2021 was the year supply chain managers became cool

For supply chain managers, 2021 was the year their job became cool. Work once relegated to the dry, party-killing details of cargo schedules and warehouse management became the gripping headline sagas of snarled transport webs, clogged ports, and ships stuck in the Suez. The very phrase “supply chain” stopped being jargon and started being the deciding factor between a gift-filled Christmas and one marred by IOUs.

For supply chain managers, 2021 was the year their job became cool. Work once relegated to the dry, party-killing details of cargo schedules and warehouse management became the gripping headline sagas of snarled transport webs, clogged ports, and ships stuck in the Suez. The very phrase “supply chain” stopped being jargon and started being the deciding factor between a gift-filled Christmas and one marred by IOUs.

The crisis also served as powerful advertising for business schools that offer supply chain programs. “It was a topic that students never understood until they’d had a few years of work experience,” said Kevin Linderman, the chair of the supply chain department at Pennsylvania State University’s Smeal College of Business. “But now, with all the discussion in the news, it’s become a part of the lexicon. Students, especially undergraduates, are coming in with some idea of what it is.”

As a specialization, supply chain studies never had the lucrative allure of finance or the pizazz of marketing. Now, though, the field is having its moment in the sun. And administrators like Linderman are seeing a recognition of the importance of these courses—from students as well as from companies.

In 2020, when Smeal’s undergraduates declared their majors, the number who picked supply chain management rose 20% compared to the previous year. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Supply Chain Management department, part of the university’s Center for Transportation & Logistics, more than 60% of the class scheduled to graduate in May 2022 had already received job offers by the end of 2021, compared to 55% in 2019 and 29% in 2020.

In the first year or so of covid, given the uncertainties, prospective students were reluctant to spend money on a new course, so enrollment was shaky, said Maria Jesus Saénz, the executive director of MIT’s master’s program in supply chain management. Companies, too, were temporarily unsure of hiring students. But now, Saénz said, “the students are coming, and the companies are coming as well.” Everyone’s confident that the supply chain disruptions that made headlines in the past two years won’t be the last.

