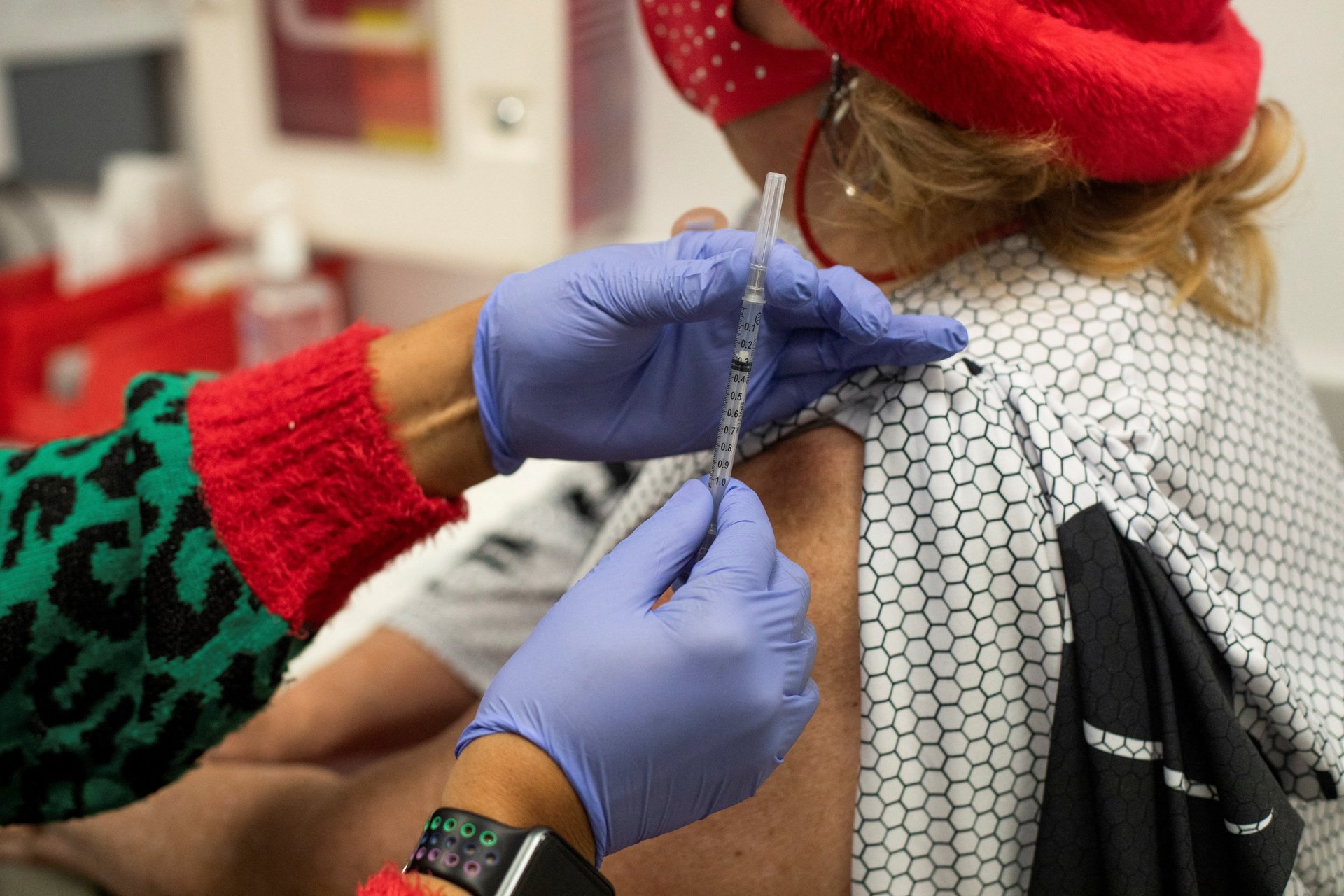

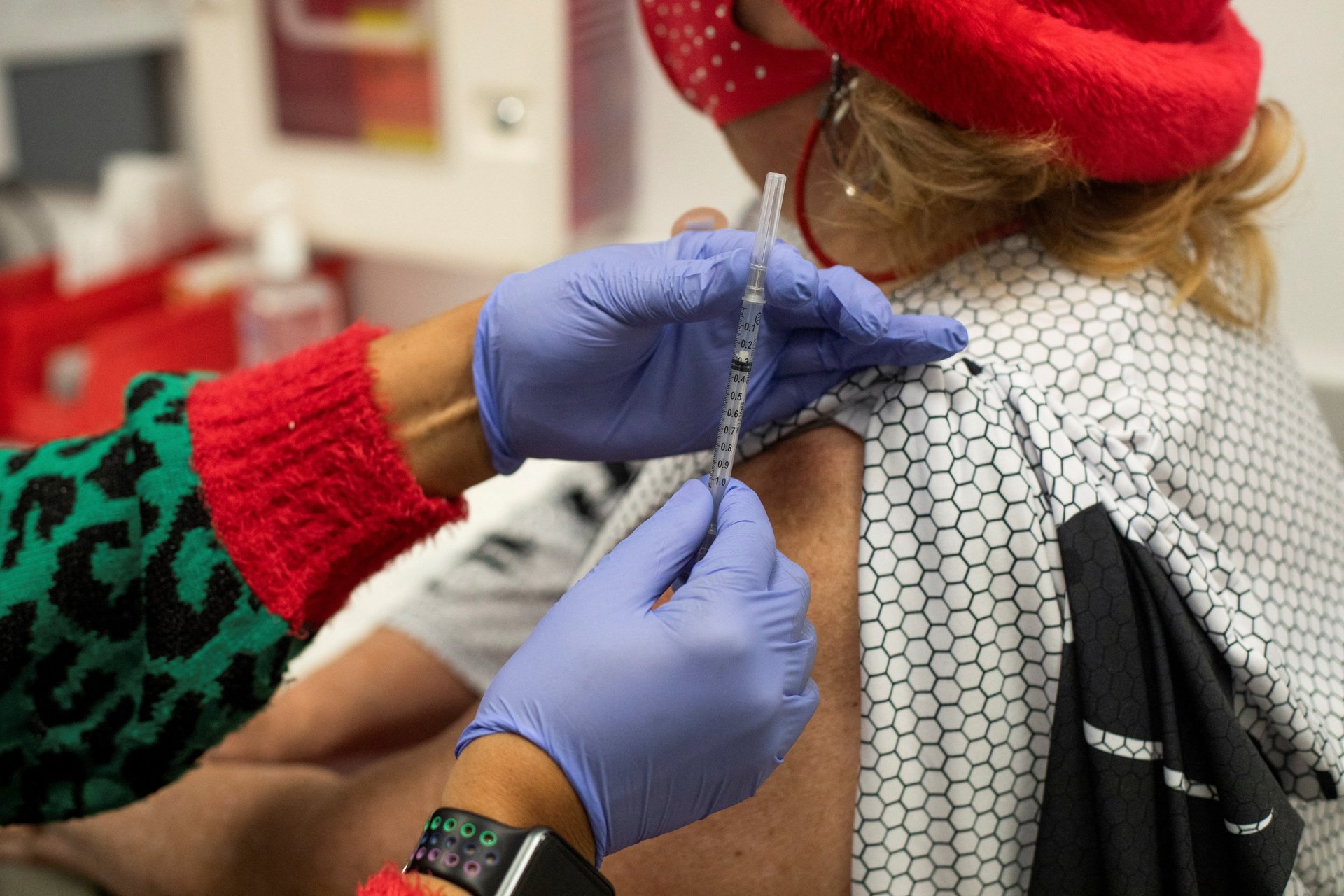

The US military is testing a vaccine designed to protect against all covid variants

The US military is testing a vaccine that could be effective against all variants of covid-19, completing preclinical trials that shows it protected primates against multiple variants as well as covid’s cousin diseases like SARs.

The US military is testing a vaccine that could be effective against all variants of covid-19, completing preclinical trials that shows it protected primates against multiple variants as well as covid’s cousin diseases like SARs.

The scientists at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) received the DNA sequence for covid in early 2020 along with the rest of the world, but instead of focusing on a vaccine that just targeted that strain of covid, they decided to work on a vaccine that would be effective against all variants of covid. The vaccine is part of the institute’s “pan-SARs” strategy that aims to produce vaccines for this pandemic and future pandemics.

The Spike Ferritin Nanoparticle (SpFN) covid-19 vaccine went under successful animal trials earlier this year and the phase 1 trial results had positive results that are under review, Kayvon Modjarrad, director of WRAIR’s infectious diseases branch, told Defense One, a news outlet that covers the US military. After Defense One published the news, WRAIR issued a press release noting that the vaccine had not yet been tested against omicron. Typically phase 1 trials test that vaccines are safe and elicit antibodies.

The SpFN vaccine, named after a protein called ferritin, will need to undergo phase 2 and phase 3 trials where the researchers can determine its efficacy and how it works in already vaccinated and previously sick individuals. WRAIR is working with an unnamed industry partner to produce vaccines for the next trials and for the broader public if the vaccine proves effective and is approved by regulators.

The search for a panacea covid vaccine

A universal, variant-proof vaccine for any disease is the holy grail for vaccine scientists. Researchers have hoped for a universal flu vaccine for decades.

Researchers pursuing a universal covid vaccine generally have two options, said Eric Topol, director of the Scripps Research Translational Institute. They can reverse-engineer multi-potent antibodies in the wild which are developed in less than 0.1% of the population that’s been infected or they can create synthetic antibodies after exploring the 30,000 genetic bases within the virus and predicting how it might mutate. WRAIR researchers seem to have opted early on for a synthetic approach to locating these antibodies.

The crunch that scientist run into is in trying to elicit these antibodies in everyone else, said Duane Wesemann, an immunologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

“So let’s say we discover that we can elicit that in humans, but the challenge is how do you elicit enough of that particular antibody to make it effective and then how do you make it last long,” Wesemann said.