental difference is that these SPACs are essentially shell entities looking for one or two big investment targets. Just for context, one of the most notable SPAC companies is Burger King, which had been taken private through a leveraged buyout by 3G Capital back in 2010, and was then acquired by a SPAC called Justice Holdings in 2012. (Justice Holdings is run by another billionaire investor, Nicolas Berggruen, and British financier Martin Franklin.) Some recent SPACs have been led by the likes of former Barclays CEO Bob Diamond, whose fund is targeting African financial companies.

Ross’s SPAC was filed discreetly several weeks ago as part of the JOBS Act (a rule meant to encourage small companies not quite ready to subject themselves to the scrutiny of an IPO to go public sooner), according to sources. But the filing for the SPAC, known as WL Ross Holding Corp., only became public officially on May 9, to little to no fanfare. Ross is looking to raise upwards of $400 million through various investors—mostly institutional investors like mutual funds and multi-strategy hedge funds—sources say. Deutsche Bank and Bank of America are underwriting the offering. Ross hasn’t yet responded to a request for comment. (UPDATE: Ross declined to comment.)

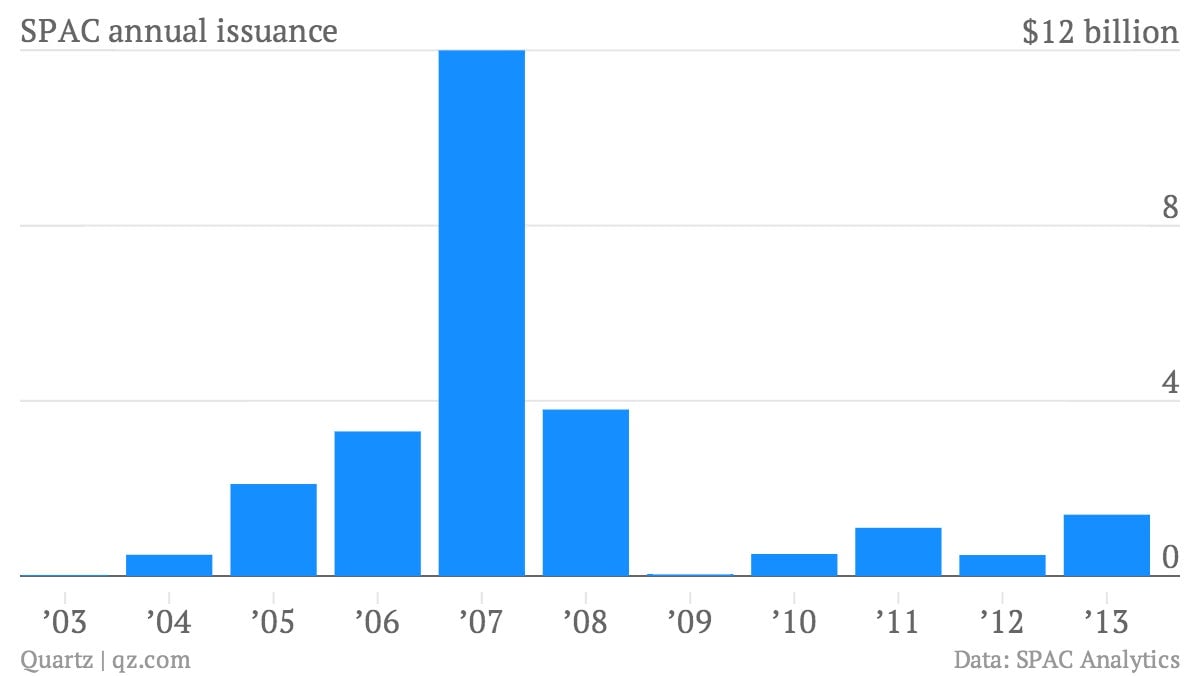

In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, SPACs have been experiencing a resurgence of sorts. According to industry data site SPAC Analytics, last year’s issuance volume for SPACs hit its highest levels in five years at $1.4 billion. (The site still doesn’t have data on 2014.) That still pales in comparison to the $3.3 billion issued in 2008 and the whopping $12 billion in SPACS that were brought to market in 2007.

