Chiquita is valued at $1 billion and WhatsApp 19 times that—the numbers that really prove Piketty wrong

Our times have an eerie similarity with the early decades of the 20th century—severe financial crises, a drastic skewing of income distribution, and terrorism (do not forget the assassinations of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, Empress Elizabeth of Austria, president Carnot of France, King Humbert of Italy, Premier Canovas of Spain, and president William McKinley of the United States.) Just recently, Vladimir Putin added a touch springing out of the 19th and early 20th centuries: the annexation of Crimea on patently invented pretexts. We only missed a Marx to warn us about a fatal flaw in capitalism to complete the picture.

Our times have an eerie similarity with the early decades of the 20th century—severe financial crises, a drastic skewing of income distribution, and terrorism (do not forget the assassinations of Tsar Alexander II of Russia, Empress Elizabeth of Austria, president Carnot of France, King Humbert of Italy, Premier Canovas of Spain, and president William McKinley of the United States.) Just recently, Vladimir Putin added a touch springing out of the 19th and early 20th centuries: the annexation of Crimea on patently invented pretexts. We only missed a Marx to warn us about a fatal flaw in capitalism to complete the picture.

In Thomas Piketty, we have found him. The French economist has written a bombshell best seller called Capital in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2014). In it, Piketty clarifies that he is not a Communist. Yet, he warns that capitalism will irremissibly lead us to a future in which an infinitesimal minority will own the entire capital in the world, or most of it. He thinks that this would be very bad and proposes solutions, which include an annual global progressive tax on capital that would go from 0.1% to 10% of its value, plus an 80% (yes, 80%) tax on annual incomes above $500,000. The benefit of these measures would not be better growth, less poverty, or a better quality of life, but, instead, the reduction of what Piketty considers an absolute bad (opposed to an absolute good): inequality.

That is, Piketty thinks that wealth should be redistributed, big time, to the point of almost total expropriation.

Last week, the Financial Times took the ground from below Piketty’s argumentations, showing that the main facts he was addressing with his theories and recommendations—that wealth was becoming more concentrated in the developed world—are not happening at all. In a long piece that goes into considerable detail, Chris Giles discovers that some of his data seems to have been wrongly typed, some other had been tweaked and wrongly manipulated, cherry picked, and just constructed out of thin air. When all is said and done, Giles found that the original sources Piketty alleged he had used did not support his assertion that the distribution of wealth is becoming more skewed. Rather, after having declined from 1910 to the mid-20th century, it has remained stable for the last 30 or 50 years (depending on the different Piketty’s original sources).

Well, for people who would like to believe that wealth should not be redistributed, this should not be a problem. After all, Marx’s arguments were proven false first by the power of logic and then by the power of reality through the terrible destinies of communist countries. Yet, many people remained Marxists even after it was clear that Marxism led to disasters, before and after the fall of the Soviet Union. Thus, the fact that Piketty’s data has proven faulty does not necessarily mean that people will abandon the ideas that drove him to write the book: that the distribution of wealth is too skewed, that this is bad, and that the problem should be addressed with a worldwide taxation aimed at redistributing wealth. Piketty’s ideas will keep on resonating, even if the reality he was supposedly addressing does not exist, primarily among them his urge to redistribute wealth in a wholesale way.

But, can wealth be redistributed in the 21st century in the rough and ready way Piketty is proposing? Could it be good to do it? We cannot answer these questions without answering a more fundamental one: What is the source of wealth?

Piketty does not provide an answer to this question, although he makes it clear that he does not believe that it comes from human capital—that is, the population’s level of education and health. In this respect, he makes a key mistake. He assumes that the value of human capital would be reflected in the income of labor—what a person is able to earn throughout her life. He writes, “Attributing a monetary value to the stock of human capital makes sense only in societies where it is actually possible to own other individuals fully and entirely—societies that at first sight have definitively ceased to exist.”

Piketty’s mistake is a very common one in socialists: They do not see that human capital is what gives life to physical capital and extracts wealth from it. Any non-socialist person will tell you that the value of a good piece of machinery is zero if you give it to someone who is not trained to handle it. A company with enormous assets can go bankrupt, losing its capital, if managed by incompetent people. That is the reason why just transferring all the machinery and enterprises of, say, Sweden, to an underdeveloped area of the world would not increase the wealth of the inhabitants of the latter to the level of the Swedish but rather would reduce the value of the capital to zero.