Everybody wants a supply chain czar

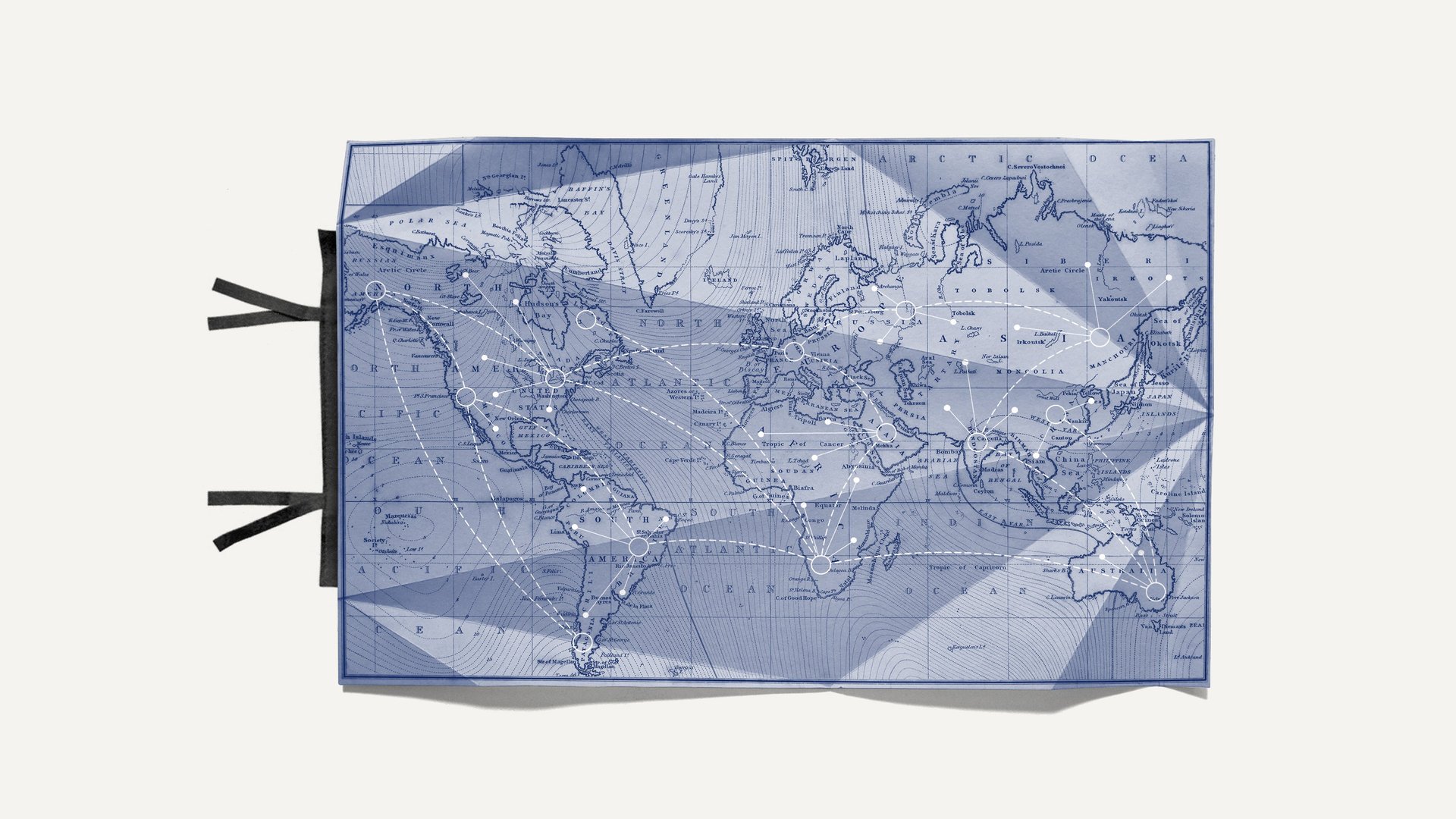

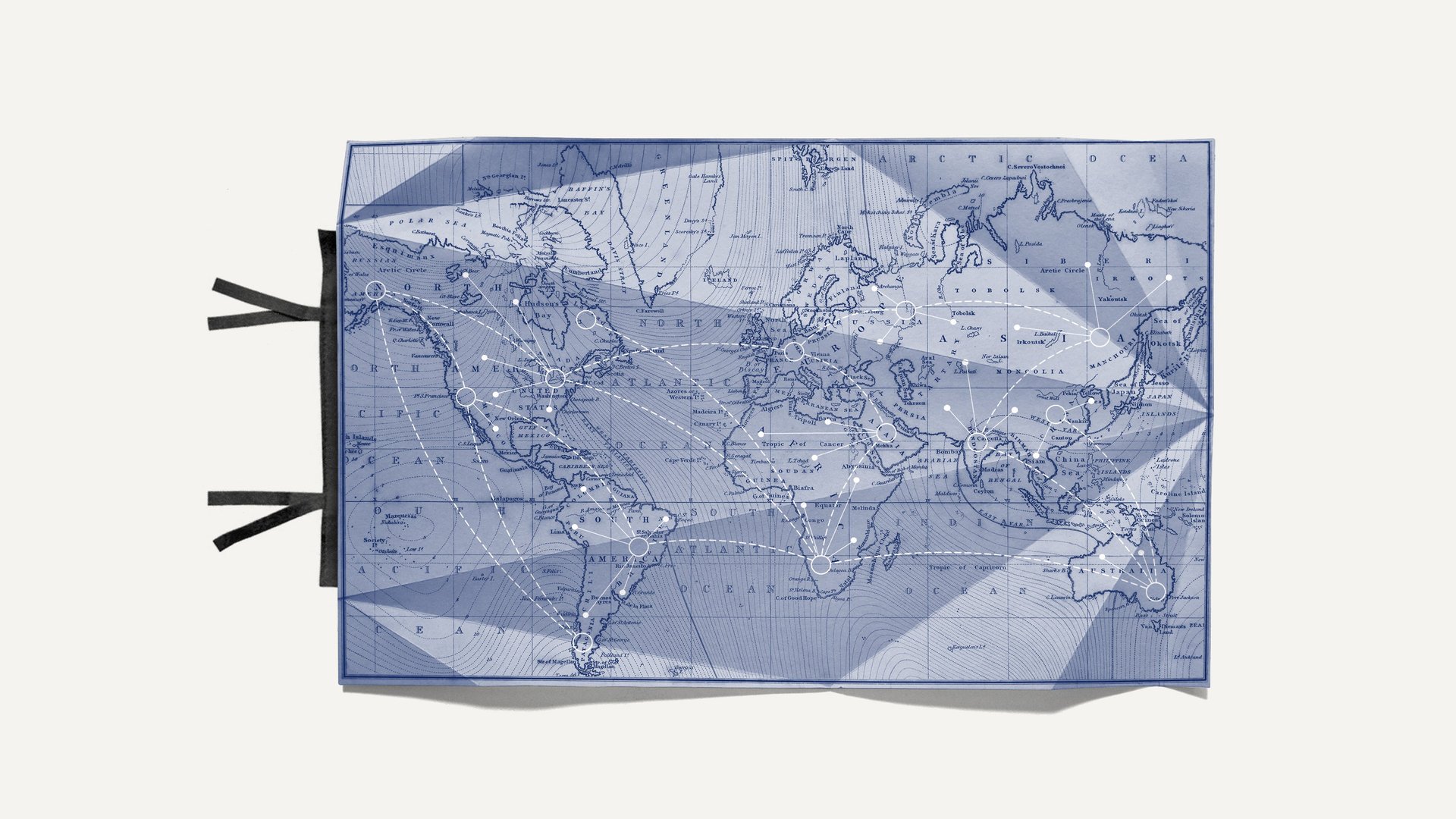

The term “supply chain management” was coined by a Booz Allen Hamilton consultant in 1982, but the academic discipline, under other names, was far older. Syracuse University offered a major named “Transportation” back in 1921 that dealt with the same subject matter. Companies have always needed to get products from one place to another, after all; the Booz consultant was merely giving the science a new, holistic name.

Even into the 1990s, “supply chain” wasn’t a popular term, said Abe Eshkenazi, the chief executive of the Association for Supply Chain Management (ASCM). It was called operations management or business logistics, Eshkenazi remembered, “and there were only half a dozen or a dozen designated supply chain programs in the world.” Then, as outsourced manufacturing became more common, and as businesses spanned an increasingly globalized world, navigating complex supply chains became an indispensable skill.” Now you have more than 500 schools offering supply chain programs,” Eshkenazi said. Between 2014 and 2016 alone, enrollment in the top 25 supply chain programs ranked by Gartner jumped from 8,500 to 12,200.

Despite that growth until just a few years ago, “people had no idea what we did for a living,” Eshkenazi said. “I’d say ‘supply chain’ and they’d go ‘supply what?’ Now the awareness has just exploded”—a result not of the crisis, he said, but of the growing importance of supply chain experts even in a pre-pandemic world. And now, in the thick of the crisis, “companies can’t hire them fast enough,” Eshkenazi said.

At Penn State, Linderman sees this surge of interest as well. “Earlier we had to be active to get companies to come interact with our students, but now they’re knocking at our door.” Last year, Smeal measured the number of company-student interactions and interviews for each of its business degree specializations. “For supply chain, it was around 1,600. For each of the others, it was around 500.”