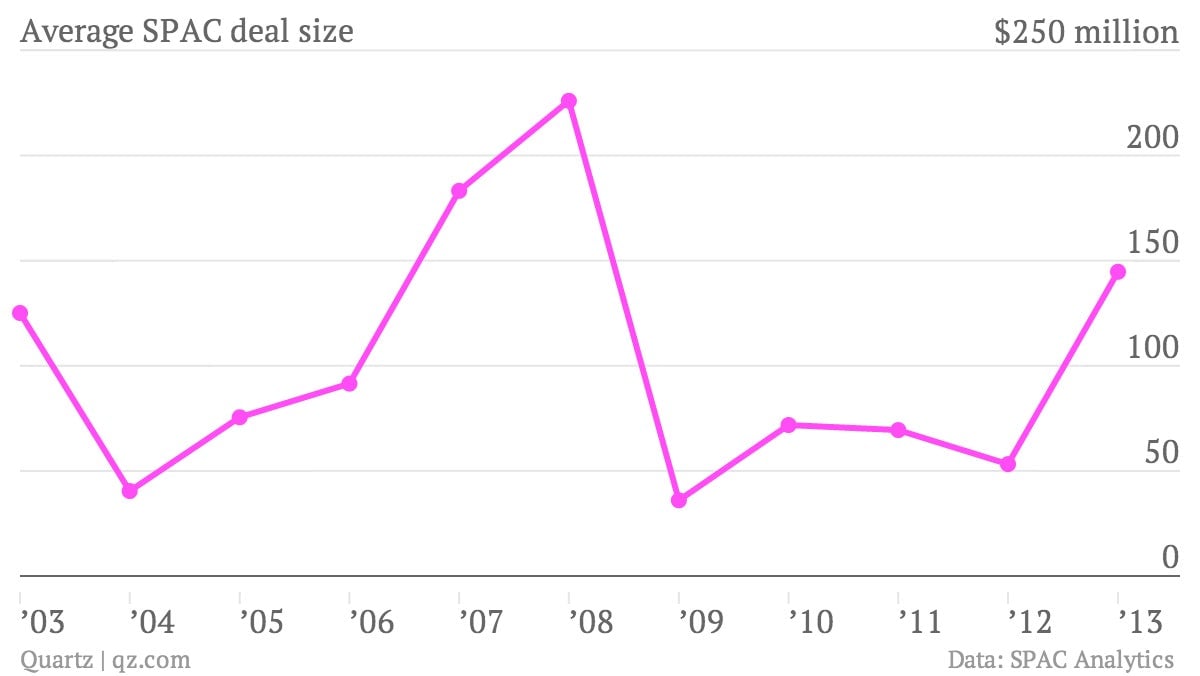

But average deal size for SPACs is also picking up. It hit its highest level in six years in 2013 with an average deal of roughly $145 million, compared to $183 million in 2007.

Why are SPACs growing again? For one thing, stock markets continue to do well, making it easier for SPACs to get the funding they need by selling shares. Strong stock prices also are important to SPACs because these entities use their own stock to buy companies. This only works when stock markets are performing well. With a combination of cash and stock, Ross’s SPAC may be able to purchase or take an ownership stake of more than $2 billon, sources familiar estimate.

There are a few more details to know about how SPACS work. The New York Times’ Andrew Ross Sorkin does a good job of explaining their structure in an article from the SPAC heyday (paywall) in 2008. But in essence, the SPAC will have a specific timeframe, in this case 24 months from the closing of a deal, to identify an investment or be forced to return the cash to investors. There’s no guarantee an investment will be identified in that time span, which is one of the most glaring risks of investing in a SPAC. If an investment isn’t targeted, the money must be returned, with the SPAC deducting capital for expenses like operating the investment vehicle.

In this way, SPACs are similar to private equity structures, where investors pay a fee for a manager to run an investment fund. No word on exactly what Ross’s new investment vehicle would be interested in buying. (He’s previously invested broadly in industries as different as financial services and steel companies.) Investors will likely want to know a bit more too, when discussions with prospective shareholders happen over the next month.