This has been true since human beings exist. Arrows and bows are useless if not properly used. However, it is becoming even truer in our times, as the share of pure knowledge in the creation of wealth is increasing dramatically in the 21st century.

Let’s apply economics to real life. In 2012, Facebook bought Instagram for a whopping $1 billion. The company, launched in 2010, happened to have 13 employees at the time it was sold. That comes to about $76 million per worker. Then in February, Facebook bought WhatsApp for $19 billion. The company, founded in 2009, had 55 employees. That makes for $345 million per worker. The purchasing company, Facebook, created in 2004, has a market value of $153 billion with 6,818 employees. That makes for $22 million per employee. Apple has $14 million per worker, Google $10 million.

Now compare this with Chiquita, the banana company founded in 1870, valued at $1 billion, with 20,000 employees in 70 countries. This makes for $50,000 per employee.

All the companies in the first group have a common feature: They have created solid value out of thin air and a good portion of their market value is the result of pure thinking—a product of human capital. The value of the conventional capital goods owned by Instagram and WhatsApp at the time of their sale (computers, desks, cement and bricks) was immaterial. What Facebook was purchasing was invisible software and access to the human capital that created it. Certainly, the people who created this invisible wealth earned very good salaries. But their creativity had a tremendous impact on the value of their companies—the capital, which is what Piketty was studying.

Instagram, WhatsApp, and even Facebook are relatively small companies. Is this happening also with the big ones?

