Why house prices are a problem for the government, not central banks

House prices in the UK are once again on the rise. Over the country the average price in March stood at £169,124 ($204,805), some 5.6% higher than a year earlier. In London the gains were even more marked with the average property price rising to £459,000 ($772,956)—more than 10 times average household income.

House prices in the UK are once again on the rise. Over the country the average price in March stood at £169,124 ($204,805), some 5.6% higher than a year earlier. In London the gains were even more marked with the average property price rising to £459,000 ($772,956)—more than 10 times average household income.

Are housing “bubbles” a central bank problem?

Concerns over a possible housing bubble have begun to put pressure on Bank of England’s Governor Mark Carney. In his opening remarks ahead of the release of this month’s Inflation Report he moved to reassure critics that the Bank could rely on its prudential toolkit to monitor the housing market.

Not everyone is convinced. Andrew Sentance, a business economist and former Monetary Policy Committee member, warned on his blog that the strength of the housing market boom required firm action from the Bank in the form of rate rises. Restricting lending through tighter mortgage conditions, he warned, would equal to a “retrograde step [that] will deny many first-time buyers their first step on the housing ladder”.

So is Sentance right to suggest that Carney is taking a big risk by not raising rates now to cool house prices?

I’m not convinced. It is certainly the case that prices are rising at a far more rapid rate than we have seen in recent years, but that may reflect pent-up demand from buyers who have been locked out of the market in recent years. If so, we might expect prices to rally sharply but then begin to ease off as this catch-up demand effect drops off.

Moreover, there have been reports from estate agents that recent geopolitical uncertainty (for example the crisis in Ukraine) may increase foreign capital flows into the country looking for safe haven assets like prime property. This too may prove to be a temporary effect subject to reversal if the situation improves.

Yet none of this really answers the question of whether property price rises should really be the major concern of central banks. After all, the systemic risk of a runaway housing market is posed by lax lending, not by the prices themselves. That is, although worsening housing affordability can have significant social costs, if the market is being driven by, for example, domestic or foreign cash buyers then it is unlikely to become a financial stability problem.

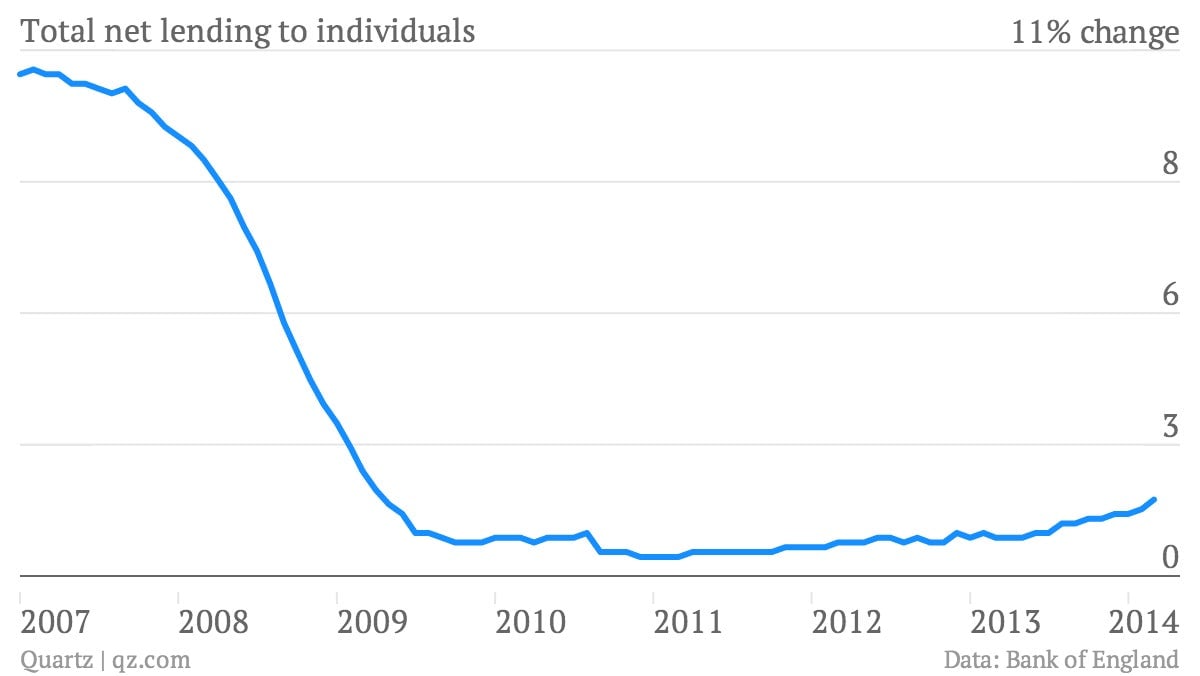

As the chart below shows, although it is undoubtedly true that monthly net lending in the UK is creeping upwards, it is still far below the levels we saw before the crash:

Giving macro-prudential oversight some teeth

That does not suggest the Bank can afford to be blasé about the risk of rising house prices. However, it does indicate that it would likely be premature for the MPC to use a blunt tool such as raising the base rate when it also risks making borrowing more expensive for small businesses and increases the interest burden on indebted households.

Furthermore though their effectiveness is untested, the macro-prudential tools at the Financial Policy Committee’s (FPC) disposal can be directly targeted at riskier lending (such as high loan-to-value mortgages or repayments that account for a large percentage of the borrower’s income). If the committee is to have any meaningful role in promoting financial stability then they should surely be used first before more traditional monetary policy levers are pulled.

Were the FPC to become increasingly worried about tight housing supply and rising prices, they might also decide to ask the Coalition government to scrap their Help to Buy scheme. Under it, the government has taken a 20% in 19,394 house purchases with high loan-to-value mortgages as at the end of March, with current plans for a further 25,000 purchases a year until 2020.

Seen by many as a ploy to provide a quick boost to household morale heading into the General Election next year, it could become a key test of the effectiveness of the new responsibilities handed to the Bank in the wake of the crisis.

Propping up the housing market by using the state’s balance sheet to massage affordability is hardly likely to be a long term solution. A combination of increasing housing supply in high-demand areas like London and a coherent policy for regenerating regions outside of the capital, to ensure that existing housing stock is fully exploited, will ultimately be required. Ultimately, however, this relies on the government designing and committing to a coherent long term housing policy including a rationalization of planning laws as well as direct state intervention to rebuild depleted social housing stock.

Given the fragility of Britain’s nascent economic recovery managing the exit from extraordinary monetary policy was always going to be a challenge. The nature of that recovery may make it even more of one that policymakers imagined—but central bankers should be wary of calls to correct yesterday’s imbalances.