Saénz, the director of the MIT program, also noted a change in the kind of companies coming to recruit her students. Usually it’s established companies involved in manufacturing and production, she said, “like consumer goods firms, EV automotive manufacturers, and established tech firms.” Now, though, there are also numerous consulting firms and a host of start-ups that specialize in supply chain analytics. “They’re the kind that are doing intermediate supply chain work—consulting with companies to bring, say, an AI approach to some segments of their supply chain,” Saénz said.

In a wrinkle, though, many companies in 2021 suspended their practice of sending out their employees to be trained or to get a mid-career MBA in supply chain management, Eshkenazi said—presumably because they can’t afford to lose staff even temporarily during this supply chain crunch.

Fewer companies are paying for their employees to attend ASCM’s training modules, which last six to nine months, for instance. “People are coming to us directly, and those individual purchases have gone up because people know they need to be upskilled,” Eshkenazi said. “But I think we saw a hint of bad news in 2021 in that companies are cutting back on professional development when their financials aren’t meeting expectations.”

The omicron variant of covid-19 triggered fresh supply chain worries in early 2022. Even when both the pandemic and its logistics snarls pass—and they will, eventually—companies will have a new appreciation for the need to build more robust networks to source materials and ship products, Saénz said. “It’s like the supply chain has sent everyone a message, saying: ‘Guys, I’m important. If you forget me, if you don’t create resilience, this will happen again and you will suffer.’”