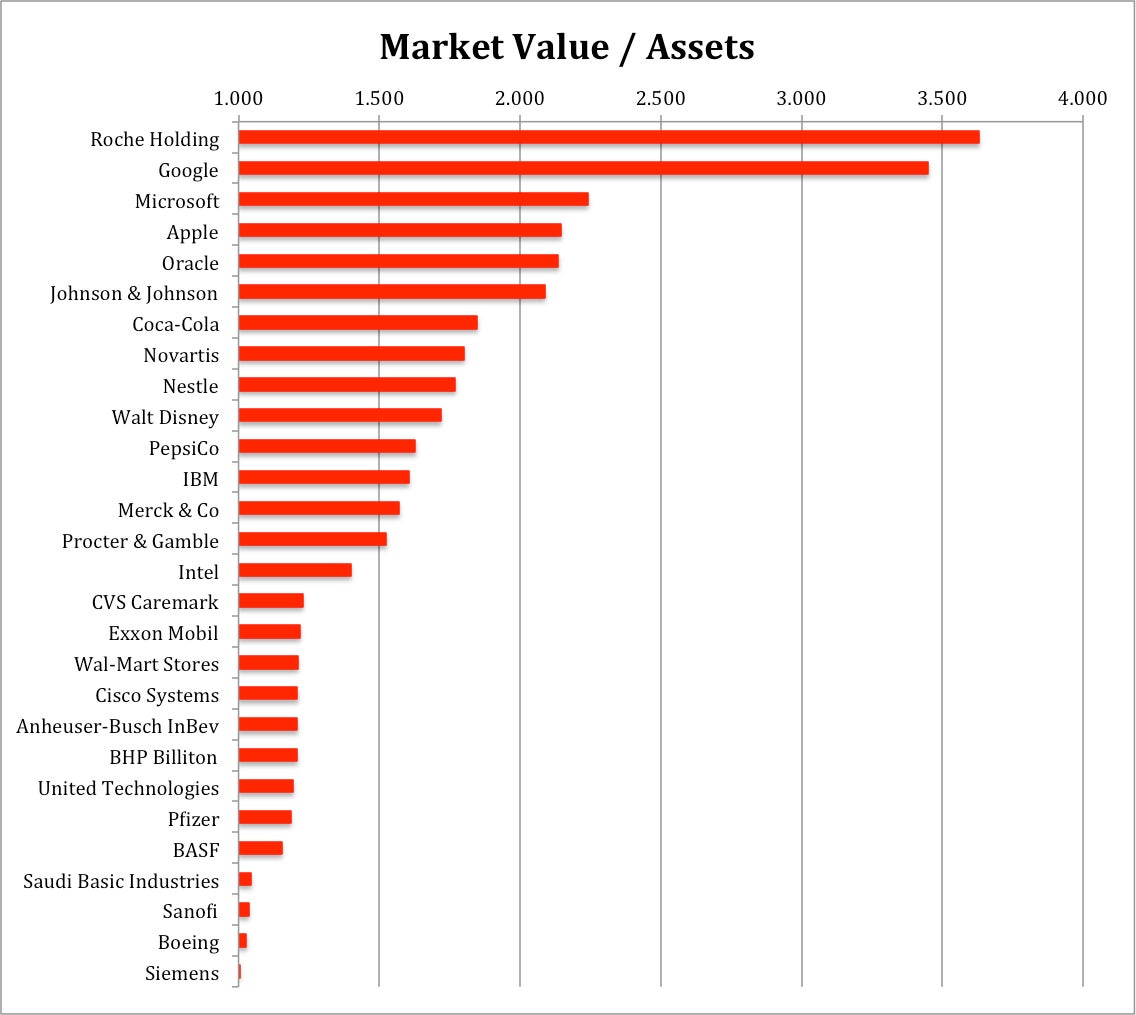

The 28 companies listed in the graph above have the highest ratio of market value to assets among the biggest 100 global public companies in the world. This phenomenon—people paying more than the value of a set of assets for shares that give them property rights over those assets—cannot be explained by anything else than human capital. People are paying for the collective genius that turns those assets highly productive. For example, investors pay for Google’s shares at 345% of the value of the company’s assets, 363% for Roche Holdings’.

Note that there are only two physical resource-based companies in the list—Exxon Mobil and BHP Billiton (mining)—and a few others delivering mainly physical products—Coca Cola, Nestle, PepsiCo, Procter & Gamble, CVS, Wal-Mart, Anheuser-Bush, Saudi Basic Industries, Boeing and Siemens. Most of the other 15 live out of their wits to produce invisible products almost exclusively—formulas in the pharmaceutical business, software and designs in the information technology and stories in the entertainment industries. But even the resource-based and the conventional companies in the second group have a higher market value to assets ratio because of the fruits of human capital—patents, well-established brands, and similar advantages. Nobody can say, for example, that anyone can manage Boeing and design, build, and sell its planes.

Chiquita is not in the list, but its ratio of market value to book value is 1.0. This does not mean that Chiquita does not require human capital to be managed properly, only that it is not especially higher than what is easily available in the market.

Of course, the conventional companies, those that owe their value to both physical and human capital, are still fundamental in the global economy. Yet, as time goes by, the importance of human capital is increasing. Knowledge and the ability to coordinate complex tasks at a distance are essential to take advantage of globalization. These abilities will shape capital in the 21st century. The importance of this can be appreciated in the fact that, in terms of assets, Apple ranks 57th among the biggest 100, while in terms of market value it is first.

In his analysis, Piketty missed this crucial dimension of capital and its multiple implications. One of these is that you cannot expropriate this new kind of capital, which will be predominant in the 21st century. How much life has changed since Marx’s good old days! There was a time when the dream of the Central American (and actually Latin American) socialists was to expropriate Chiquita to get hold of the banana plantations, the banana ships, the machinery, the houses of the engineers, which they thought were the source of the wealth of the United States. Of course, even at that time, the wealth of the company was not in those things but in its managers’ capacity to operate those assets efficiently. Fidel Castro, for example, expropriated all companies in Cuba and then ran them aground, reducing to zero the value of their capital.

But now Chiquita is no more a symbol of wealth because human capital is only a small part of its value. In this new world, it does not make sense to try to do what the far left wanted to do in Marx’s and Lenin’s days. Wealth is now in things that cannot be expropriated: software, thoughts, education.

Rather, it would be more helpful to invest more effectively in spreading human capital development. That would really spread wealth and income more evenly throughout societies, as it happened during the 20th century when the benefits of industrialization spread to all social classes in the industrialized countries as a result of better education and health.